Broadcast engineer checks towers with drone

Caution and risk mitigation required

The director of engineering for a Colorado-based company that operates radio stations around the country has become an advocate within his industry for drones as tools that save dollars and reduce the risks taken by tower climbers. Private pilot and AOPA member Cris Alexander also gives unmanned aircraft partial credit for motivating his return to manned aviation.

Alexander is responsible for supervising the maintenance and operation of dozens of radio towers around the country, having led the engineering department of Crawford Broadcasting Co. since 1984. He has for decades presided over the construction, modification, and maintenance of radio towers ranging from 375 feet to 1,400 feet tall—towers fitted with antennas that today deliver a total of 36 distinct signals to AM and FM radios in seven states.

“I don’t think that any tower service company worth their salt has an excuse anymore for not doing this,” Alexander said. The climbing associated with even a relatively simple task can cost the tower operator $1,500, coincidentally also the cost of a DJI Phantom 4 Pro with a battery and controller. With seven Denver-area towers flown to date, some more than once, “the drone that we have has already paid for itself a couple of times, because it saved climbs.”

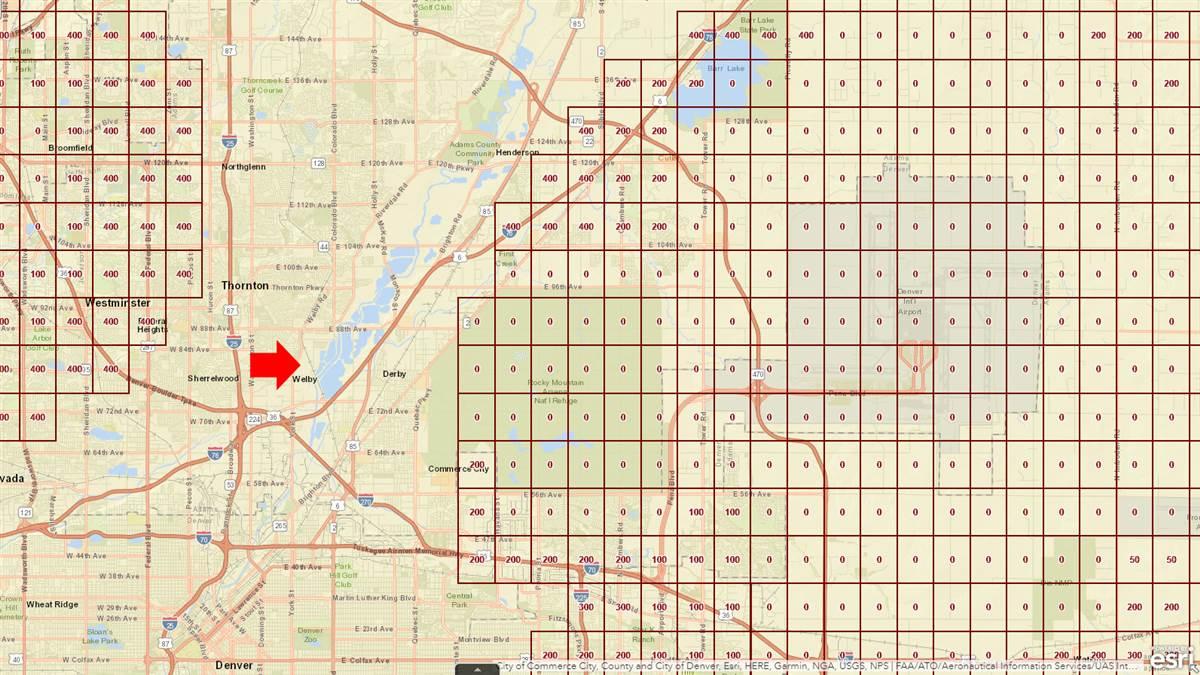

Alexander is able to put his drone to work in part because Part 107 allows for flights above 400 feet, without a waiver, as long as the drone remains within 400 feet of a structure. Keeping the drone in sight and maintaining situational awareness in close proximity to structures is often a bigger challenge for high-altitude operations than airspace: Alexander learned on Feb. 14 that a Phantom can lose a significant portion of two propellers and still fly. An inopportune wind gust blew the quadcopter into the tower as Alexander approached, and his bird was not above the top of the structure as he had thought. The Phantom's built-in obstacle avoidance did not respond quickly enough to compensate for the wind gust.

“I was several hundred feet away and didn’t know it had actually hit the tower—my only indication of a problem was the beeping of the proximity warning, and I immediately backed off. I got the photo and then flew back to the launch point,” Alexander wrote in an email. He noticed the Phantom was making an unusual “clattering” noise as it approached for landing, but he recovered the quadcopter without incident, only noticing when he got back to the car that up to half of the airfoil was missing from two of the four propellers. “Amazingly, the Phantom was able to fly back home even with that damage! I was impressed!”

