Mission Colombia

GA is saving lives in remote regions of the world

As we approach our destination on the southwest coast of Colombia, Lenz suddenly unbuckles and moves forward to the cockpit. Beattie appears to be struggling to see through the coastal overcast, and Bentata asks Lenz what seem to be questions of immediacy. Yes, Lenz is saying, in his heavily accented English, yes, there. Does Bentata not know this approach? Has he not dropped this gorgeous airplane in this remote spot before? No, it seems he has not, and obviously neither has Beattie; she is accompanying us on this trip because she is a native of Colombia and speaks the language. We are flying VFR in what most would call instrument conditions; Bentata tells Beattie he terms it “quasi VFR.”

And then we are dropping down into the jungle, mangrove swamps and numerous rivers flowing below us to the Pacific Ocean. Lenz sits back and refastens his seat belt. The stall warning sounds and we touch down on a narrow strip, landing short and tight on an airport only yesterday cleared for this mission with machete and scythe. About 10 camouflaged, heavily armed soldiers greet us. Welcome to El Charco, Colombia, South America. It’s 100 degrees Fahrenheit and the humidity is stifling.

“Colombia is a big country; we have three big mountain ranges, deserts, jungles,” Lenz says. “We serve faraway communities in isolated places, transforming lives in Colombia.”

No gray area

Their service is the work of the Patrulla Aérea Civil Colombiana (PAC), the Civil Air Patrol of Colombia, based outside of Bogotá. Not like the U.S. Civil Air Patrol, but a group of pilots who, for the past 50 years, have used their $100 hamburger money to fly doctors and aid into the remote villages of Colombia. Bentata is an exiled Venezuelan who is heartbroken that he cannot help in his native country, so he volunteers his time and his aircraft in Colombia. Lenz is the president of PAC; his father was one of the original members.

“I love it. It’s my passion. It’s the best combination—flying and love for my country. I love my country. I love its people,” says Lenz.

The PAC is a nongovernmental organization (NGO) that was established in the late 1970s to provide care in remote areas of Colombia that its organizers—local private pilots—could fly to. As an NGO, it organizes and staffs missions into areas where medical care is limited. Doctors, nurses, and aid workers are transported into these remote areas by an assortment of aircraft, from Kodiak to Cessna 172s, and everything in between. The pilots are all volunteers, as are the medical staff. A small staff manages the PAC at the Guaymaral Airport, a GA airport outside of Bogotá.

The challenges in this remote, poor village include the obvious—no air conditioning, no cars, very little clean running water. Most of the Pacific coast of Colombia is inhabited by Afro-Colombians, descendants of freed and escaped slaves who fled here in the late eighteenth century. Only the United States and Brazil have larger black populations outside Africa; about 10 percent of Colombia is of African descent. Separate and across the river from the main center of El Charco is an indigenous tribe of native Colombians.

The concrete-block building where we are headed is a former school and clinic that is vacant most of the time (there is a local doctor who practices for a fee here). The airstrip we landed on cannot accommodate the other aircraft flying from Bogotá; the doctors and nurses land farther down the Tapaje River at Guapi and take a longer boat trip to El Charco. As we walk through the streets, a man on a small motorbike is announcing the arrival of the doctors on a bullhorn. The clinic sets up here about once a year. Villagers have been notified and appointments taken, but the announcement is to both remind and nudge people to take advantage of this two-day makeshift hospital, which does not charge patients for services.

“The volunteers are the heroes of this story,” Lenz says of the cadre of doctors, nurses, and aid workers who take time off from their jobs to spend weekends working.

Patients are lined up with IVs in their arms, waiting for the next open surgical bed. Operations for hernias, growths, and even a hysterectomy will take place side by side in this field hospital.

Then the pace of the day is interrupted by an emergency. A young girl is brought in, near death from respiratory complications of an advanced case of sickle cell anemia, and she must be transported to the closest modern hospital, a two-hour flight. Strapped on a gurney and with a full-size oxygen tank keeping her breathing, she must first be put on a boat to go back upriver to where we landed. Veteran PAC pilot Hans Timcke in his Piper Seneca II makes the flight in and out. The gurney moves through town and then down the boat ramp amid a crowd of medical support staff on foot. “After carrying the gurney through those dirt streets and down 10 slippery steps to the boat, they just had that motor wide open, up the river,” AOPA Photographer Chris Rose remembered later. “The time from when we left the clinic to the time the aircraft took off was much faster than I could have imagined; probably faster than a medical transport through a big city.”

