'I just knew what to do'

Suderman loses prop, lands Pitts safely

Spencer Suderman was cruising over Southern California on April 27, on his way to Arizona for a crack at beating his own inverted flat spin world record, when the propeller departed his Pitts. The veteran instructor and airshow pilot spoke to AOPA about how training and experience proved crucial.

Suderman was about 10 minutes into his flight from Santa Paula Airport to Yuma, Arizona, cruising at 7,500 feet with VFR flight following when he noticed an unusual vibration.

Next, he eased back on the power, reducing from his customary 2,600 rpm cruise. A few minutes later, the vibration got worse, more obvious, attention-getting. He noted that Van Nuys Airport was a few miles off his right wing. Just as he was about to key the mic to inform ATC that he intended to divert to land at Van Nuys, there was a noise.

“Not a loud noise, just a ting,” Suderman recalled in a May 1 telephone interview. That “ting” was probably the sound of his departing propeller striking the cowling or fuselage. Then the engine began to race.

First, he flew, as he was taught, and teaches others Pitch down, reduce power, figure out where to head next. He saw a familiar set of runways and started a turn.

“Now I key the mic and declare an emergency,” Suderman recalled. LiveATC.net recorded the exchange, with Suderman announcing his intent to make an emergency landing at Whiteman Airport in Los Angeles, by now about 2 nautical miles ahead at 10 or 11 o’clock. (Listen to the edited LiveATC.net archive recording, shortened for time and to remove extraneous traffic.)

Suderman wanted airspeed, knowing that a prop-less Pitts could get difficult to control. He had altitude to burn. Being in the crowded Los Angeles airspace, there were airports all around, but also a crowd of buildings, cars, and people between them.

“I’m not worried about making the airport,” Suderman recalled. He was, however, worried about fire.

The propeller had cracked the oil cooler on departure, he would later learn, and the distinct odor of burning oil that filled his nostrils was caused by engine lubricant leaking onto the hot exhaust, though he had no way to know that in the moment. Pilots are trained to increase airspeed in response to in-flight fire, since the extra wind velocity might just put out a fire, and also because getting on the ground as quickly as possible becomes a priority.

The air traffic controller didn’t miss a beat after being told that “Pitts 781” was descending (somewhat rapidly) to make an emergency landing at Whiteman Airport:

“Pitts 781 roger, VFR descent approved and, ah, do you require any further assistance? Whiteman is 11 o’clock, a mile and a half.”

“Can you clear a path? I think my prop’s departed,” Suderman requested.

“781 Roger, and, ah, your VFR descent is approved to the field. Do you have the field in sight? Ah, low, and, ah it’s about two west of you. Or correction, two east of you, 781."

‘Time to think’

Suderman had a few things going for him in addition to being already in radio contact with ATC (for VFR flight following) when the trouble hit. He holds the Guinness World Record for consecutive inverted flat spins, and he’s also a flight instructor who practices what he preaches, including a more-is-better approach to altitude. He noted that it’s not uncommon for VFR traffic to transit Los Angeles airspace at lower altitude, and flying lower leaves fewer options, less time to think if, for example, your propeller suddenly falls off.

“I can say that without having to think about it… I just knew what to do,” Suderman recalled. "When you lose power, you put the nose down immediately. So that worked well.”

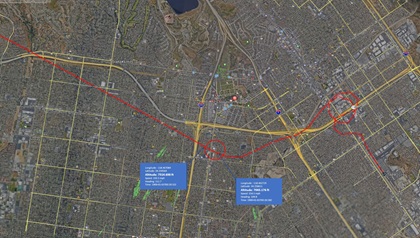

Some might make a beeline for the runway, even one that was nearly underneath the airplane. Suderman opted to aim for a point about a mile beyond the end of his chosen runway, and the GPS track and labeled satellite view that he compiled after the fact shows a slight turn to the north, overflying the interchange between the Golden State Freeway (Interstate 5) and the Ronald Reagan Freeway. Another advantage came into play: familiarity. Suderman had long ago earned his commercial pilot certificate and flight instructor certificate at Whiteman Airport, so he knew the neighborhood.

He knew he had to keep his speed and descent rate up. He knew bailing out was not an option, though he always wears his parachute. It doubles as a seat cushion, and Suderman can think of no good reason not to strap it on—even for what was supposed to be a boring, wings-level, cross-country flight.

