Jeff Gorman just bought a King Air—his sixth consecutive King Air, to be precise. But this latest model, a 1996 C90B, isn’t just any old C90. It’s a one-of-a-kind upgrade/restoration project that will offer his firm, the Gorman-Rupp Company of Mansfield, Ohio, yet another means of business transportation over shorter routes. Gorman-Rupp, which makes some 4,000 different types of industrial, municipal, agricultural, flood control, refueling, and other heavy-duty pumps, has 12 manufacturing sites and branch offices across the United States and Canada. For reaching the most-distant locations, such as ones in Phoenix and Lubbock, Texas, Gorman uses the company’s recently purchased Lear 75.

The C90B will be used to go to plants closer to Mansfield, such as the one at St. Thomas, Ontario. “It’s a nine-hour drive by car, but in the King Air I can get there in 40 minutes,” Gorman said. Most of Gorman-Rupp’s trips involve bringing prospective customers to visit the Mansfield plant—and cultivating new business.

That’s become a tradition in this family operated, publicly owned company. Back during the Korean War, the U.S. Air Force needed to replace its refueling pumps with newer, higher-flow units. Jim Gorman, Jeff’s father, flew to meet Air Force procurement officials at Dayton’s Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in the company’s Model 35 Bonanza. An order for $850,000 in Gorman-Rupp pumps quickly ensued. “That was a lot of money in those days,” Jim commented. On the way out the door, he passed the competition on its way in. They had driven to Dayton, and their tardiness cost them the sale.

Making a winner

The Gormans always favored Beechcraft products, so a C90 always made sense as a choice for a short-haul airplane. Why not buy a new C90GTx? you might ask. For one, the airplane’s $3.89 million (base) price tag. For another, the airplane’s Rockwell Collins Pro Line 21 avionics.

“I grew to really appreciate the Garmin G1000 after we became familiar with the Lear 75’s G5000 avionics,” Jeff Gorman said. “I like the big screens, situational awareness, and lower workload of the G5000, so I decided I’d buy a good used C90 and upgrade it with a G1000—which is what I consider the state of the art in avionics.” List price of a C90B’s G1000 retrofit is approximately $350,000, which includes the price of an installation taking 1,200 hours and one month.

A low-time 1996 C90B was located in nearby Detroit and Gorman bought it at “market price,” which is about $1.1 million to $1.5 million according to aircraft evaluator Vref. The airplane had just 2,700 hours total time, and its original 550-shaft-horsepower Pratt & Whitney PT6A-21 engines still had 900 hours to go until their 3,600-hour recommended times between overhaul (TBOs).

Gorman’s flight department took the airplane up for an acceptance flight and the deal was done. After that, it was a one-hour flight to the Stevens Aviation Inc. facility at Dayton International Airport, where it underwent its transformation. And it wouldn’t just involve a G1000 upgrade.

To secure a 30- to 40-knot speed advantage, Gorman decided to swap out the original -21 engines for a pair of Blackhawk Modifications’ Pratt & Whitney PT6A-135 engines of 750 shaft horsepower, flat-rated to the stock airplane’s 550-shaft-horsepower power rating.

Part of this mod—which lists for $667,000—involved a $60-per-hour credit for the unused hours to TBO, which would defray costs to the tune of $108,000.

In terms of performance, Blackhawk’s flat-rating of the 750-shaft-horsepower engines meant that the airplane would be able to put out the full 550 shaft horsepower up to 19,000 to 20,000 feet; the stock -21 engines would begin losing torque and power at approximately 13,000 to 14,000 feet.

Bottom line: the Blackhawk engines would give Gorman’s C90B a maximum cruise as fast as 270 knots in the 23,000- to 24,000-foot-altitude range. The stock airplane would be limited to approximately 235 knots.

For an average 20-percent reduction in takeoff ground run, Gorman went with Raisbeck Engineering’s popular 90-Series Epic package. This includes Hartzell Propellers’ swept four-blade propellers of 96 inches in diameter (stock props have 90-inch diameters). The swept design and extra diameter provide more thrust, while the swept blades keep noise down—and they look good on the ramp, too.

Owing to the extra thrust, VMC rises to 92 KIAS, up from the standard airplane’s 87 knots. Gorman also added Raisbeck’s Crown wing lockers and dual aft body strakes to the list of improvements. The list price of all the installed Raisbeck mods is $149,395.

BLR Aerospace’s winglets ($63,200) also were added to the mix. These reduce induced drag and provide a slight boost in speed, according to the company. The winglet structure adds three feet, five inches to the wingspan, so extended-length deice boots were installed. These not only add ice protection to the entire wingspan, but fill in what would have been an awkward-looking foreshortening of the boot had they not been applied.

Finally, a cluster of three of Lopresti Aviation’s high-intensity-discharge (HID) “Boom Beam” landing lights ($8,990) were installed on the C90B’s nosewheel assembly.

Oh, and a new interior, including soundproofing blankets, plus new windshields and windows—and a new paint scheme, which matches that of Gorman-Rupp’s Lear 75—rounded out the upgrade effort.

