Craftsmanship: Where Wacos take wing

People all over the world seek out these father-and-son biplane restorers

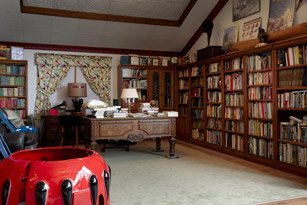

There’s nothing about the two-story brick building in the small central Pennsylvania town of Emigsville to suggest that the two master craftsmen inside create some of the world’s finest vintage biplanes.

For nearly 30 years, the father-and-son team of John and Scott Shue has quietly turned out Waco biplanes of exceptional quality using the same old-world techniques as the original builders in the 1930s.

John restored his first Waco, a tattered World War II-era UPF–7 trainer, in the mid-1960s and then-5-year-old Scott assisted with menial tasks such as scrubbing the bare fuselage tubing with a wire brush. Since then, the two have re-created many flying works of art, including nine that have won top awards at prestigious competitions such as EAA AirVenture in Oshkosh.

Dumb luck

John spent most of his career as a manager at a national electronics firm, and he flew general aviation aircraft and restored them for personal enjoyment. The first biplane he purchased was in 1964. He was driving near State College, Pennsylvania, and asked a few local pilots if they knew of any biplanes that were in disrepair or long-term storage. He found out about a former pilot who had a half-dozen dilapidated airframes inside a nearby barn and sought him out. That’s where John discovered NC30165, a former World War II pilot trainer that had fallen into disuse. “I didn’t really know what I was looking for at the time,” John said. “I knew I wanted a biplane with a headrest and a bump cowl like the ones I grew up reading about in pulp books. This one seemed to fit the bill.”

John spent most of his career as a manager at a national electronics firm, and he flew general aviation aircraft and restored them for personal enjoyment. The first biplane he purchased was in 1964. He was driving near State College, Pennsylvania, and asked a few local pilots if they knew of any biplanes that were in disrepair or long-term storage. He found out about a former pilot who had a half-dozen dilapidated airframes inside a nearby barn and sought him out. That’s where John discovered NC30165, a former World War II pilot trainer that had fallen into disuse. “I didn’t really know what I was looking for at the time,” John said. “I knew I wanted a biplane with a headrest and a bump cowl like the ones I grew up reading about in pulp books. This one seemed to fit the bill.”

John paid $600 (about $4,530 adjusted for inflation) for the airplane and arranged to tow it away. It also came with a metal propeller, a rare Curtiss Reed model with a current value of more than $12,000. “That was just dumb luck,” he remembers. “I had no idea what I was getting.”

The Shues painstakingly restored the UPF–7 into a showpiece. The airplane helped create an enduring demand for a model that had long been dismissed as unremarkable, low-budget trainers that had outlived their usefulness. “In those days, no one thought restoring an old, torn-up UPF–7 with drooping wings made economic sense,” John said. “When people saw that a UPF could be a showplane, it changed a lot of minds.”

The Shues have made a habit of buying surplus parts wherever and whenever they found them. “When I find Waco parts, I buy them,” John says. “I think I’ve got at least one of just about everything the company ever made.” The Shues used to sell surplus parts, but now some parts in their 50-year-old inventory are so rare, the parts are too valuable for their own use to let go.

Still, even with all their experience and resources, the Shues get stymied. One of the Wacos in their shop, a 1935 UMF model, originally was built with a rare pneumatic starter for the radial engine. The Shues have scoured the Internet seeking to unearth a similar starter, but so far without success. “The owner really wants an original pneumatic starter, and I thought it was a great idea,” John said. “But I’m about to throw up my hands on this. We’ve tried everything we can think of and had no luck at all.”

An artist

The final piece of any Shue restoration is bringing the airplane to York Airport (THV) for final assembly and a return to flight, and John and Scott use their own methods for this, too. They hook the tailwheel to a pickup truck and drive a dozen miles to the airport, usually at odd hours and on back roads where traffic is light. It’s a simple system, but there can be complications. “We got pulled over one time and the officer measured the tail and said it was two inches too wide to transport on the road,” Scott said. “He was going to make us take the tail off, and we really didn’t want to do that.”

The tail surfaces had already been meticulously rigged, and disassembling them on the side of the road would set them back weeks. Then a friend who was helping with the move suggested an “agricultural exemption.” The biplane was once a crop duster, he said, and that made it eligible to be treated as farm equipment—which allows for wider loads. They finished the trip to the airport with the airplane intact.

As for the post-restoration flights, they usually are anticlimactic. Each airplane has been fully assembled and rigged at least twice before it ever gets to the airport. (The first rigging takes place before the airplane is covered, and the same process is repeated after painting.)