The attending doctor tells us what would have happened if an aircraft wasn’t available. “We would have watched her die,” she said. “It’s volunteer general aviation aircraft or death in a situation like this. There is no gray area.”

Lost in translation

Luz Beattie left Colombia when she was 8 years old and has only been back once, to pick up her adopted son. She remembers foods, and smells, and the language, but even then, some are as foreign to her as they are to us.

A 11,600-hour pilot who has flown 20-plus aircraft and is an airline transport pilot, she seizes the opportunity to fly right seat in the Kodiak on this 270-nautical-mile flight from Bogotá.

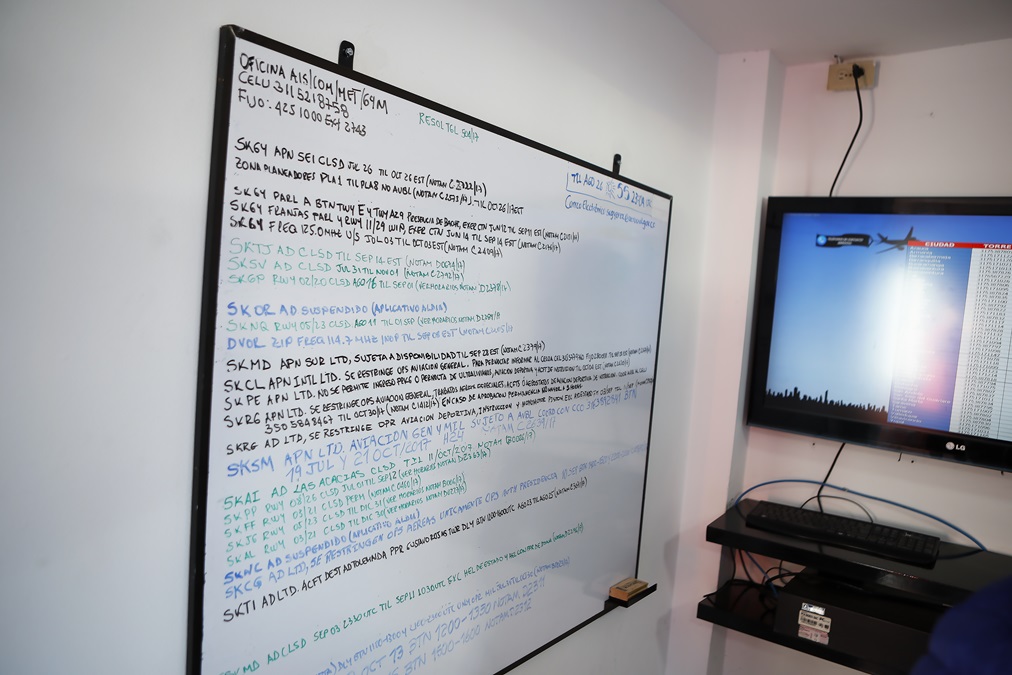

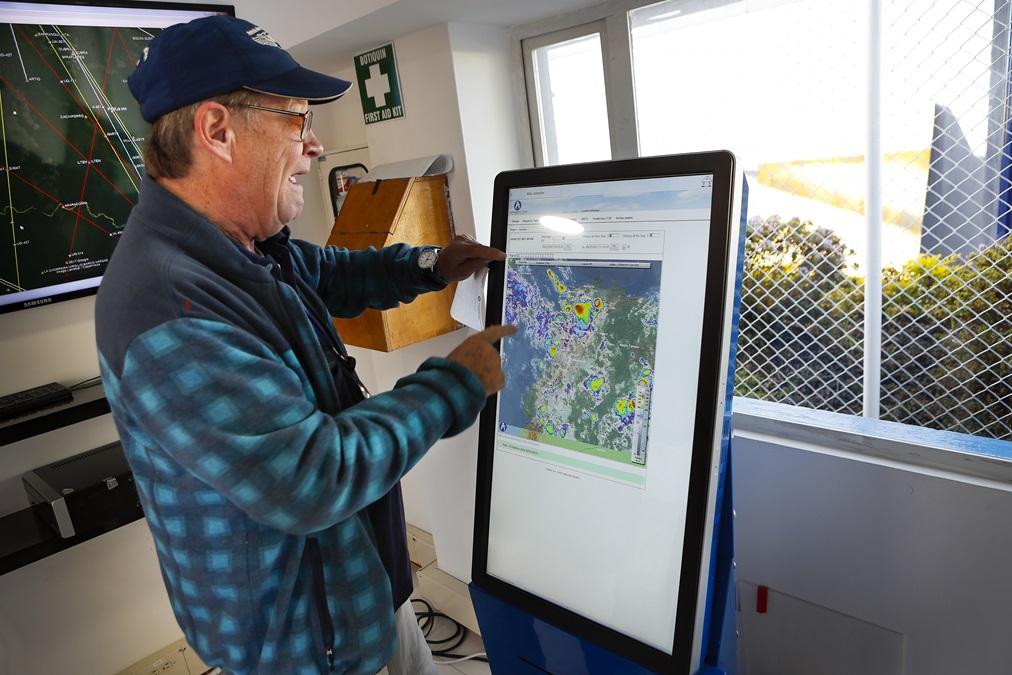

“Even though they told me that filing a flight plan is getting easier, it still was a long process,” she says. “Flying VFR, you still have to fly a flight plan and are always in radio contact. Karel called it ‘quasi-VFR.’ You’re starting out at an altitude of 8,000 feet msl and need to cross the Andes in an unpressurized airplane. It’s almost impossible to count on a totally clear day. Plus, the airport they use—Guaymaral—is just north of Bogotá’s international airport so you have to remain below the Class B.”

She’s thrilled to make the flight, but once on the ground and in El Charco, her demeanor changes. Her eyes are wide at the muddy roads and crumbling structures around us. The smells of rotting garbage and fish drying in the sun and heat are overwhelming. There are dogs everywhere, and Beattie and an aid worker adopt a dog for the day, feeding him scraps and petting him.

In the middle of the night a storm pummels the town, making a muddy stream of the dirt streets. Morning is a hot, dry, welcome relief.

When Rose leaves with the hospital boat, Beattie and I sit along the boat ramp watching the kids find games to play with pieces of Styrofoam and sticks that are floating down the river. A young girl sits on the stairs and washes her hair. A group of boys bring their soccer uniforms and wash them in the river, too.

“I saw a strong sense of community in El Charco,” Beattie says after we return. “I saw how much they rallied for that little girl to try to get her out for treatment they couldn’t provide.”