Time and effort

Stevens Aviation Inc.’s Dayton facility has been maintaining Gorman’s personal airplanes, and Gorman-Rupp’s corporate airplanes, since 1967. Owing to that, you can tell there’s an extra measure of trust and even friendship between the service staff, which is headed up by service manager Mick Waltz, and Jeff and Jim Gorman. After all, we’re talking about a total of nine airplanes over the years: a Beech Queen Air, two Beech 200s, a Beech B200, two Beech King Air 350s, plus the Gormans own Bonanza V35B, Beech Duke (the last Duke built, by the way, which was recently donated to the Beechcraft Heritage Museum in Tullahoma, Tennessee), and a Piper Super Cub.

Stevens-Dayton also made sense because it had done Blackhawk conversions before, and the facility is Raisbeck Engineering’s seventh top installer in the world. And let’s not forget one more big factor working in Stevens-Dayton’s favor: In Ohio, there is no sales tax on labor or parts.

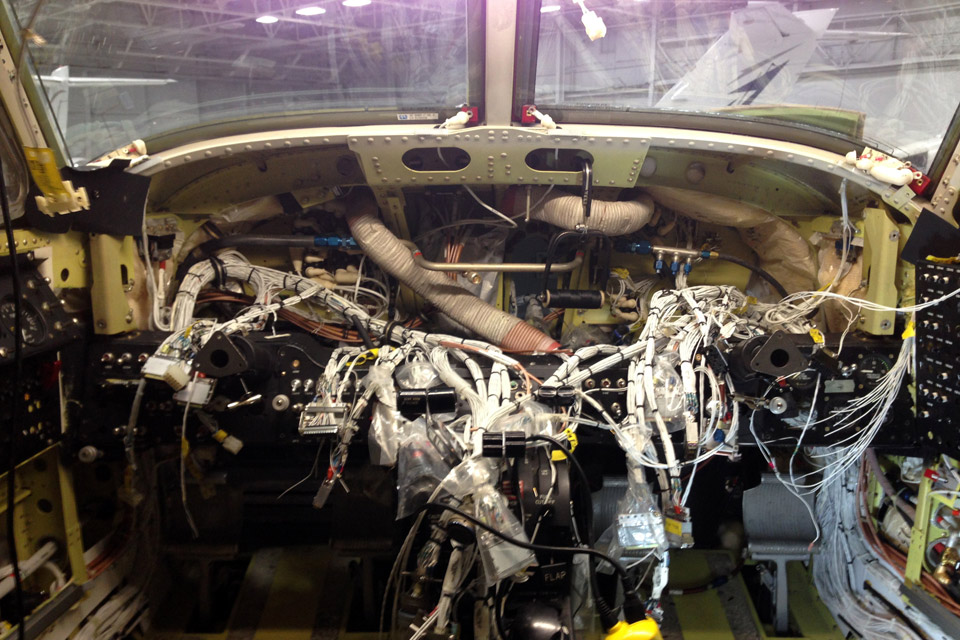

Stevens began work on the Gorman-Rupp C90B in November 2014, and finished up in February 2015. Not counting the G1000 and the paint and interior work, labor for the project ran $56,020 according to Waltz. The G1000 work, led by avionics manager Austin Teel, was the biggest bear in the work package. My hat’s off to anyone who can deal with the sight of a full-blown panel installation in progress. For those who haven’t seen one, think of an explosion in a spaghetti factory.

I wasn’t provided the details of the actual billing, but if you add up the list prices of all the work Stevens-Dayton performed you’d come up with a number somewhere around $1.3 million, not counting paint and interior. Add that to the, say, $1.1 million that Gorman paid for the airplane—and, yes, the upgrade wasn’t cheap.

“But it’s better than new,” Jeff said. And the total cost still comes in roughly $2 million less than a new C90GTx. All for an airplane that’s faster, uses less runway, has the latest panel innovations—and looks sexy, too.

Email [email protected]

Gorman-ology

The Gorman family is as aviation-minded as you can get. Jim Gorman, son of the founder of Gorman-Rupp, had his first airplane ride in a Ford Tri-Motor in the late 1930s. He flew C–47s (DC–3s, in civilian parlance) in the South Pacific in World War II, bought his first Bonanza in the late 1940s, and a 1946 Beech Staggerwing in 1967. His wife Marge flies. Jeff, his son, flies. Jeff and his wife have a private airstrip on their home property in Mansfield, Ohio, where they keep a 1976 V35B Bonanza, a Super Cub—and the Staggerwing his dad bought. The Gorman-Rupp Company has always had a flight department, and today it employs three full-time pilots.

As for Gorman-Rupp’s pumps, when you imagine them don’t think on the scale of a fist-sized fuel pump. The three Gorman-Rupp municipal pumps (17 more are on order) installed in New Orleans—after Hurricane Katrina, it must be added—have intakes that are 12 feet high and 40 feet wide, are powered by 10,000-horsepower motors, and can pump a million gallons a minute.

And any mention of Gorman-Rupp wouldn’t be complete without saying that the company was a principal sponsor (along with AOPA and the AOPA Air Safety Institute) of Aviation Weather and its follow-on, AM Weather, the 1975-1995 Public Broadcasting System show specifically aimed at general aviation pilots. —TAH