Clouded judgment

Are instrument conditions brewing up ahead? Avoid the common mental traps

He said it was the most valuable lesson he learned—not only during the course, but in all of his riding experience since. “What if I didn’t crash? If I had to make an emergency stop on the highway, I would have tried to brake the same way and probably paid for it with my life. Now I’m more cautious when I have to stop, especially quickly, because I’m well aware of what can happen and that it can happen to me,” my friend said.

In the same way, the controlled environment of flight training may lead pilots to be overconfident in assessing the risk of an encounter with instrument meteorological conditions (IMC). Can anyone consistently abide by their own limitations unless they’ve tested them at some point?

VFR flight into IMC continues to be one of general aviation’s deadliest accident causes. These types of accidents are highly preventable—so why do competent, rational pilots fly under visual flight rules into disorienting low-visibility conditions without training or preparation? One reason may be that pilots don’t understand how dangerous it actually is—or they misunderstand how these encounters happen in the real world.

What makes IMC so dangerous? Spatial disorientation. When pilots lose outside visual references in low visibility, the inner ear generates false sensations that can lead the pilot to believe the airplane’s attitude has changed when it hasn’t. Instrument-rated pilots are trained to rely on the flight instruments to determine the aircraft’s attitude and motion, but untrained pilots react to what their body is telling them.

Many pilots never fly into actual IMC during training. It’s simulated using a view-limiting device. Simulated instrument conditions are instantaneous: One second you’re flying VFR under a clear blue sky, the next, you’re flying with an odd-looking hood over your head and can’t see outside the airplane. In the real world, flying into IMC isn’t that simple. The weather can deteriorate in a matter of minutes or hours, and either scenario can catch a pilot off-guard.

The solution to inadvertent flight into IMC that’s offered in training sounds easy enough: Make a 180-degree turn if you enter a cloud. This may contribute to pilots pushing forward into worsening weather, because they can always get out of it if necessary. But what happens when the weather deteriorates so quickly that behind you isn’t any better? The best defense is avoiding IMC in the first place.

What if you’ll only be flying in IMC for a few minutes, just to get through that small patch of fog hovering over the airport? In 1954, the AOPA Foundation (now the AOPA Air Safety Institute) commissioned a study by the University of Illinois about VFR pilots flying into IMC with no instrument training. Twenty pilots flew into simulated IMC and all lost control, in an average of 178 seconds (see “The Bright Side of ‘178 Seconds’”).

Flight instructors could help students by introducing them to marginal VFR conditions during flight and letting them experience how disorienting marginal VFR can be first-hand. They also can schedule an IFR flight when normally the lesson would be canceled. Students can benefit from experiencing the sensations of flying into actual IMC, and they can practice a proper instrument scan without the hood.

Instrument-rated pilots may fly in clouds safely while on an IFR flight plan, following guidance from navigational aids and communicating with air traffic control. But flying into clouds without an instrument rating is a bona fide emergency. Avoiding instrument conditions starts with a check of the weather.

“Always check the weather before each flight,” said Harold Green, flight instructor at Morey Airplane Company in Middleton, Wisconsin. “You’re responsible to obtain any and all information pertaining to your flight. You can’t avoid what you don’t know is out there.”

The solution to inadvertent flight into IMC that’s offered in training sounds easy enough: Make a 180-degree turn if you enter a cloud.Pilots can obtain a weather briefing by phone at 800-WX-BRIEF, online from the Leidos portal (www.1800wxbrief.com), or via a connected app. In addition to the standard weather briefing, the Aviation Digital Data Service (www.aviationweather.gov/adds) is an excellent supplemental source for weather information. It provides up-to-date weather forecasts, METARs, and any airmets that have recently been issued. Airmets are issued when IFR conditions and extensive mountain obscuration exist in a large geographical area. They’re also issued when a location is affected by significant turbulence and icing. If one has been issued for an area you’ll fly through, better to wait for the weather to clear or take an alternate route.

Generated once every hour, aviation routine weather reports (METARs) are an excellent source for current weather information at a specific airport. Pay close attention to the temperature-dew point spread. A zero- to two-degree difference is a sign that low ceilings, precipitation, and poor visibility should be expected. Using previously recorded METARs is a great way to identify trends and converging temperature-dew point spreads. This can help you “see” what the weather is actually doing and where it may be headed in the future. Some airports have terminal aerodrome forecasts (TAFs) that forecast weather at that location for a 24-hour period.