“That thought of bailing went in and out of my head in about a microsecond,” Suderman said. He was extremely confident he had the runway made, and knew that an uncommanded Pitts had nowhere to crash without making injury or death on the ground highly probable, if not inevitable. Also, while the smell of burning anything will get any pilot’s attention, Suderman’s legs were not being burned by licking flames, so he took the time to circle about a mile out and keep his descent speed high but under control.

Suderman said having that extra altitude to work with was a huge advantage, one that he counsels every student to strive for: “Give yourself time to think about it and make the right decisions.”

Suderman announced his intention to make his emergency landing on Runway 12. (Pilots in such circumstances do not make requests of ATC, they announce what they’re going to do.)

“Pitts 781 affirmative, and, ah, you can proceed direct to the field, there’s nobody, ah, in the vicinity at the moment. Do you have the field?”

“I’m going to circle down.”

“Pitts 781 you are cleared to land Runway 12 or Runway 30. Winds calm at the field.”

Suderman did not respond. The controller asked another aircraft to relay the message that Pitts 781 in a very real way owned every inch of pavement at Whiteman Airport at that moment, and had two runways to choose from:

“Either runway at Whiteman is cleared for your landing, 781,” said the pilot of 172 Romeo Whiskey.

Suderman was coming in hot, but he knew he had a little more than 4,000 feet of runway to work with, nestled though it was in a crowded city.

“I’d rather come in a little hot… I could ground loop it, do anything,” Suderman recalled thinking. “I knew if I could at least get on the runway, I’d have a better chance of being OK… your other choices are very bad.”

He bled off energy with S-turns on final, then slipped in with right rudder and left aileron.

“I held that all the way down to the runway,” Suderman recalled. He touched down on all three wheels and “bounced a couple of times,” but kept the airplane tracking true and rolled to a stop, nearly making it to a convenient intersection. “I had to get out and push it the rest of the way.”

Suderman deadpanned, when asked how long it was before he took a deep breath: “Sunday morning.”

‘We don’t know what, yet’

Suderman said the reason for the propeller failure remains a mystery pending further investigation. The propeller’s whereabouts remain unknown. Los Angeles police were contacted by Whiteman tower controllers, who inquired if anyone had reported unusual objects falling from the sky, such as carbon fiber propeller blades, possibly attached to an aluminum hub. There have been no such reports, yet, that Suderman is aware of.

(Reviewing the GPS tracks and Google Earth, there is a Chase Bank at 9154 Sepulveda Boulevard, Los Angeles, next to a bowling alley. Somebody might want to pop up and check those roofs).

“Something happened … we don’t know what, yet,” Suderman said. “What everyone wants to get is the hub.”

Losing a propeller in flight is highly unusual. Suderman said his experience flying in unusual attitudes proved helpful, enabling him to size the situation up perhaps a little more quickly when things went south. His first moves, reducing power and pitching down, “that was just an instinct,” he recalled.

Suderman said he simulates engine failure at a lower altitude than many instructors, around 1,000 feet agl. “That’s when it’s really going to happen,” Suderman said, referring to the slightly more common scenario of power loss on takeoff. “I’m looking for the pilot to immediately push the nose down.”

He also wants his students to make use of flight following services, to never pass up a chance to talk to ATC. Being already on frequency allowed him to not only skip the formalities of announcing who he was, where he was, where he was going, and what was going on, he didn’t have to hunt for a frequency and dial it in, either. There wouldn’t have been time.

Suderman said bailing out might have been the choice to make had the propeller stuck with his airplane another 20 minutes or so, which would have put him out over the desert.

“Landing in the dirt in a Pitts is not a good idea. They tend to flip over,” Suderman explained. So the parachute might have come in handy had he not lost the prop over a familiar airport.

“Always give yourself options,” Suderman advises.

Suderman had already taken a break from flying airshows to focus on trying to break his own inverted flat spin record. He lives in Florida, now, and expects to return to the airshow circuit eventually. After he takes another shot at that record. And that’s after his crew tears down the engine and makes the needed repairs, and installs a new propeller. Doubtful the old one will be of much use, if it ever turns up.

“That’s going to take a bit of time to put all that back together,” Suderman said. “I believe I’ll get a Christmas present of being able to fly again.”