Avionics: The iPad-centric cockpit

Behold the power of the tablet

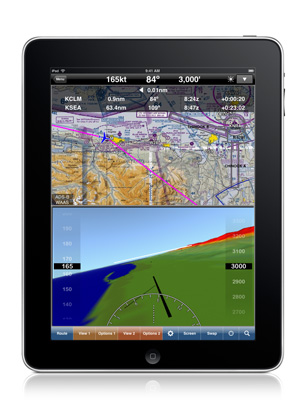

When connected to an AHRS, the iPad is capable of displaying GPS-based synthetic vision in a split-screen mode (left) or full-screen landscape view (below) or portrait view (shown here on Hilton Software’s WingX Pro7). Aviation software developers are racing to provide applications aimed computers indispensible to GA pilots.

In less than one year, the iPad has been transformed from a weight-and-balance calculator to a pre-flight planner, to an onboard electronic flight bag with charts, checklists, and instrument approach plates.

Now, aviation software developer Hilton Software also has made the iPad into a colorful flight display that graphically shows GPS-based synthetic vision, terrain, and obstacles. And Aspen Avionics and a growing list of partners are about to expand the iPad into a flight management system (FMS) capable of working in tandem with FAA-certified avionics to modify flight plans, tune radios, collect engine data, and record logbook information wirelessly. FreeFlight Systems and other firms are developing their own certified and noncertified receivers to enable the iPad to display ADS-B “In” features such as real-time traffic and subscription-free weather.

ForeFlight was the first to make the iPad an essential piece of equipment for many general aviation pilots flying airplanes ranging from Light Sport aircraft to jets, and backers say GA cockpits are likely to become even more iPad-centric in the future.

Hilton Software founder Hilton Goldstein said iPads are showing tremendous potential to lower the cost of flying. In the Light Sport category, for example, which is limited to day VFR flying, an iPad (or two) can take the place of traditional avionics and still provide high-end features such as a moving map, engine monitor, and GPS-based synthetic vision.

“The cost of avionics can make up 10 or 15 percent of the total cost of a new Light Sport aircraft,” he said. “The iPad can lower those figures dramatically.”

Flight planning software that compares fuel prices across regions can save pilots money at the pump. And chart and approach plate subscriptions that update automatically and cost less than $100 a year are a huge savings over traditional paper charts. Free cockpit weather via ADS-B “In” also has the potential to allow pilots to avoid subscription fees for satellite weather services.

Software developers say they are hard at work designing additional features they claim will make the iPad and other tablets indispensable to GA pilots.

But are there limits to the cockpit tasks the iPad can, or should, do? Even iPad software designers say the versatile devices aren’t a replacement for FAA-certified avionics.

“Synthetic vision on the iPad isn’t a primary navigation tool and never will be,” Goldstein said. “It’s meant to enhance a pilot’s situational awareness only.”

Unlike the FAA-certified synthetic vision products offered on built-in primary flight displays, for example, the baseline WingX Pro7 offering for the iPad isn’t connected to an air data computer, or the aircraft pitot-static system, so it shows groundspeed (not indicated airspeed) and doesn’t show aircraft pitch or roll. The WingX Pro7 version shows a horizontal view of the outside world based on GPS-derived position and altitude only (unless connected to an attitude heading reference system, or AHRS, and then it shows pitch, roll, and indicated airspeed).

But others are already jumping in to offer low-cost methods of making the iPad a full-featured flight display.

Levil Technology, a hardware firm based in Oviedo, Florida, makes and sells a miniature, solid-state AHRS compatible with iPads and iPhones that allows those devices to instantly display heading and roll information (as well as indicated airspeed and altitude). Levil unveiled a $795 AHRS at EAA AirVenture 2011 that weighs just five ounces, and iPad owners snapped them up. On the second day of the show, the first 25 units were gone, and company founder Ruben Leon was hurrying to make more.

“Demand for these AHRS units among iPad owners is very strong,” he said. “Much stronger, in fact, than I had anticipated.”

Since the AHRS units connect to portable devices, they can’t be certified for IFR flight. But Leon said the miniature units are made from many of the same components that go into FAA-certified avionics, and they are capable of providing valuable back-up information in case the primary instrumentation fails. Also, owners and pilots of certified airplanes may opt for synthetic vision on tablet computers as an alternative to upgrading to glass panels—or buying synthetic vision for the glass panels they already own.

Software developers say they are hard at work designing additional features they claim will make the iPad and other tablets indispensable to GA pilots. In addition to preflight planning and in-flight charting, the tablets can record flight and engine performance data for post-flight evaluation.

The iPad and similar tablets have some built-in advantages over portable aviation GPS units. Tablet screens, for example, are far larger than other portable moving-map displays, provide higher resolution, and have much longer battery life. Also, because they are produced on a massive scale, unit prices are significantly lower.

Tablets are far from perfect for aviation use, however. They are sensitive to heat and cold, their oversized touch screens can be troublesome in turbulence or when wearing gloves, and they reflect glare in direct sunlight. Still, the tablet computers’ reliable operating systems and intuitive user interfaces—as well as their rapid adoption by pilots around the world—have convinced aviation software designers and some avionics manufacturers that powerful tablets should be the bridge to a wide variety of FAA-certified, panel-mount avionics.

Pilots soon will be able to use tablet computers to plan trips, file flight plans, download those plans to panel-mount avionics, update routes in flight, watch for traffic and changing weather, and record flight times and equipment anomalies after landing.

“We will add a highway-in-the-sky feature as well as traffic and many airspace features,” said Goldstein of Hilton Software. “We’re a serious company with serious features. We’re providing ways for the iPad to supplement panel systems and allow pilots to quickly access information and change routings on the larger screen and then program their certified counterparts.”

Aspen Avionics envisions a wireless “connected panel” in which avionics manufacturers and software designers use an open standard that allows two-way communication between tablets and panel-mounted avionics. Aspen has announced a broad series of partnerships with a variety of hardware and software firms aimed at creating an open-ended series of new aviation applications that can be controlled through tablet computers.

“The power of the tablet is that it can become the gateway to the full range of FAA-certified avionics,” said John Uczekaj, Aspen president and CEO. “Everything that pilots do manually now can be done automatically through tablet computers. The tablets will be useful before, during, and

after each flight—and they can help take avionics integration to the next level.”

Uczekaj recently posted on his blog, “When the history of general aviation is written, 2011 will be the year of the iPad.”

Email the author at [email protected].