Technological advances have taken us airborne and then some. Ingenuity grabbed the Wrights’ design and sprinted with it, and the results are tangible: jet engines speed us to international destinations; satellites help us navigate almost effortlessly; commercial space travel is within our grasp.

To get here, aviation’s innovators had to travel some rough roads. There were missteps and detours; instances in which technology failed to deliver on its promise—or initially delivered on that promise, only to fall by the wayside.

Beechcraft Baron flap/landing gear switch confusion (affecting all models prior to 1983). How does the venerable Beechcraft Baron end up on a list of technological shortcomings? To illustrate that when it comes to aviation, little things mean a lot. To wit: The National Transportation Safety Board conducted a special investigation in 1980 to determine why so many of the aircraft were involved in landing accidents. It found that nonstandard placement of the landing gear switch—to the right of the throttle quadrant, where most other manufacturers place the flap switch—was a large part of the problem. Pilots were raising the gear on landing, when they meant to retract the flaps. The gear switch was repositioned to conform with the industry standard on 1984 and later model Barons and Bonanza 36 models.

Concorde (1976-2003). Before you take out your baseball bats, let me qualify my inclusion of the Concorde on this list: The supersonic passenger jet was an engineering marvel. No other aircraft has carried passengers from New York to Paris in three and a half hours. Editor in Chief Tom Haines flew in the Concorde, and by his own description it was a thrilling experience.

But there are no more Concordes zipping across the sky. British Airways and Air France grounded their fleets in 2003, blaming rising maintenance costs coupled with low passenger numbers in the wake of a July 2000 crash—as well as a slump in air travel after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. No carrier has since brought supersonic flight back to the table. Have we given up on supersonic flight altogether?

In the ensuing years several companies have talked about concepts, but they’ll need to deal with issues such as lessening sonic booms and fuel emissions. Virgin Galactic’s Richard Branson has said he intends to tackle supersonic travel—after the company succeeds at commercial space travel (see “To Infinity and Beyond,” page 58).

Beechcraft Starship (1983-1995). I don’t mean to pick on Beechcraft (actually Raytheon at this point in the timeline). But no discussion of technology that didn’t pay off would be complete without a mention of the Starship, a twin-engine turboprop intended to be a successor to the King Air. Its radical design, which melded a pusher configuration, a canard, and carbon fiber composite materials, soon met the metaphorical brick wall of FAA certification. That process added more than 2,000 pounds to the end result.

More problems ensued when Raytheon/Beechcraft’s suppliers failed to deliver their subcomponents on time and caused delays in production. A free maintenance program for owners didn’t help move the inventory.

The $300 million Starship program culminated in the production of 53 aircraft. In fact, the design became such a liability for the company that it bought back most of the airframes and parked them. Four are said to be flying today.

The Starship has an avid fan base among the aviation community. Editor at Large Tom Horne flew a Starship, and he recalled that the airplane’s design had a positive effect on how it handled turbulence. “You knew you were in turbulence, but with less pitch excursions,” he said. You can see a Starship at the Beechcraft Heritage Museum at Tullahoma Municipal Airport in Tullahoma, Tennessee (see “Pilot Briefing: Fly-Ins,” page 48).

Flying cars (1917-2015). We’re so close to crossing the threshold from Popular Mechanics wish fulfillment to reality. The Terrafugia Transition conducted two-person flight tests in October 2014. The company is seeking performance-based certification standards because its required safety equipment pushes it over the weight limit for Light Sport aircraft.

All well and good—but shouldn’t we have had a flying car by now? Engineers have tried to incorporate automobiles (and motorcycles, and trikes) in their designs almost from the beginning. Glenn Curtiss gets credit for the first one in 1917, when he attempted to marry a triplane to a flivver.

“So far, blending cars and airplanes hasn’t gone well,” said Senior Editor Alton Marsh, who has written extensively on them. “[Highway] Crashworthiness standards make aircraft too heavy to fly in the Light Sport category, or just too heavy to perform well. Efforts have led to impractical cars that are slow in the air.”