Alexander wrote that he learned four specific lessons from the experience: Gusty winds require extra vigilance and caution on approaching the tower, including greater initial standoff distance; changes in ground elevation at the tower bases must be accounted for when estimating the drone’s altitude relative to the tower; the aircraft should be flown on the leeward side of objects when possible; and depth perception degrades significantly when the aircraft, pilot, and tower are aligned. “This, along with failing to account for the ground elevation change, was what put me way, way too close to the tower in the first place.”

Most of the inspection work Alexander has done with his drone to date has been free of incidents, despite the many challenges and unknowns involved. As a private pilot, he has employed a generally cautious approach.

The height of broadcast towers and the power of the electromagnetic fields the antennas mounted on those towers create require a rigorous approach to risk mitigation, and just how much radio frequency interference a drone can stand remains to be seen.

“That is a great unknown, and we’re dealing with different frequencies,” Alexander said. The towers he is responsible for as the company’s chief engineer can blast out up to 50,000 watts of AM signal, along with powerful FM transmissions, and microwave signals are used to connect the tower and transmitter with the broadcast studio, usually in a different location. Alexander said that the microwave signals are tightly focused and easily avoided by not flying in front of those antennas. FM antennas also blast out a torrent of electromagnetic waves, though the potential danger zone is largely within the antenna’s aperture. FM stations in major markets typically broadcast from two towers, allowing one to be powered down for inspection without taking the station off the air. Reducing the transmission power is also a solution on the AM side: “When I’m flying, I don’t leave that AM at 50,000 watts, I turn that down to about 1,500,” Alexander said.

Even with the radio signal power reduced, Alexander has grown used to seeing an on-screen caution message during his tower flights. Just as it was a surprise to Alexander that a Phantom can still fly in gusty winds with two of its propellers chopped in half, it remains an unknown just what the limit on radio frequency interference actually is. He suggested that someone willing to risk losing a drone for discovery might help his industry figure that out. More than 40 years of broadcast engineering have taught Alexander that there’s no reliable way to predict without real-world testing how any electronic device will behave in the RF-saturated environment around a broadcast tower. Considering the other tools of the trade, more expensive devices are not necessarily more robust, and much depends on the design and configuration of circuits and components. “There’s just no rhyme or reason to the way a device will react to a high-RF field.”

Alexander is also the technical editor of Radio World Engineering Extra magazine, an industry trade publication, and recently published an article touting the value of drones as tools for broadcast engineers. While a small quadcopter is not going to replace an anti-collision light bulb or hang a new antenna, it can save several of the tower climbs associated with those tasks. Alexander said the images captured by a drone can be used to plan and design installations, in addition to spotting structural faults. The drone’s camera can also give an engineer on the ground a view of equipment indicator lights, and reveal anomalies such as missing or broken lightning rods that are not visible from the ground.

Across the industry, climbers are sometimes called on to scale towers with very little information about the structure’s condition or history, and a quick drone survey can spot a potential safety issue before a climber is at risk, Alexander noted.

Alexander said the low cost of drone inspections also means they can be done at higher frequency, enabling further savings through preventative and proactive maintenance. He has personally found three broken or damaged lightning rods in just a few flights so far. He said he has assigned three of his staff engineers to train and obtain their own remote pilot certificates, and expects that smaller operations including mom-and-pop radio stations may benefit from hiring remote pilots from outside their company to fly the towers. “I think there’s a little room for both (approaches).”

He said Part 107 pilots interested in providing this service might want to start by contacting tower maintenance contractors in their area, or the local chapter of the Society of Broadcast Engineers, whose members are also the end users of tower inspection images and video.

Alexander may at some point opt for a bigger drone. He said that a drone flying near the top of a 400-foot tower can be hard to spot, and it remains to be seen what solutions might work for the taller structures.

“Our guys in Alabama, they’re going to have to figure that out,” Alexander said. A larger drone might be the answer, or additional strobe lights, or additional observers. “We’re just going to have to feel our way.”

His enthusiasm for the technology remains high notwithstanding any limitations encountered so far, and Alexander said the relative ease of obtaining a remote pilot certificate for a pilot who already holds a Part 61 certificate with a current flight review factored into his decision to return to the cockpit last year after a 25-year hiatus.

“Part of the reason that I got back into that, I wanted to get current was so that I could get my (remote pilot certificate) without having to test for it,” Alexander said. “It worked out great.”

Alexander said that bringing manned aviation experience to the unmanned world has other advantages, both for the individual and the industry, including the training in risk mitigation and anticipation that comes with learning to fly aircraft from the inside, particularly as new missions are explored, such as the challenging environment of a broadcast tower complex.

“I think it’s good for aviation people to be doing some of this stuff,” Alexander said.

“Although, I’m the only guy in the company right now with a sUAS certificate,” he added, with a chuckle: “Darn the bad luck, I’m the guy who has to fly the drones around.”