Here they come, like clockwork

Like it or not, winter’s here. But that doesn’t mean we have to helplessly await the coming onslaught of rotten winter flying weather. Thanks to the climatological record of the past 30 years, we can rest assured of the nature, locations, and travel patterns of the storms, fronts, and other mayhem to come in the months ahead.

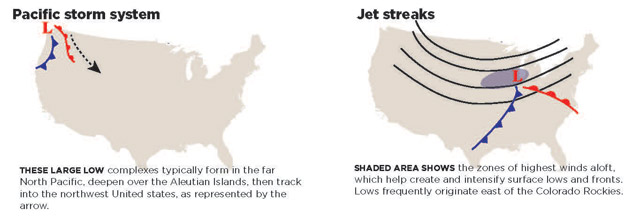

Pacific storm systems. One rule of thumb holds that most adverse winter weather systems enter the United States in the Pacific Northwest. Deep low pressure complexes in the North Pacific ride a conveyor belt of high-altitude jet stream winds on their way to Alaska, Washington, Oregon, and California. To see them coming, your best bet is the Aviation Digital Data Service’s prog chart online or satellite imagery for the telltale counterclockwise cloud formations that signal well-organized low pressure circulations. The ADDS satellite page does a good job as well.

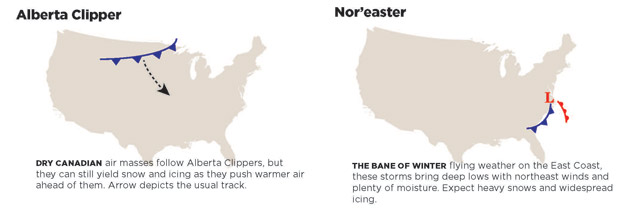

Alberta Clippers. As the name suggest, these fast-moving fronts originate in or near the western Canadian province of the same name. They tend to produce more turbulence and high surface winds than dense clouds and snow, but icing still can be a factor. As they travel in a southeasterly direction, clippers can affect the central and eastern United States until warmer temperatures and competing weather systems take the fight out of them.

Jet streams and troughs aloft. If you’re someone who leans on shorter-term 36- to 48-hour surface analysis and prog charts for future synoptic situations, you may miss a big warning flag—deep troughs aloft. These U-shaped patterns can easily be identified on the 500-millibar (about 18,000 feet) and 300-millibar (about 30,000 feet) constant pressure charts. The fastest jet stream winds are most often found in the areas east of a trough’s apex, where the height contours (lines depicting heights of equal pressure surfaces) are most compressed. Like isobars on surface analysis charts, tightly-spaced height contours indicate the strongest winds aloft. Bands of the strongest (50 to 150 knots or more) winds impart lifting forces to the air below—and if that air is cold and moist enough, you can expect major-league winter weather. This includes deep low pressure systems with both cold and warm fronts, each containing plenty of snow, icing conditions, low ceilings, and low visibilities.

Winter warm fronts. Does the mention of warm fronts make you think of balmy temperatures? Forget that. Winter warm fronts are associated with some of the worst icing conditions. Warmer air riding up over colder air below can create layers where temperatures can run between plus 2 and minus 10 degrees Celsius—right where clear and mixed icing conditions prevail. And any above-freezing precipitation falling from a warm frontal surface into subfreezing air beneath it can produce freezing rain—even if that colder air consists of good visual meteorological conditions! Worst of all, warm frontal weather can be spread over several states, creating not just icing conditions but plenty of instrument weather. If you miss an instrument approach, a suitable alternate may be a long way away, and the weather en route could be a challenge, to say the least.

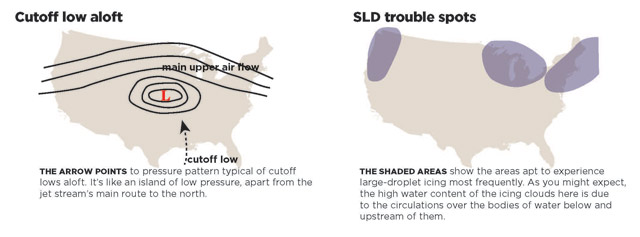

Trouble spots. Large-droplet icing conditions have caused a number of high-profile fatal accidents. Rime ice is created by the smallest supercooled droplets and colder (say, minus 10 to minus 20 degrees Celsius) temperatures. Clear ice is a product of larger droplets and warmer (minus 10 to plus 2 degrees Celsius) temperatures. But other types of clear icing—large-droplet icing, as well as freezing drizzle—consist of the largest droplets and highest liquid water contents of all (each one about the size of a raindrop). When these droplets strike a leading edge, they run far back along the wings and other airframe parts before freezing. This runback ruins lift even more severely—and quickly—than “ordinary” clear ice. Not surprisingly, these conditions prevail most often near the Great Lakes, the Pacific Northwest, and the coastal New England states—areas already heavily saturated by the moisture from their associated large bodies of water.

Nor’easters. Every winter several coastal storm complexes make their way up the eastern seaboard, some of them reaching farther inland than others. Strong winds out of the northeast announce their arrival, hence the name. Depending on the locations of their lows and fronts (inland storm tracks are worst), nor’easters can draw in enough cold air to produce widespread icing conditions and instrument weather. And with their origins and tracks over the Atlantic Ocean, all that moisture can mean rain, snow, ice pellets, freezing rain—or all four. Sometimes, lots of it.

Cutoff lows aloft. By far, the longest-lasting adverse winter weather is caused by closed lows aloft. These can be identified on 500-millibar constant pressure charts as islands of low pressure lurking south of the main upper-air wind flows. However, their closed circulations can extend from the surface all the way to the tropopause, which in meteorology-speak is called vertical stacking. Because they are detached from the upper winds, closed lows don’t move with them. So they remain stationary for days, covering thousands of square miles with instrument meteorological conditions in rain, snow, or ice—depending on the vertical temperature profile. And things won’t change until the next trough aloft comes along and shoves it downwind. Some use the term “closed low aloft” interchangeably with “cutoff low,” but there is a difference. Cutoff lows are truly separate from the upper-air flows to their north. Closed lows exist within an upper trough. Either way, these closed circulations mean you’ll be filing IFR flight plans for the duration. To make things worse, cutoff lows are unpredictable in their movement. Sometimes they even move westward!

Do you need a flight service weather briefer to warn you of these winter systems? Yes and no. There’s no substitute for a good, official weather briefing, but there’s nothing to prevent you from doing some of your own probing on the many weather websites that depict both general and aviation weather.

Email [email protected]