Email [email protected]

Early designs. Aviation’s earliest days consist of a virtual minefield of designs that couldn’t get off the ground. Tractor monoplanes; biplanes with eight propellers; bicycle airplanes—if you could dream it, aviation’s dreamers likely thought of it first. The prototypes might have looked airworthy to their designers, but they weren’t.

Some failed designs were able to provide the basic ingredients for future success. And today’s innovators have continued to look to the past for inspiration: Gizmodo reported in 2013 that Alexander Graham Bell’s unsuccessful design for a flying machine was resurrected by a team of engineers and architects who repurposed it as a model for floating, solar-powered structures.

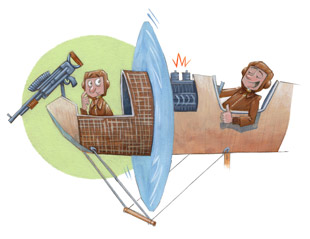

Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.9 (1915). The World War I-era fighter was likely more dangerous to its occupants than to any airplane it was designed to meet in combat. The B.E.9’s propeller and engine were located between the front gunner, who sat in a plywood nacelle, and the pilot. The design was intended to give the front gunner an unobstructed view of his targets. If the airplane crashed, the gunner could be crushed by the engine—or chewed up by the prop. Only one was built.

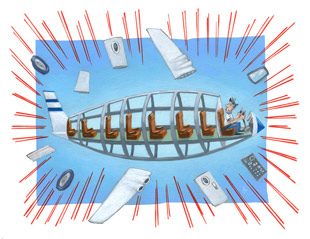

De Havilland Comet (1951). The United Kingdom beat the United States into the jet age when it brought the world’s first jet airliner into production. The pressurized de Havilland Comet showed great promise in its first year of commercial service, offering a relatively quiet, comfortable ride to a new generation of travelers.

A series of accidents in 1954 in which the airplanes broke up in flight revealed the cause to be metal fatigue resulting from pressurization. By 1958, de Havilland had redesigned the Comet and brought it back into production. But that same year Boeing put the 707 into service, which effectively put the Comet out of the race. The final two Comet 4 fuselages were used to build prototypes of the Hawker Siddeley Nimrod maritime patrol aircraft.

The microwave landing system (1970s-present). It’s not hard to understand why the FAA was keen on the microwave landing system (MLS). Instrument landing systems use 40 channels and frequency congest is a concern in busy metro areas, whereas MLS can accommodate 200 channels. ILS signal interference can be caused by reflections from nearby buildings, and terrain can impede the proper positioning of ILS transmitters—but MLS signals were produced by smaller antennae that formed narrow guidance beams, which could be more easily controlled and create a range of flexible approach paths. A 1974 FAA training film predicted, “By the end of this century, MLS will be serving international aviation as the worldwide standard for all-weather approach and landing.”

What happened? Three more initials: GPS. By 1994, the FAA had suspended the MLS program to put its resources into the Wide Area Augmentation System. MLS still exists in Europe, particularly in the United Kingdom.

The B.E.9’s propeller and engine were located between the front gunner, who sat in a plywood nacelle, and the pilot. The design was intended to give the front gunner an unobstructed view of his targets. If the airplane crashed, the gunner could be crushed by the engine—or chewed up by the prop. Only one was built.

A series of accidents in 1954 in which the airplanes broke up in flight revealed the cause to be metal fatigue resulting from pressurization. By 1958, de Havilland had redesigned the Comet and brought it back into production. But that same year Boeing put the 707 into service, which effectively put the Comet out of the race.

Engineers have tried to incorporate automobiles (and motorcycles and trikes) in their designs almost from the beginning. Glenn Curtiss gets credit for the first one in 1917, when he attempted to marry a triplane to a flivver.

Illustrations by John Sauer