The night before, we shared dinner at a home-based restaurant that was situated along the river. In the waning light of the sun setting out toward the Pacific and with the river flowing before us, we are struck by the natural beauty.

The PAC

The Kodiak isn’t the only aircraft that is taking on the mission of the PAC in Colombia. From Cherokees to Caravans, these airplanes and their pilots fly doctors, nurses, and medical supplies all over the country. What could have been an easy out to simply hang around the airport and fly in this lush, mountainous country is instead a lifeline of aid to places nearly impossible to get to any other way.

“The PAC is an organization dedicated to transforming lives,” said Lenz. And although he means the delivering of aid, the transformation of the pilots’ lives is remarkable, too. The challenges of flying in this diverse country with its mountains, deserts, and ever-changing weather test skills, demand good aeronautical decision making, and intensify the camaraderie of the flying community. Members of this group come from all walks of life and congregate throughout the year to plan missions. They range in age from nearly 80 to 20-somethings, sons and daughters of the original group who founded the PAC in the 1970s.

Lenz says the challenges have changed since his father flew for the PAC, especially since the violent drug years of the 1980s. But the bureaucracy remains. When called to evacuate the young girl, Lenz spent a tense time on his cellphone getting through red tape. “We had to call the vice minister just to save her,” he said. “We have a 51-year history of making things right, of saving people.”

Lenz estimates that the missions PAC undertakes cost about $30,000 per weekend. That’s the costs of the medicines, supplies, and the logistics. PAC coordinates 12 missions each year, and the doctors perform 1,200 surgical procedures and 15,000 medical attentions, he said. The doctors and nurses are all volunteers; the fuel for the aircraft is donated by Terpel, a major Colombian gas company. In fact, the president of Terpel is the fiancée of one of the pilots on this mission to El Charco.

“This gives you life,” said Lenz. “Seeing what you can do and providing just a little help, you can change a life. It is good for your soul.”

We learn, once we are back in the States, that the young girl survived.

Email [email protected]