IFR Fix: AOA and IMC

When a Cessna 182T single-engine airplane crashed a mile short of a Texas airport in 1.5-mile visibility, broken clouds at 800 feet, a 1,300-foot overcast, and "heavy drizzle," the impact occurred, investigators said, “in a nose-low attitude, consistent with a stall/spin.”

The probable cause of the May 2013 accident in Fredericksburg, Texas, was the 176-hour instrument-rated private pilot’s “failure to maintain airspeed while transitioning from instrument to visual flight,” the National Transportation Safety Board concluded.

“It is likely that the pilot, during his transition from instrument to visual flight while still in instrument conditions, did not ensure that the airplane maintained adequate airspeed,” the NTSB said.

A useful discipline for instrument flight is to fly on the gauges if necessary, or visually if possible, but not both. Real-life scenarios to practice this art don’t often come along. But go visual too soon and a hasty return to the gauges can induce errors or vertigo.

Some instrument instructors teach remaining on the gauges until the descent has reached minimums when ceilings are low enough to make the approach a close one. (Do you practice this technique? How do you manage such scenarios?)

Accidents attributed to loss of control have been put in focus for general aviation, with education and technological solutions all potentially contributing to flight safety.

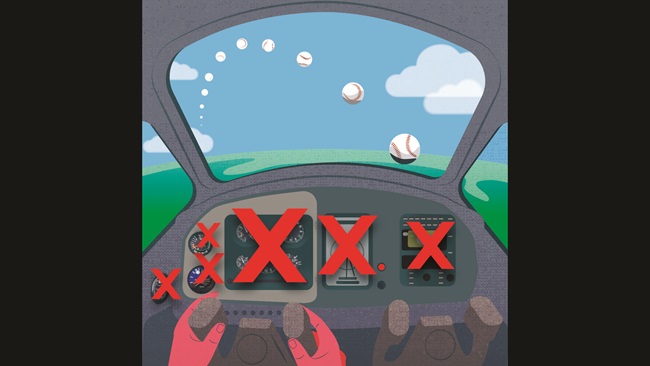

With rules recently relaxed for adding non-required instrumentation to GA aircraft instrument panels—long advocated by AOPA—pilots can consider enhancements such as the angle of attack (AOA) indicator, designed to “determine the current AOA, and provide a visual image of the proximity to the critical AOA,” explains the FAA’s Airplane Flying Handbook.

Any system only serves as intended if pilots learn its pluses and minuses. A 2015 addendum to the Instrument Flying Handbook notes that an AOA's effectiveness depends on factors including calibration techniques; probes or vanes not being heated; indicator type; flap setting; and wing contamination.

No device substitutes for situational awareness acquired by practicing scenario-specific skills. That’s reason enough to put review of IFR-to-VFR transition scenarios on the task list for your next proficiency flight.