Rotorcraft Rookie: Time to go somewhere

Long cross-country in a helicopter

Among the few requirements to get an add-on helicopter rating is three hours of dual cross-country training. Having already done this to earn a private and commercial fixed-wing certificate, this seemed a bit overkill. Leading up to the flight I was more focused on what I assumed was a waste of money than the learning opportunity. But it turned out to be a great learning opportunity. Going cross-country in a helicopter is different for three main reasons—the speed and available equipment in the helicopter, the flight controls, and altitude.

Helicopters are generally slower than comparably powered airplanes, and the Robinson R22 is no exception. We flight planned for 75 knots. With a 30-knot headwind on the first leg of the trip, that made for some slow progress. It also explains why picking checkpoints every five miles makes sense. In an airplane that would make for a lot of work every two minutes. But in the helicopter that’s a solid five minutes or more to consider the chart and mentally recalculate the time to the next checkpoint.

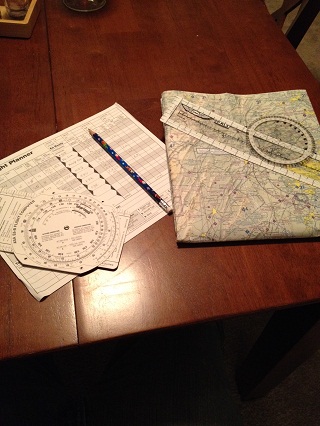

I’m lucky enough to have a few dozen hours in a Piper J-3 Cub before the iPad age, so I’ve spent lots of time with a chart and a watch. That’s pretty much exactly what life is like in the helicopter as well. Bigger and more expensive machines have GPS, but the flight school’s aircraft have no electronic navigation. It’s the window, a compass, a chart, your plan, and a watch that gets you from point A to point B. That may seem positively ancient to some, but I love the nerdy challenge of staying on a course solely by looking out the window and verifying on the compass.

Logbook

Total time: 14.8 hours

Maneuvers: Long cross-country

One big difference between flying in the airplane and the helicopter is recalculating the checkpoint time en route. In an airplane I would expect a student to have one hand on the yoke and the other on the E6B trying to determine the time to the next point and how that would impact the fuel situation. In the helicopter you run out of hands. You can let go of the collective for a second or two, but not long enough to recalculate the checkpoint times. So instead we estimated the times and changed the airspeed to try and match the plan.

Two-handed flying also causes a bit of a dilemma with cockpit management. It’s even more important to have everything tidy and ready to go prior to taking off. Refolding charts and shuffling flight plans becomes pretty tricky with only two hands when both are needed for the flight controls. The same goes for changing radio frequencies. In that sense not having a GPS or moving map to constantly manipulate is a gift.

One thing that’s generally easier in the helicopter is fuel planning. It’s always nine gallons an hour, partially because Robinson recommends not leaning for normal operations. That’s likely because most of the time the helicopter never goes above a few thousand feet. In fact, I had flight planned for about 2,500 feet agl and my instructor Otto said it was a bit high. “We’re in airplane territory up here,” he joked. He has a point. By staying lower there’s less of a chance for a traffic conflict. So we spent most of the flight between about 1,000 and 2,000 feet agl.

The next scheduled flight is a required night cross-country, something I’ve never done without electronic navigation aids. I guess it will be time to see if a full-size iPad will fit in the cockpit.

Next time: Night flight

Read all the stories in the Rotorcraft Rookie series.