How will you fly when no one is watching?

My most significant aviation learning started when my small airplane finally came to a stop with the right main gear and the tailwheel off the end of the Lagubang airstrip in the mountains of the southern Philippines. I can talk about the waterlogged surface; the tricky, shifting winds; the dogleg that had to be negotiated; the dropoff on the right side; the rise just off the left wing tip; the well-traveled footpath that defined the end of the strip or the bamboo village house just past the footpath. But the real talk is about how to apply those lessons learned in the jungle to every flight, every pilot, everywhere. I call them the Lagubang lessons.

A Helio Courier can get stopped easily on an 830-foot airstrip, and I had managed to do that two times in the preceding few hours. But a touch of tailwind combined with a few extra knots of airspeed on final resulted in an uphill hydroplane that made the little boys on the path—and the thatched roof house immediately beyond them—grow so rapidly in my windscreen that I was sure we would all end up in one fatal heap.

A last-second intentional ground loop created enough drag to stop us just short of that fully expected disaster. The tailwheel was a little wrenched from its socket, and the right horizontal stabilator now had a clumsy dihedral, but other than those two surmountable obstacles, all was well. Both the airplane and I would fly again—but how would I fly from that point forward?

In the accident debrief our safety officer said something so simple and so profound that I’ve never forgotten it. In fact, in more than 15,000 landings since then—many of them at that very airstrip—it’s come to mind every single time. He said, “Dan, every landing is a maximum effort maneuver.” Based on my accident narrative it was plain that, although I was not totally complacent, I had become slightly more casual on that final approach. No federal aviation regulations, no standard operating procedure, no airplane flight manual, no air traffic control, no training, and no technology can prevent that. It all comes down to professional self-discipline.

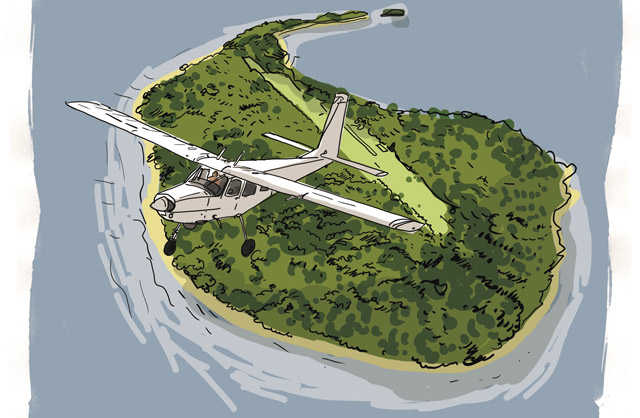

Flying on the island of Mindanao was a blast. As a pilot with the Summer Institute of Linguistics, I flew missionaries in and out of otherwise inaccessible locations. There weren’t any other airplanes down low where we flew, and no ATC. At 6,500 feet the air was drier and cooler, so we usually cruised in that vicinity. But if you wanted to fly near the treetops, no one was there to stop you, and the upper limits were defined by your lungs. Anywhere in between was fair game.

I had a chief pilot at the time who occasionally took liberties. We had some written standards, but he was mission-oriented and he always got the job done and came back unscathed. Sometimes standards yielded to the mission. I was new, and impressed. I understood the written rules, but now I thought I understood the unwritten rules as well. Leadership had spoken by example, and I had listened. It wasn’t an environment where anything goes, but sometimes the standards did.

Airstrip standards were always a challenge to maintain, and sometimes they slipped. Lagubang was a perched airstrip. If you landed short, the nose of the airplane would penetrate straight into the drop-off that preceded the threshold. And then there was a dogleg that had to be negotiated after touchdown, with the tailwheel slightly off the surface. Things grow quickly in the jungle. What had been a clear approach had become obstructed by encroaching tropical growth, forcing our touchdown point farther up the airstrip, conveniently beyond the dogleg. Not having to make that turn on a rain-soaked surface was a bit of a relief. And it happened gradually, so we got used to giving up more and more runway surface, each new touchdown point becoming the new standard.

On one pleasant flight near the top of the descent point, I noticed the altitude was 100 feet low, and my first thought was, “So what?” Then we began our descent into the 730-foot Bitogen airstrip. It was on a slope; you landed uphill, which made it easy to get stopped but also pushed the no-go point well before touchdown. It had terrain on all sides; it was narrow with village houses on both sides and the kids, pigs, and dogs were free to roam; there was no weather reporting other than a scraggly windsock; it had a rough, patchy surface; and there was no provision to make repairs. Now that’s aviation as it was meant to be!

On descent into that unforgiving strip, my safety officer’s words came to mind when I caught myself hunching forward in the seat, wiping the constant flow of sweat from my hands. That’s when it dawned on me that if I couldn’t hold my altitude within commercial pilot standards when all there was to be done was to fly straight and level in smooth air, it was arrogant—and dangerous—to think that I could consistently and predictably make an approach and landing to that airstrip, holding airspeed on final within two knots and touching down within a 20-foot zone.

Self-disciplined aviation applies though all levels of an organization. Leadership needs to set the example and execute on the standards. Leadership needed to say no to the deteriorating airstrip conditions at Lagubang, which intersected with an airman who needed to say no to becoming casual toward airspeed control on final. Every time an individual in an aviation organization operates with less-than-sterling flight discipline—and gets away with it—they collectively move closer to an accident.

How will you fly? How will you fly when no one is watching and you know you can get away with it? No SOP, no ATC, no FARs, and no chief pilot will take you as far as professional self-discipline will; it’s a maximum-effort maneuver.

Dan Gleason, of Bridgewater, Virginia, is an ATP and CFI-A. He has flown more than 10,000 hours and is type rated in the Beechcraft Super King Air, Bombardier Dash 8, and Douglas DC-3.

Digital Extra: Hear this and other original “Never Again” stories as podcasts every month on iTunes and download audio files free.

Illustration by James Carey