The TFR in the 72-page briefing

It was a flight I had done a number of times before: Fly a friend and his daughter to Purdue University; stop in Lansing, Illinois, for business; and fly home. I got my DUATS briefing through my electronic flight bag flight planning program—72 pages, including some presidential TFRs in Chicago.

I hand-plotted the TFRs and noted two concentric rings with the same times and altitudes but different radii. Odd. But all the TFRs were north of Lansing, so I gave it no further thought.

I launched from Hagerstown, Maryland, the next morning for Purdue University Airport (LAF). There were stiff headwinds at 10,000 feet. At least I would have some nice tailwinds for the trip home. My friend and I got his daughter to her dorm and grabbed a bite to eat on the way back to the airport. The EFB showed all clear for the flight to Lansing. It would be a short flight, so I opted to go VFR.

The Lafayette tower cleared me to depart VFR, and I switched over to Chicago to pick up flight following. The controller was just slammed with Chicago traffic, so I never could get in a flight following request. Fortunately the EFB with Stratus was picking up all the great ADS-B In information. The current METAR at Lansing Municipal Airport (IGQ) was good; no convective activity; and the TFRs all were north of IGQ. I still felt a bit naked not being “in the system.”

I steered to the straight-in to Runway 36. The ATIS matched the FIS-B METAR. I made calls on the common traffic advisory frequency at 20, 15, 10, and five miles out. I was on short final, gear down, full flaps, and right on my target airspeed. Without warning, the Baron abruptly yawed 15 degrees right, and there was a thunderous noise on the right side of the aircraft. I was standing on the rudder pedals to maintain directional control and managed to keep things more or less aimed at the runway.

It was quickly apparent that the problem was not the right engine. I starting thinking I had lost the utility doors on the right side of the cabin, but they were fine. Everything returned to normal within a few seconds, and the noise was abating. The adrenaline was still pumping when I barked to my friend, “What the—was that?” I did not have time to wait for a response as I was already beginning to round out for landing. As we touched down, my friend, an Air Force officer, responded, “It looks like an F–16.”

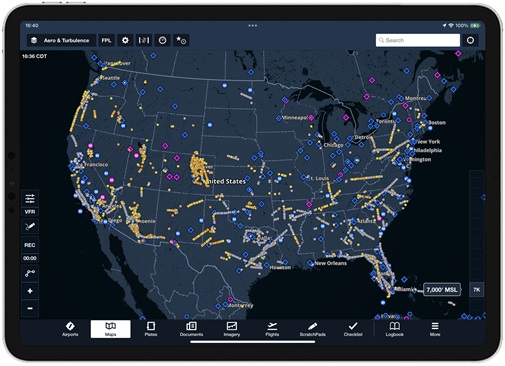

On the rollout I got a look at the F–16 in full afterburner climbing back to altitude and turning to circle the field. I concluded immediately that we had been “thumped,” a procedure we used in the military that was designed to rattle and harass the pilot of an intercepted aircraft. I asked the FBO on the CTAF if there was a TFR over the field and got an affirmative response. I remember checking my iPad (and later took a picture). Go figure, the ADS-B display was still showing all the TFR rings north of IGQ.

After further reflection I realized my mistake that day in August 2012 was not taking a closer look at those odd concentric TFR rings when I reviewed my DUATS briefing. It turned out that the first line of the description of that first ring was at the end of part one of that six-part FDC notam. I started at the beginning of part two without realizing I was actually joining the second line of the first TFR ring and the first line of the second TFR ring, and so on. I actually had to re-plot the rings a couple of times after the incident before I finally figured out what had tripped me up.

I also got firsthand experience with the FAA’s enforcement process. Over the next 18 months, my lawyer and I discovered a number of startling facts. Regarding the ADS-B TFR display on my iPad, the FAA admitted the ADS-B broadcast was “incomplete.” The FAA regional administrator wrote that “the FAA attempts to issue a graphical depiction of restricted airspace for the convenience of pilots, the FAA is not required to do so, and the absence of a graphical depiction does not render a published flight restriction invalid.” My use of the EFB to obtain my DUATS briefing was also ruled a violation of FAR 91.103(a) because it was “not an FAA-approved source of preflight and safety of flight information.” Apparently the FAA’s QICP certification of the “reliability, accessibility, and security” of the EFB’s network infrastructure somehow did not apply to retrieving and delivering the FAA-approved DUATS briefings.

My pilot certificate was suspended for 30 days. I had filed a timely NASA Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) report. Yet the FAA’s attorney insisted the agency would not communicate its reasons for rejecting the waiver of penalty afforded by the ASRS program. My letters to the FAA administrator and formal fraud, waste, and abuse complaints were ignored. My lawyer and I concluded that appealing the matter would have cost considerably more. We also did not believe we would get a different ruling, given the case history and the fact that appeals almost never overturn an FAA finding.

The lesson I learned the hard way that day is that the multibillion-dollar ADS-B capability, according to the FAA regional administrator, “is not to be used for real-time navigation, that it is only advisory, and that pilots should contact air traffic control or a FAA Flight Service Station that provides weather and other safety information.” Think about that the next time you rely on ADS-B information. I wished I actually had received a traffic alert before that F–16 almost caused me to lose control of my aircraft.

Mike Mercer, of Vienna, Virginia, is an instrument-rated pilot with commercial and single and multiengine land and sea ratings. He is a former Air Force officer.

Illustration by James Carey

Digital Extra: Hear this and other original “Never Again” stories as podcasts every month on iTunes and download audio files free.