Such fine sights to see

Winslow, Arizona

Many pilots fly to Winslow-Lindbergh Regional Airport in central Arizona just for the enchiladas at E and O Kitchen, the family-run Sonoran/Chihuahua-style Mexican restaurant next door to Wiseman Aviation. You also might attend the High Desert Fly-In, for airplanes, history, music, dancing, and food. But “slow down and take a look,” stay a while, and see what wonders Winslow has to offer.

Who can resist “standin’ on a corner in Winslow, Arizona” just like the Eagles sang in the mega-hit Take It Easy? About 100,000 people do it every year, so you never know who you’ll meet. If you ask me, the bronze statue of a 1970s-era troubadour with his guitar at Standin’ on the Corner Park bears a certain resemblance to Jackson Browne, who wrote the song with Glenn Frey. The “flat-bed Ford” is there too.

La Posada’s new ownership also ignited a burgeoning art scene that’s helping transform Winslow into a hip, edgy cultural center. Iconic L.A. artist Ed Ruscha is a regular visitor who cites Winslow as one of his top 10 American towns. Somehow during all the renovation work at La Posada, Dan Lutzick, a sculptor and partner in the hotel, found time to buy and transform the old Babbitt Brothers department store into the Snowdrift Art Space. Dan lives there with his wife Ann-Mary, director of the Old Trails Museum, and their dogs. Many of Lutzick’s sculptures are made of layers of cut-out wood and remind me of kachinas, with a Day-of-the-Dead twist to them; free guided tours are by appointment. The Old Trails Museum is filled with artifacts and fossils from the local area. The Winslow Arizona Chamber of Commerce occupies the former Lorenzo Hubbell Trading Post. It’s almost like a museum, with all the historic elements left intact.

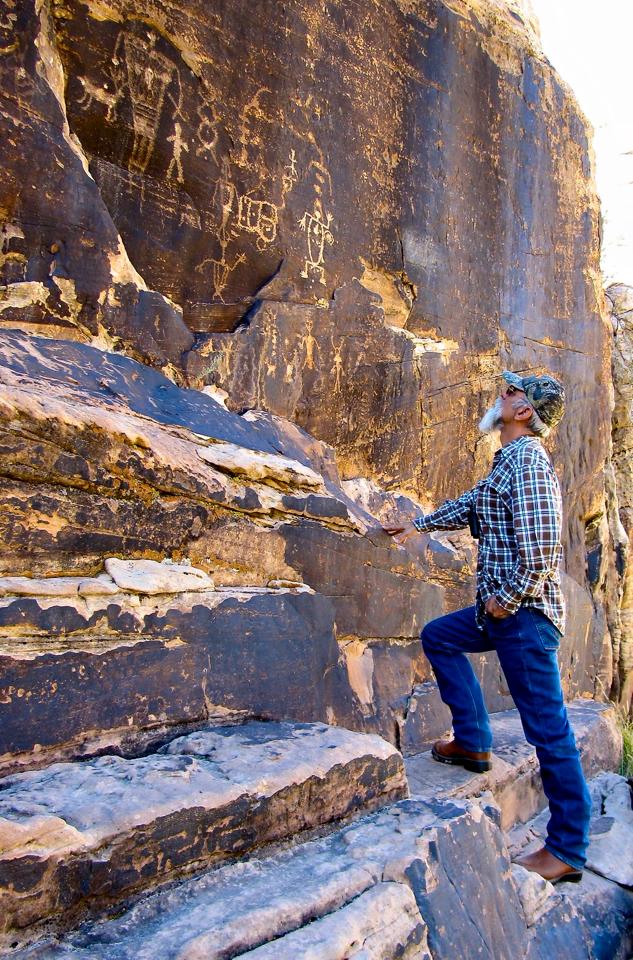

Hiking enthusiasts will want to head just north of town to Homolovi State Park, where you can walk the trails around archaeological sites and ponder the petroglyphs of the Hopi ancestors that lived in the region until AD 1400. Petrified Forest National Park is an easy, one-day loop trip from Winslow. Giant logs lie as though they had just fallen. They look like wood, but are now stone, mostly fossilized specimens of Araucarioxylon arizonicum, massive extinct conifers that grew here along rivers during the Late Triassic period, about 211–218 million years ago. My favorite secret in this area is Rock Art Ranch, off I-40 between Winslow and Holbrook, which contains some of the Southwest’s most extensive petroglyph sites. Brantley Baird, a 75-ish cowboy who still raises cattle and bison, will share secret spots and museum-quality ancient pottery he’s found on his property. Rock art covers the cliffs of Chevelon Canyon; pottery shards are strewn across the ground near unexcavated Native American pit houses; tours by reservation only.

Hopefully you’ll overfly Meteor Crater, 20 miles west of Winslow—the world’s best-preserved meteor impact site and almost a mile across. But you can visit on foot as well to view the crater, where Apollo astronauts trained and Starman was filmed. You’ll also see an Apollo test command module and a 1,406-pound meteorite found nearby, plus smaller, touchable meteorites. A theater shows a film that depicts the impact that occurred about 50,000 years ago. When you need to take it easy, fly in to Winslow. Pull up a chair and watch the trains pass as you relax with a margarita. Tune in to Winslow’s new art scene and turn on to the Turquoise Room’s fine Southwest cuisine. Soon you’ll be runnin’ down the road again, but you can always come back.

Share your favorite destination in the AOPA Hangar: Places to fly, things to do, where to eat!