The Aviation Digital Data Service also provides several charts, such as the weather depiction chart. This chart clearly shows which areas are currently IFR, marginal VFR, and VFR. Shaded areas are currently IFR, and areas within unshaded contoured lines are marginal VFR. Marginal VFR (MVFR) areas have ceilings of 1,000 to 3,000 feet and/or visibility of three to five miles. Although MVFR conditions meet the FAA’s required minimums for VFR flight, many pilots should and do choose to avoid flying through them. Ask yourself what visibility, ceiling height, and wind conditions you feel safe flying in, and use them as your own personal weather minimums.

The changeability of weather is one reason why it’s critical to have a backup plan. Without one, pilots can feel they don’t have any alternative other than flying through worsening weather.Even after a preflight weather check, it’s important to continually evaluate conditions while flying (see “Almost magical,” at left). In flight, slowly deteriorating weather conditions can be more dangerous than when patterns change rapidly. Our eyes can become used to small changes in our environment that we don’t notice until severe weather appears as if it came out of nowhere. This dynamic can catch an unsuspecting pilot off guard and unready to deal with the change in weather. Green said, “When humidity is high and the sun is low, one can get into IMC just by turning into the sun.” A cloud layer can form without notice if you don’t consistently maintain a proper scan outside the cockpit. That includes above and below you. Pilots should assume they’re in instrument conditions any time they’re unable to maintain attitude by reference to the natural horizon.

The changeability of weather is one reason why it’s critical to have a backup plan. Without one, pilots can feel they don’t have any alternative other than flying through worsening weather. In preflight planning, include ways you’ll monitor the weather during the flight, alternate airports at which you can land, and alternate routes you’ll fly if the weather deteriorates significantly.

It can be increasingly difficult to stick to your plan as you get closer to your destination. This is often because you’re flying a familiar route or you’ve flown in similar conditions without incident. You may also feel pressured to land because of passengers on board or fear of losing your job if you don’t get to your destination on time. This causes the line between the right and wrong choice to become blurred. A pilot’s ego can take over and decide to push on, often with fatal consequences. “Never be in a position where you must complete the flight.” Green said. “Leave the business issues—and your ego—in your car at the airport parking lot.”

There were 21 noncommercial fixed wing accidents that involved direct flight from VFR into IMC in 2015, according to the AOPA Air Safety Institute’s twenty-seventh Joseph T. Nall Report; 20 were fatal. There’s an old adage in flying: Use your superior judgment to avoid getting yourself in a position where you need your superior skill to survive.

Scott Hotaling is a freelance writer living in New York.

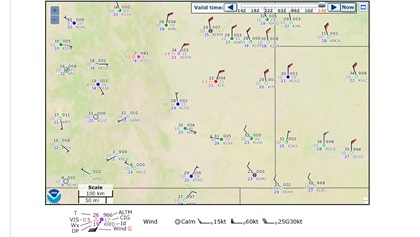

Resources such as this METAR map from the National Weather Service’s Aviation Weather Center can help pilots visualize current conditions in an area. It may be VFR with light winds at La Junta Municipal Airport (LHX) in Colorado, but conditions are worse to the north and northwest, with Colorado Springs (COS) reporting marginal VFR and Limon Municipal Airport IFR. Gusty winds and snow also would meet any flying northbound from La Junta.

Resources such as this METAR map from the National Weather Service’s Aviation Weather Center can help pilots visualize current conditions in an area. It may be VFR with light winds at La Junta Municipal Airport (LHX) in Colorado, but conditions are worse to the north and northwest, with Colorado Springs (COS) reporting marginal VFR and Limon Municipal Airport IFR. Gusty winds and snow also would meet any flying northbound from La Junta. Today’s tools for avoiding inadvertent IMC encounters would seem magical to previous generations of pilots, who had little more to go on than intuition. Today’s most widely used tablet apps (ForeFlight and Garmin Pilot) are so good that I struggle to imagine ways to improve them—and I wonder how we ever got by without them.

Today’s tools for avoiding inadvertent IMC encounters would seem magical to previous generations of pilots, who had little more to go on than intuition. Today’s most widely used tablet apps (ForeFlight and Garmin Pilot) are so good that I struggle to imagine ways to improve them—and I wonder how we ever got by without them.