You can find one over the Arctic, or over Manhattan. Martha Stewart has one, and you might too. Some are very small and others can be rather large. From search-and-rescue missions to crop surveying; from capturing movie action sequences to starring in them—unmanned aircraft systems have progressed from a niche hobby to a booming industry.

Proponents of unmanned aircraft systems (UAS)—sometimes called drones or unmanned aerial vehicles—point to the technology’s potential to take humans out of harm’s way and cut costs, sometimes by orders of magnitude. Yet only recently has a regulatory framework been proposed to begin the process of safely integrating these diverse systems with other users of the national airspace—users that have humans on board. In the regulatory vacuum, a few companies have obtained ad hoc approval to fly in remote or protected places. Others have staked their businesses on the creation of regulations that have been slow to come. Still others have simply flown anyway.

A much lower cost. The Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) estimates that unmanned aircraft can cost as little as $25 an hour to operate, while a helicopter may cost hundreds. Small UASs also have the benefit of producing less downwash and less noise. Schuster added that his aircraft’s light weight makes them safer in the filming environment.

Proving that Vortex Aerial’s aircraft would operate with an equivalent level of safety to existing rules—a current requirement for the FAA’s case-by-case approvals of commercial UAS operations—took about four years and involved a redesign of the company’s aircraft, said Schuster. The terms of the exemption include a number of operating limitations, including controlling access to the shooting site perimeter and having an operator with at least a private pilot certificate.

Obtaining approval to operate unmanned aircraft in the United States for commercial purposes hasn’t been easy. In fact, the FAA didn’t authorize the first commercial UAS operations over land until July 2014, and that was for a remote area of the Arctic. So why does it seem like an unmanned aircraft makes the news weekly for filming cityscapes or photographing weddings and real estate? According to the FAA, which draws a hard line between “model aircraft” flown by hobbyists and “unmanned aircraft systems” flown for profit, these commercial operations are prohibited without the agency’s authorization.

For pilot, model aircraft hobbyist, and Atlanta Hobby President Cliff Whitney, that just doesn’t make sense. Hobbyists have long flown safely under a few simple guidelines from the FAA and with support from the Academy of Model Aeronautics (which, he pointed out, predates the FAA). As model aircraft have gotten easier and safer to fly, he said, more people have begun to participate in the hobby. His small company, which sells aircraft such as the popular DJI Phantom quadcopter, added 22 people in 2014 and he was looking for five to 10 more, he said.

Photographers, in particular, have recognized the utility of the systems and are snapping up low-cost, lightweight multirotor helicopters, many customized with gimbals for smooth video and other photography-specific accessories. Whitney said his most popular configuration—a multicopter with a camera, extra batteries, and case—sells for slightly less than $3,000, and he generally has about 200 backordered.

So what makes a hobbyist who photographs his own house for amusement safer than a realtor who photographs a home to sell it? Is someone flying for business more likely to take risks? Whitney thinks the FAA is being too tough on what he calls “lite commercial.” If someone is operating expensive equipment, he reasons that the commercial operator will be safer and more efficient because his livelihood depends on it.

Whether they’re flying for fun or money, more operators are sending unmanned aircraft into the airspace than ever before—and many don’t know, or don’t care, about standards for operating safely. Jim Williams, manager of the FAA UAS Integration Office, told an audience at the UAS Action Summit in Grand Forks, North Dakota, in June 2014 that there had been a huge increase in pilot reports of incidents involving unmanned or model aircraft.

The agency has tried to rein in both. While it can’t regulate model aircraft, the FAA asserted its prerogative in June to take enforcement action against operators if they endanger the safety of the National Airspace System. The same document also set out restrictions on model aircraft operations (including prohibited commercial activities) that the hobby community thought overstepped longstanding guidelines.

Whitney says the answer isn’t more restrictions. He said every unit that comes out of his shop comes with the advisory circular governing model aircraft operations and an invitation to more advanced training, with information on how to connect with the Academy of Model Aeronautics. “Education is the key to all this stuff,” he said.

Dirty, dangerous, difficult, dull

Forty years ago, his father could scout 40 acres in a day. Then, with a four-wheeler, it was 400 acres. Now, said Mitchell Fiene, co-founder of DMZ Aerial, a quadcopter can scout thousands of acres of fields in one day. Fiene parlayed a hobby of working with unmanned aircraft into a start-up business, modifying the aircraft for precision agriculture. His family’s company customizes consumer systems with gimbal-stabilized camera or multispectral imaging equipment and sells them to customers who want to identify problem areas in croplands. He’s been waiting for the small UAS regulations so he can offer aerial scouting as a service.

According to Michael Toscano, former president and CEO of AUVSI, precision agriculture is a good proving ground for unmanned aircraft systems because the likelihood of a person being in that space is low. He stresses that unmanned systems help people do their jobs more effectively, particularly when it comes to the “Four Ds:” Missions that are dirty, dangerous, difficult, or dull.