“We might make a few minor tweaks after first few flights but we never need to do anything major,” Scott said. “The center-section wires are the most important part of any biplane and we spend a lot of time on them. If you get that right, the airplane will almost always fly right.”

The Shues have rented a hangar at the airport for more than a half-century, but they insist on doing restorations at their off-airport shop. They say it’s more cost-effective for them to stay at a place that’s already paid for, and with few distractions. They say moving to an airport would increase restoration costs, and have no desire to go anywhere else.

A local group of pilots and restorers comes by the shop once a week to share stories and go to a local diner for lunch. No one minds when Scott has classic rock on the radio, and he doesn’t have to ask permission to bring his yellow Labrador retriever to the shop.

The Shues have several personal projects they would like to take on, including an original Curtiss Jenny biplane. But they estimate their current backlog at five years, so they aren’t sure when, or if, they will get to it.

The father and son have seldom been apart more than two weeks since Scott was born, and their respect and affection for each other is obvious. “Scott’s a far better woodworker than I ever was,” John says. “He’s an artist. He’s so meticulous it’s unbelievable.”

Scott shrugs off the compliment. “He’s just as meticulous as I am,” Scott says of his dad. “All my work habits come from him.”

Video: Spend a day in the workshop with John and Scott Shue.

Photography by Mike Fizer

Email [email protected]

“I love woodwork, and it’s the part of every aircraft restoration that I enjoy most,” says Scott, 54, whose Harley-Davidson T-shirt and faded jeans reveal a passion for motorcycles. “I know I could take shortcuts and use staples instead of nails in the wing ribs. But there’s a challenge in doing things right—and I get a lot of satisfaction in knowing that everything on our airplanes is done as original—even if they’re deep inside the airframe in places no one else can see.”

Scott puts a final coat of varnish on a set of Waco wings he’s about to complete, and the wood glistens in shafts of morning sunlight that shoot in through the shop’s high windows. The wood spars are Sitka spruce from coastal Alaska and the wing tips are mahogany plywood, just like the originals.

John, an A&P mechanic with inspection authorization, started rebuilding airplanes with his father and brother Charlie in the mid-1950s. John prefers Wacos because of the high quality of the original design and construction, and he’s stayed with them because they are what he knows best—and “I prefer to stick to what I know.”

The Shues cover and paint their restorations using labor-intensive techniques that create lustrous colors and textures. It took 39 coats of butyrate dope, for example, to get the creamy, sky-blue finish they wanted on one of their current projects. The Shues’ way takes more patience and skill than other methods—but they know their airplanes will stand up over time.

In fact, the first Waco they restored almost 50 years ago, NC30165, is now in their shop being re-covered—even though the airplane looked more than adequate when it came in. “That’s the airplane that Scott soloed in, and we treated it like part of the family,” John says. “We flew it all over the country, camping under the wings. It won lots of prizes, too. We’ve got a lot of family history in it.”

Scott said the real reason they are restoring NC30165 is that John is considering selling it. “He won’t be able to let it go until it’s perfect,” the son says.

The Shues began overhauling NC30165 two years ago, and the fuselage and center section are complete and painted a resplendent red. The project is on a back burner, however, because it’s their own airplane—and customer projects take priority.

“You know the story of the cobbler’s son being the last to get new shoes,” John says. “The same thing happens here.”

Pilots find breathtaking beauty in the curve of a propeller, the shape of a wing, even the thoughtful interface of a piece of avionics. But who makes this stuff and, in some cases, keeps it beautiful for decades? Our new occasional Craftsmanship series explores the people who create—and re-create—these things for us. —Tom Haines

“Scott was a little kid when we restored our first Waco, but he was helpful all the way through,” says John, 82, who later taught his son to fly in that airplane and watched him solo it on his sixteenth birthday—a snowy February morning in 1975. “He’s been helping me ever since, and now he’s surpassed me. Scott’s a master woodworker and people all over the world come to him when they want wings.”

The father and son have worked side by side so long, they can anticipate and deflect each other’s barbs. When John teases his son for being “so damn finicky” about his work, Scott’s pat response is a disarming smile.

“I learned it all from you, Dad.”

The two share an outlook on their craft, and their business: Aircraft by Shue. They work at a steady and deliberate pace, and they have no inclination whatsoever to expand their output. They tell aircraft owners that a complete airframe restoration takes about three years—sometimes more, and sometimes less—and a new set of wings takes six months. When a restored aircraft leaves their facility, it must be perfect in every detail. As a testament to their pride and confidence in their work, the father and son make post-restoration test flights together.

The Shues have hired full- and part-time employees in the past, and they’ve pressed Scott’s sister Tracy into the family business at times. But they prefer doing as much as possible themselves—and these days, that means pretty much everything.