Paratroopers tend to regard airplanes as good for takeoffs only. So it was no surprise that Sgt. Joshua Ben, a youthful, former cavalry scout in the 82nd Airborne Division, cast a wary eye on AOPA’s 2009 Sweepstakes Let’s Go Flying SR22 before boarding it at Florida’s Orlando Executive Airport.

Paratroopers tend to regard airplanes as good for takeoffs only. So it was no surprise that Sgt. Joshua Ben, a youthful, former cavalry scout in the 82nd Airborne Division, cast a wary eye on AOPA’s 2009 Sweepstakes Let’s Go Flying SR22 before boarding it at Florida’s Orlando Executive Airport.

Ben, 22, an Afghanistan combat veteran, won a Bronze Star and Purple Heart there in 2007 after losing his right leg in an ambush. He’s in the process of moving from the U.S. Army’s Walter Reed Hospital in Washington, D.C., to Orlando where he’ll become a full-time student at the University of Central Florida in the fall. But on this warm June night, he needed to return to Walter Reed for some additional medical treatment—and that’s where the Let’s Go Flying SR22 came in.

The Veterans’ Airlift Command, a group founded to link general aviation volunteers with wounded veterans in need of transportation, put us together via the Internet. Ben and I met at the Showalter Aviation terminal, and I gave him a quick introduction to the Let’s Go Flying SR22.

“I’ve jumped out of C-130s and C-17s before, but I’ve never flown in anything quite like this,” he said.

When I told Ben that our aircraft was equipped with a ballistic parachute that could bring the entire aircraft down safely in an emergency, he warmed to the idea immediately.

Climbing up the step and onto the wing was no problem for the compact, square-jawed soldier with the athletic build, and he quickly eased his body into the right seat. Getting his prosthetic leg inside the airplane, however, required a trick that only a modern amputee would know. Ben pushed a button on his high-tech leg that allowed him to rotate the knee forward and fold it like a pocketknife. He was soon strapped in and we were taxiing to Runway 7 for departure on a marathon five-hour flight to Frederick, Md., AOPA’s headquarters (about 40 miles from Walter Reed).

It was already 9 p.m., and the sun had just disappeared as the Let’s Go Flying SR22 got off the ground.

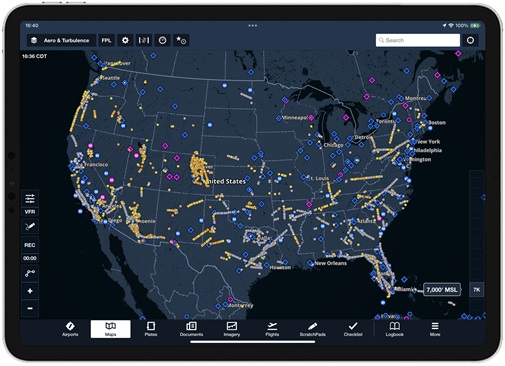

Ben had flown in a Cessna 172 once as a young teen near his family’s home in Columbia, Mo. He asked a few questions about the futuristic, glass-panel SR22, and caught on to the GPS navigation system immediately. A moving map showed our route would take us over Jacksonville, Fla., and Savannah, Ga., then inland over the Carolinas and Virginia to Maryland.

Level at 11,000 feet and 160 KTAS with the engine using 11.4 gallons an hour, the Avidyne Entegra avionics system showed that we’d arrive at our destination with nearly two hours of fuel remaining, despite a 20-knot headwind.

“Once you take off, it looks like there’s not much to do until it’s time to land,” Ben said.

Even though not required by regulation, we strapped on the clear nose hoses from a portable, two-place Mountain High oxygen system. Ben had spent 12 months at high elevations in Afghanistan before being wounded in October 2007, and he said he was beginning to recognize the physiological effects: colors on the moving map were getting less vibrant, and the small numbers on the screen were blurry. The oxygen cleared that up right away.

We had originally planned to make the flight the following day—but a forecast calling for violent weather prodded us to move up our departure time. The XM Weather on the Avidyne multifunction display showed monstrous thunderstorms in the Ohio Valley, but we were scheduled to arrive at our Mid-Atlantic destination well before the nasty weather.

Ben plans to study forensic science in preparation for a law enforcement career. It’s a big change from military life, and one he didn’t plan for before being wounded.

The Veterans Airlift Command provides free air transportation to wounded warriors, veterans and their families for medical and other compassionate purposes through a national network of volunteer aircraft owners and pilots.

The Veterans Airlift Command provides free air transportation to wounded warriors, veterans and their families for medical and other compassionate purposes through a national network of volunteer aircraft owners and pilots.

While serving as a gunner atop an armored Humvee, Ben and his platoon were ambushed on a narrow road by scores, possibly hundreds, of Taliban fighters. A dozen U.S. soldiers including Ben were wounded in the attack. A rocket-propelled grenade penetrated the side of his vehicle and wrecked his right leg in an instant. It happened so fast, he said, that he felt no pain at the time. Ben’s body armor protected him from most of the bullets that struck him, but one pierced his abdomen. Fortunately, it didn’t damage any organs, and doctors were able to remove the bullet during surgery. Ben, the future forensic scientist, keeps the nearly perfectly preserved AK-47 round in a specimen jar at home.

Ben credits a pair of A-10 Thunderbolt pilots for helping save him and his fellow soldiers with well-timed strafing passes.

“The sound of those Gatling guns was like music to us,” he said. “No one who hears them that close ever forgets the sound.”

Ben reclined his seat and slept for parts of our marathon SR22 flight. I was a poor host with few snacks or beverages to offer. Ben declined everything but a half stick of Doublemint gum.

The flight was the Let’s Go Flying SR22’s first in actual darkness since its new Forward Vision infrared camera system was installed at Lancaster Avionics, and it worked beautifully. There was little to see at altitude except a few scattered clouds. But as we descended over the Catoctin Mountains, the image on the glareshield-mounted, pop-up screen clearly showed the Catoctin’s curvy contours.

And on an ILS approach to Runway 23 at Frederick with visibility reported as four miles in mist, the lone obstacles—a pair of grain silos a mile from the threshold—showed up as bright as daylight.

“Just like NVGs,” Ben said, referring to the night vision goggles U.S. soldiers commonly wear in the field.

We tied the airplane down on the vacant ramp and loaded our bags in my car. Ben spent what remained of that night in our guest room, and my wife and two kids, ages 10 and 13, were excited to meet him at breakfast. Ben gave my son a few skateboarding tips before we began the hour-long drive to Washington, D.C.

The drive turned out to be the scariest part of our entire trip as the storms we had avoided with our early departure finally caught up with us.

“I’m glad we’re not flying through this,” Ben said during a cloudburst on Interstate 270.

Ben guided me among the winding roads at Walter Reed and soon had us at Malogne House, the temporary home of America’s wounded warriors as they remake themselves for the next phases of their interrupted lives. It’s a place of indescribable tragedy and triumph, and Ben appeared instantly at home among his brave fellows there.

As a member of the GA community, it’s a privilege to use the mobility we so enjoy on behalf of a young man who has made such a terrible sacrifice for his country.