“Men and women know how to do their job,” he said. “But they do want to come home.” According to AUVSI, crop dusters have the third highest fatality rate among professions in the United States. Unmanned aircraft already are being used in other countries and through research authorizations—and, in some cases, in defiance of the FAA—to apply pesticides and survey fields; the association says 80 percent of the projected market for UAS is in agriculture. Toscano also sees potential in public safety fields such as search-and-rescue operations and firefighting. When firefighters at a quarry fire near New Haven, Connecticut, were uncertain how close the fire had gotten to explosives on site, an unmanned aircraft gave them an aerial view of the scene.

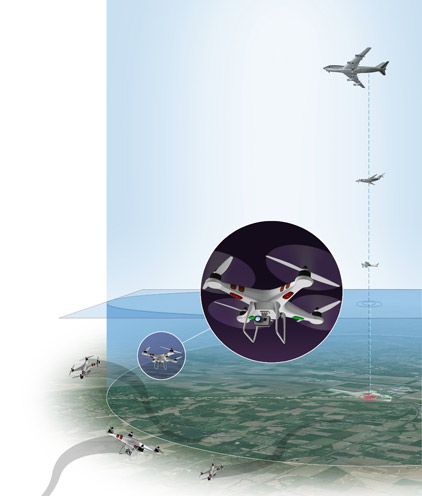

While they may take humans out of harm’s way in hazardous occupations, the challenge in integrating these systems into the national airspace will be to ensure their presence doesn’t put other humans in harm’s way. Regulations recently proposed by the FAA impose altitude restrictions on small UAS, but as AOPA Vice President of Regulatory Affairs Melissa Rudinger reminded a group of UAS industry professionals at the UAS Action Summit, flying at low altitudes does not eliminate the collision hazard with many types of general aviation: lighter-than-air flights, helicopters, and low-altitude piston missions like aerial application.

Delivery by drone?

From browsing products online to a package on your doorstep in 30 minutes or less: That’s the UAS-based vision of Amazon Prime Air.

“One day, seeing Prime Air vehicles will be as normal as seeing mail trucks on the road,” Amazon says in frequently asked questions about the UAS delivery service. The company has been testing the use of small multicopters to carry up to five-pound payloads, which Amazon says covers 86 percent of products sold on its website, and has requested exemptions to take its testing outdoors in the United States. When the FAA grants permission, Amazon says, the company will be ready.

Navigating suburban neighborhoods surely presents more technological and safety challenges than shooting video on a closed set, but Amazon isn’t the only heavy hitter to throw its hat in the ring: The Google X team is developing an unmanned aircraft delivery system it calls Project Wing.

So will we soon grow accustomed to the whir of unmanned aircraft swooping in to drop movie merchandise on our neighbor’s doorstep? Not under proposed rules from the FAA, which would require small unmanned aircraft to remain within line of sight of the operator or a visual observer, and prohibit the aircraft from operating over people not directly involved in their operation. A survey of residents in northeastern North Dakota, where researchers are flying unmanned aircraft under a certificate of authorization, found that public support waned when it came to commercial deliveries, with respondents citing concern over airspace safety and the safety of those on the ground.

But Toscano thinks public support for unmanned aircraft systems will grow as the technology is fielded. As people learn more about the technology’s capabilities, he said, they will be able to decide how much risk to accept. First, Toscano said that it must be proven in areas with minimal human presence, and then it can progress: “Crawl, walk, run.”

Email [email protected]

Regs to set ground rules for unmanned ops

AOPA has two main goals in its advocacy on the integration of unmanned aircraft systems into the National Airspace System: preserving safety and protecting access for general aviation pilots.

With rapid advancements of UAS technologies, AOPA recognized early that clear rules were needed to ensure that the introduction of unmanned aircraft wouldn’t endanger people or require dedicated airspace that shuts out pilots. The association formally asked the FAA in 2004 to task an advisory committee with developing consensus standards for unmanned aircraft that weigh 55 pounds or less. The FAA established the committee; AOPA served on it, helping to provide recommendations; and the FAA accepted the consensus standards in 2007 and proposed rules for small UAS in February 2015.

AOPA maintains that in general, unmanned aircraft should be appropriately maintained and registered, be flown by a certificated pilot, and be flown in compliance with current operating rules and airspace requirements. The proposed rule for small, commercial unmanned aircraft would address many of AOPA’s concerns by requiring them to “see and avoid” other aircraft and setting certification requirements for UAS operators. It also would require small unmanned aircraft flown for other than recreational purposes to obtain an FAA registration and display an N number; operators would be required to conduct a preflight safety inspection before each flight. The FAA is seeking input on whether to create a subset of rules for aircraft weighing 4.4 pounds or less. The proposed regulations are open for comment through April 24.

