Make any mention of thunderstorms, and there are many pilots who simply stay on the ground until any hint of convection has passed. That strategy is safe enough, but it certainly curtails flying activity in the warmer months. So what’s a good middle path between cowering on the ground and making the best of a cross-country when a chance of convection exists? Yes, you can safely navigate certain convective environments, but only if you strictly adhere to some proven principles. Here are the main guidelines.

Study the weather pattern. This should include a review of both the synoptic, “big picture” view of highs, lows, and fronts, as well as the smaller-scale vital details included in TAFs and other briefing elements. Perhaps the best advance notice of thunderstorms can be found on the Storm Prediction Center’s website. Click on “Convective Outlooks” to see the areas currently expected to have thunderstorms, plus outlooks for the next seven days. The outlooks also give probabilities.

Another website posts area forecast discussions that also help flesh out the general situation. Bear in mind that most thunderstorms happen along frontal zones, and in the warm sector of a frontal system, which is the zone between the warm front and the cold front. That’s where warm, moist air lives. A preflight check of Nexrad radar imagery also is a must. Have thunderstorms along your proposed route already begun? Then it’s time to take a hard look at a go/no-go decision.

Pay attention to your instincts. Nervous? Unsure of the situation? Does any information in your preflight briefing make you uneasy? Perhaps you don’t have much experience flying in evolving weather situations, or you don’t have an instrument rating, or something just doesn’t inspire confidence. This is your good judgment talking. The best option may be to call off the flight and wait for a better day.

Take off early. In thunderstorm season, I get my briefings and head to the airport by 6 a.m. By then I will have seen the latest weather data, be ready to launch well before the heat of the day triggers any convection, and be at my destination before afternoon temperatures hit their maximum values. I make a last-minute weather check right before departure, hoping to see any late updates from the Storm Prediction Center, plus radar maps, airmets, and sigmets. The Lockeed Martin website (www.1800wxbrief) can be set up to send you messages concerning adverse weather as soon as they’re posted, so the smartphone can get a workout right before takeoff.

Stay visual. I think we all should know that the best summer flying strategy is to stay visual and remain well clear of any building cumulus clouds. That goes for low-time pilots as well as high-time, instrument-rated pilots. A climb to on-top conditions above any lower, scattered-to-broken layer of clouds is a great strategy. If you can stay on top you’ll be in a good position to spot any distant cumulus buildups, should they occur. Whatever you do, don’t enter clouds in an area of actively growing cumulus. The standard rule is to avoid any buildups by at least 20 nautical miles. That distance may be difficult to judge from the cockpit, but you get the idea: Steer well clear, whether you’re on a VFR or IFR flight plan. You say a barrier of towering cumulus is blocking your path, its sharply defined tops building to altitudes your airplane has no chance of topping? Then turn around or otherwise divert to cloud-free conditions—and maybe a precautionary landing, if clouds begin building all around you. Descend through any breaks if there’s a cloud layer below you, and don’t be afraid to ask ATC for help in altering your route.

Use onboard Nexrad imagery for strategic, not tactical, avoidance. Many pilots fly with datalinked or FIS-B radar imagery. Seeing the intensity, shape, extent, and movement of any storm cells is a valuable asset, no doubt about it. You want to avoid any lines, clusters, bow echoes, hook-shaped echoes, pendant-shaped echoes, echoes with scalloped edges, and echoes with steep precipitation contours. But it’s important to understand that the image you see in the cockpit can be up to 10 to 15 minutes old. It takes time for the service providers to obtain, render, and transmit imagery, so you may be closer to that hook echo (a signature for the circulation around a tornado) than the distance shown on your display screen. The moral: Use your radar imagery for wide-berth navigation around any storm cells.

Never attempt to “shoot the gap” between storm cells, lines, or clusters. This is a corollary to the rule just mentioned. It’s tempting, but don’t use radar imagery to weave your way around and/or through any precipitation echoes associated with convection. You could stumble into a deadly cell. The same advice applies to steering visually between gaps in cumulus buildups. That gap may seem like a good way through a line of buildups—until the gap fills in, and you find yourself flying on instruments in chaotic turbulence. Or you may think that by flying visually around a buildup you’ll be rewarded with blue skies, and the knowledge that you’ve safely traversed the last of a series of building cumulus. But let’s say that after going around that buildup you find yourself instead facing even more buildups, densely packed together, and presenting no way to fly on visually. Radar imagery may not help, because it only “sees” precipitation, or clouds with large water droplets. And besides, its information is old, and can trick you into flying into worse weather. You’ve lost sight of the biggest buildups, and therefore the most dangerous storm cells. This is where ATC can help you steer your way away from the most dangerous activity.

Don’t try to beat a storm to an airport. Here’s the setting for another dangerous temptation: your destination airport is maybe 20 nm ahead, you’ve been staying visual around clouds that are steadily darkening, and your datalink weather display is showing a bright red line of precipitation, chock full of lightning. It’s heading right for your destination. You want the flight to be over. You think you can beat the storm to the airport. What to do? Divert to an airport with a less-exciting environment? Or run the risk of instant IMC in heavy precipitation, significant turbulence, wind shear, and up- and downdrafts—all while flying close to the ground and desperately maneuvering for the active runway’s final approach course? I think we know your answer.

If there’s a moral here, it’s a simple one: Always make sure you’ll be flying into improving conditions.

Email [email protected]

Website of the month

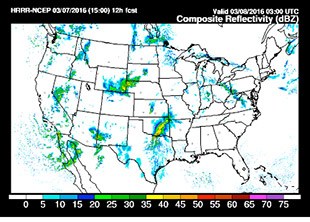

The Earth System Research Laboratory’s High-Resolution Rapid-Refresh (HRRR) model predicts radar returns out to 12 hours into the future. You can use it for advisory purposes; although the model has been declared operational, the “experimental” label still appears on some pages. The model updates hourly using radar data collected every 15 minutes. Visit the website and up pops a list of products along the left side of a chart. Across the top are the valid times for the forecast products. The products are pretty arcane, and intended for use by meteorologists, but by clicking on the “composite reflectivity” line’s forecast valid times (consult the line above it for the corresponding days’ valid UTC times) you can see the model’s ideas of what the radar returns should look like later in the day. At the very top of the page, where it says “domain,” you can select and zoom in on various regions of the United States. As I write this, it’s 18Z on March 7, 2016. The model above shows the HRRR’s idea of what the radar returns will look like at 03Z on March 8.

The Earth System Research Laboratory’s High-Resolution Rapid-Refresh (HRRR) model predicts radar returns out to 12 hours into the future. You can use it for advisory purposes; although the model has been declared operational, the “experimental” label still appears on some pages. The model updates hourly using radar data collected every 15 minutes. Visit the website and up pops a list of products along the left side of a chart. Across the top are the valid times for the forecast products. The products are pretty arcane, and intended for use by meteorologists, but by clicking on the “composite reflectivity” line’s forecast valid times (consult the line above it for the corresponding days’ valid UTC times) you can see the model’s ideas of what the radar returns should look like later in the day. At the very top of the page, where it says “domain,” you can select and zoom in on various regions of the United States. As I write this, it’s 18Z on March 7, 2016. The model above shows the HRRR’s idea of what the radar returns will look like at 03Z on March 8.