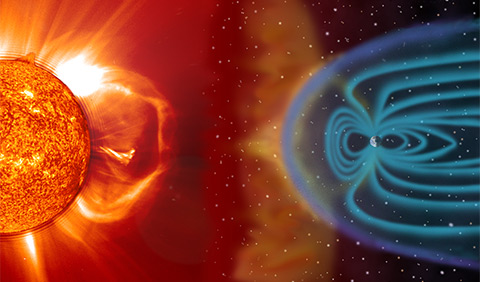

Illustration showing blasts of particles and magnetic field from the Sun that impact the magnetosphere, the magnetic bubble around the Earth (courtesy NASA).

Outbursts observed on the sun last week do not portend new problems for GPS reception or other systems as solar flares and eruptive events known as coronal mass ejections fire up during an increasingly active phase, said a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration space weather expert.

Widespread reports of last week’s solar activity, following a very tranquil period, may have created an impression that solar storms were unusually powerful, the expert said. Magnetic fields on the sun’s surface have intensified, showing up as increased sunspots and generating eruptive activity as a quiet portion of a well-known 11-year sunspot cycle ends.

“We have come out of such a quiet period that it’s pretty interesting from that point of view,” said Joseph Kunches, a space weather scientist for NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center. “The last outbreak was back in 2006. The sun has been pretty dormant.”

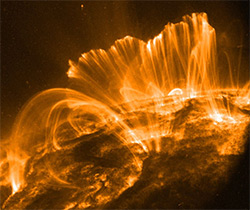

A ball of hot gas, the sun does not rotate as a rigid body. Turbulent effects of that uneven rotation can produce explosive results on the surface, Kunches said.

The recently noted outbursts featured a coronal mass ejection measured at Level 3 on a 1 to 5 scale for solar storms. Putting that in context, Level 3 events occur approximately 200 times during the 11-year cycle, with most outbursts clustered near the cycle’s peak, Kunches said.

Although a solar flare’s “lightning-bolt-like quick indication” can be the earliest evidence of a sudden release of energy on the sun, Kunches said, a more subtle development scientists monitor is whether a portion of the sun’s outer mass--its corona--has been blown off into space.

Such coronal mass ejections are “very directional,” sending a cloud of charged particles hurtling away from the sun. When a coronal mass ejection is observed “right in the middle of the sun,” watch for a plasma cloud to head for the earth, taking between 30 and 72 hours to arrive.

Such coronal mass ejections are “very directional,” sending a cloud of charged particles hurtling away from the sun. When a coronal mass ejection is observed “right in the middle of the sun,” watch for a plasma cloud to head for the earth, taking between 30 and 72 hours to arrive.

“Last week we had three eruptions from the center,” he said. “Some time later we felt the effects of those plasma fields that disturbed and energized the earth’s magnetic field.” Spaceweather.com reported that an Aug. 9 flare emanating from sunspot 1263 was followed by brief disruption of communications “at some VLF and HF radio frequencies.”

The potential for GPS interference exists because atmospheric noise generated by a coronal mass ejection can drown out the GPS signal, which may be unable to “punch through this mush of electrons.” Or, a GPS unit may seem to be working properly, but its indications are off by up to 50 meters, Kunches said. He consults this real-time map to monitor electron activity in the atmosphere.

Perhaps it was a combination of the solar cycle and the news cycle that generated the interest in solar activity, which, he said, “just wasn’t that big a deal last week.”

On Aug. 10, the Space Weather Prediction Center’s three-day report of solar and geophysical activity reported high solar activity for Aug. 8 and 9, but predicted low to moderate activity for the following three days as an active area rotated around the sun’s west limb.