The publishing of proposed rules is welcome progress for an industry that has been frustrated by the pace of rulemaking. An Inspector General audit found that the FAA was behind schedule in its attempt to meet Congress’s 2015 deadline for integrating these systems into U.S. airspace, and called into question when and if full integration of unmanned aircraft into the National Airspace System will occur. That’s caused uncertainty for existing airspace users, as well as for an industry poised to take off.

“I would say there’s very few industries that want to be regulated,” Michael Toscano, former president and CEO of AUVSI. “We’re one of them.” —SSD

Model aircraft dos and don’ts

In the summer of 2014, the FAA asserted its enforcement authority over model aircraft and issued these guidelines for hobbyists:

Dos

• Do fly a model aircraft/UAS at the local model aircraft club

• Do take lessons and learn to fly safely

• Do contact the airport or control tower when flying within 5 miles of the airport

• Do fly a model aircraft for personal enjoyment

Don’ts

• Don’t fly near manned aircraft

• Don’t fly beyond line of sight of the operator

• Don’t fly an aircraft weighing more than 55 pounds unless it’s certified by an aeromodeling community-based organization

• Don’t fly contrary to your aeromodeling community-based safety guidelines

• Don’t fly model aircraft for payment or commercial purposes

For more information, visit the website.

No fly zones

Don’t want UAS flying over you and your property? Pilot Ben Marcus created the website (www.noflyzone.org) to allow the public to post their property addresses, which get entered into a database. UAS manufacturers can voluntarily choose to include the associated coordinates in their drone’s programming. In doing so, the drones will not fly over those properties. The database already includes airports, hospitals, schools, and other sensitive locations.

FAA proposal sets rules for small UAS

The FAA’s proposed rule for small unmanned aircraft systems would set requirements for systems weighing 55 pounds or less used for commercial purposes. Among them, the FAA sets out requirements for see-and-avoid capability, operator certification, and aircraft registration.

• Operators must see and avoid other aircraft, giving right of way to manned aircraft.

• Operators must be at least 17 years old, obtain an FAA-issued unmanned aircraft operator certificate with a small UAS rating, and pass an FAA-administered knowledge test every two years.

• Aircraft must obtain an FAA registration and display an N number. A preflight safety inspection is required before each flight.

• Flights are limited to daylight, line-of-sight operations with a least 3 statute miles visibility at speeds of less than 100 mph and altitudes below 500 feet.

• The aircraft may not operate over people, except those involved in the flight.

• The systems must remain outside of Class A airspace. Operations in Class B, C, and D airspace, as well as within the lateral boundaries of the surface area of Class E airspace, can be allowed with prior permission from air traffic control.

• Aircraft must remain at least 500 feet below clouds and 2,000 feet from them horizontally.

Pilots may read and comment on the full proposal, “Operation and Certification of Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems,” in the Federal Register.

As technology advances, small, unmanned consumer aircraft get cheaper and easier to use, and can be paired with better, lighter cameras. High-end systems get more capable and more complex, making them desirable for specialized missions. Companies large and small see profit and promise in unmanned aircraft systems, and they’re not likely to go away anytime soon.

Lights, camera, action

When a car is rammed off a ledge and plunges to the ground in the Keanu Reeves action film John Wick, the audience sees the crushing metal from the vantage point of a lightweight multicopter.

“You could have done a shot like that with a manned aircraft, but the amount of risk that would have been involved would have been crazy,” said Chris Schuster of Vortex Aerial, one of six companies that received an exemption from the FAA in September to operate small unmanned aircraft to film for movies and television. Vortex uses aircraft that range in gross weight from 12 to 35 pounds. Unmanned aircraft can sometimes get shots that are more intimate and dynamic with a higher degree of safety, simplicity, and efficiency—and at a lower cost, he added.

How high can they fly?

While commercial unmanned aircraft systems operations are still only allowed on a case-by-case basis, hobbyists may operate model aircraft without FAA approval. That’s no license for reckless behavior, however. According to FAA guidance, model aircraft operators should fly no higher than 400 feet agl and contact the airport or control tower when flying within five miles of an airport. It’s the unmanned aircraft operator’s responsibility to fly safely and stay away from manned aircraft, which usually—but not always—fly at higher altitudes. —SSD

SPEC SHEET

DJI PHANTOM Price/ $479

Marketing/”Your Flying Camera”

Features/Ready-to-fly multirotor system with GoPro mount; training platform for new pilots

Website/www.dji.com/product/phantom

PARROT BEBOP Price/ $499.95

Marketing/“True Piloting Experience”

Features/Two “ultra-precise” joysticks with a fisheye camera

Website/www.parrot.com/fr/products/bebop-drone/

HUBSAN Price/ $173

Marketing/“Fly With Your Dreams”

Features/Quad Copter with camera

Website/www.hubsan.com/productinfo

PUMA AE Price/ NA

Marketing/”Human Power”

Features/Commercial applications such as first-responders; 40-minute endurance

Website/www.avinc.com/public-safety/solution/puma-ae-uas