The bane of new instrument pilots, especially during initial training, is an attention-deficit-disorder-like feeling that their eyes are moving—or should be moving—all the time. To be honest, the eyes of the best instrument pilots probably are moving all the time. The real trick is to know what instruments to scan and when, a task made more difficult when a pilot’s head is looking down at the panel when he should be looking out the window, and vice versa. The exercise is repeated many times until either the runway lights appear through the mist, or the altimeter hits the decision height—signaling a missed approach.

The bane of new instrument pilots, especially during initial training, is an attention-deficit-disorder-like feeling that their eyes are moving—or should be moving—all the time. To be honest, the eyes of the best instrument pilots probably are moving all the time. The real trick is to know what instruments to scan and when, a task made more difficult when a pilot’s head is looking down at the panel when he should be looking out the window, and vice versa. The exercise is repeated many times until either the runway lights appear through the mist, or the altimeter hits the decision height—signaling a missed approach.

The military realized long ago that landing and taking off are visual events and require considerable pilot attention. Pilots of a single-seat fighter were especially vulnerable to head gyrations, which turned out to be even more dangerous close vulnerable to head gyrations, which turned out to be even more dangerous close to the ground at 140 knots on final. Tie those safety concerns together with some NASA research, mix in a handful of Department of Defense money, and voila! you have the head-up display or generically, the HUD. HUDs—created by companies such as Honeywell, Rockwell Collins, and Thales—have fostered technologies to make flying safer, especially for single-pilot aircraft, while improving situational awareness. HUDs concentrate all the important flight and navigation information for pilots to view in one location, which reduces neck aches to a minimum. Alaska Airlines began using early HUDs in 1987, units built by Flight Dynamics—which trademarked the name Head-Up Guidance System (HGS) for its version. The Alaska installations also proved pilots could fly aircraft safely to lower IFR approach minimums. Southwest Airlines ordered hundreds of Rockwell Collins HGS units for its new Boeing 737s and as a retrofit for some models flying the line today.

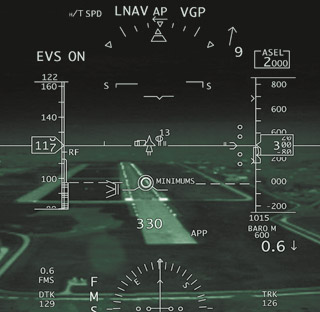

The HUD/HGS concept is really simple. Place a piece of clear glass (called a combiner) about 12 to 18 inches in front of the flying pilot as he stares out the cockpit window, and his eyes will quickly forget that the glass is even there. Now, while pilots are staring out the front window—looking for really important items such as the runway or other airplanes—the HGS also projects critical flight and navigation numbers, and other information gathered from the traditional instruments. This means pilots can now see heading, airspeed, altitude, and navigation information without alternating between head up and head down. Mean times between failures for the equipment are almost nonissues when the computers monitor themselves hundreds of times each second.

Now also imagine that in addition to being able to see the most basic of IFR information, a Head-Up Guidance System such as Rockwell Collins’ smallest, the HGS-3500, also provides the pilot with flight-path cues that show precisely where the airplane is tracking, not heading, based on current speed and power setting. Wonder where you’ll touch down on the runway with your current power setting? The flight path cue will show you precisely—not close, but smack dab on the spot. Thanks to a link to the aircraft’s inertial reference system, visual cues also include acceleration/deceleration markers that visually demonstrate airspeed trend information if power and pitch conditions remain the same, a handy item when trying to peg an airspeed on final approach. The HGS can be a tremendous help in VFR conditions, too. Want to know for sure whether your aircraft will clear that line of hills 10 miles ahead at your current altitude? The flight path cue tells all, even confirming which engine just died during a power failure in a twin.

Just when your eyes are already growing wide at the sheer mention of these fabulous feats of HGS flying comes one more: An HGS can reduce IFR landing minimums, which is one of the truly important reasons both airlines and business jet operators are installing the units. Imagine almost no more missed approaches. Category II minimums—100-foot ceilings and 1,200-foot runway visual range (RVR; think six runway lights) become a piece of cake.

Low-visibility takeoffs are easier and safer with the precise runway guidance an HGS delivers. On those risky nighttime nonprecision approaches, an HGS can precisely pinpoint the aircraft’s flight path and touchdown spot in total darkness at a small airport in the mountains, with few lights for reference. TCAS and wind shear advisories also are displayed on the HGS combiner screen. Imagine breaking out of a 200-foot ceiling at night in the rain—the visual effects can be both blinding and confusing. The HGS assists the pilot by announcing the precise place to flare for a near-perfect arrival every time. The HGS also provides accurate rollout guidance; even unusual-attitude recovery cues and synthetic vision are available head up.

Head-up display technology is still immersed in some growing pains, despite its operational debut a decade or two back. The projector that displays all the nifty flight and navigational technology on the combiner is still rather bulky and normally found attached to the cockpit ceiling, which means aircraft with limited headroom probably aren’t HUD candidates—yet.

Rockwell Collins and other avionics manufacturers offer units for various Boeing, Bombardier, Embraer, Dassault, Gulfstream, and Cessna models, as well as a number of military transports. The smallest aircraft that will accept the HGS-3500 is a Beech King Air or a Cessna Citation Mustang, so pilots of singles such as TBMs, Cirrus, and Meridians are going to need to wait. I remember when cellphones weighed five pounds and required a shoulder strap—can a Cirrus with a HUD be far behind?

For pilots hankering for a closer look at the Rockwell Collins HGS, only an iPad is required. Aviators so equipped can download the company’s “HGS Flight” app from the App Store for free.