Balancing drone integration opportunity and risk

AOPA remains active, engaged

As the FAA considers allowing more freedom for drones to maneuver, AOPA urges the agency—and fellow members of the FAA Drone Advisory Committee (DAC)—not to expect manned aircraft to add new equipment to facilitate safe separation.

While AOPA continues to broadly support safe integration of drones, a troubling trend has emerged that could put AOPA at odds with some of those working to accelerate drone integration. To be clear, AOPA remains as enthusiastic as ever about the benefits that stand to be realized when small, unmanned aircraft are allowed to fly beyond line of sight for missions including package delivery, finding missing persons, and infrastructure inspection. However, a few of the remarks and proposals floated at the first 2020 meeting of the DAC, a gathering that included several newly appointed committee members, prompted concern.

“If we think about this sort of in the long term,” Player said at the February 27 DAC meeting, “what can we do to say ‘yes’ to technologies that would facilitate collaboration between manned and unmanned aircraft in the interest of safety? Could we work towards a technology solution, and maybe it’s not a single solution, but things like vehicle-to-vehicle technology, maybe it’s a transceiver, a traffic beacon, that reports the minimum information between aircraft to facilitate collision avoidance?”

This was not the first time that members of or advocates for the UAS industry suggested that life in the National Airspace System would be easier if every flying object could just be equipped with technology to electronically share location information. AOPA, which has participated in DAC meetings and similar conversations for years, has often noted that even if every manned aircraft operator were forced to buy equipment to broadcast, birds and bats will remain “noncooperative” no matter what.

“The UAS industry’s development of detect-and-avoid equipment for unmanned aircraft is still at a point where reliability, size and weight are significant challenges. However, these challenges cannot be a justification for imposing new costs and burdens on all other airspace users,” said AOPA Director of Regulatory Affairs Christopher Cooper.

Christian Ramsey, the president of uAvionix who joined the DAC a week before the February 27 meeting, worried aloud that the engineering challenges involved with enabling automated DAA, particularly for smaller unmanned aircraft, may prove insurmountable.

“There’s a real, it seems to me, concern out there that what’s on the market now isn’t going to get us where we need to be,” Ramsey said. “There really is a need for FAA to sort of help let us know where you see promise, so that we can direct our activities in certain areas.”

Jay Merkle, executive director of the FAA UAS Integration Office, responded:

“We are seeing a need to create a larger DAA framework, in that DAA is one term but we realize it applies in many ways, (and) many levels of performance,” Merkle said. “And we’re preparing to engage industry in a conversation of what does that framework look like and how can we best use it.”

Merkle continued: “We are committed to a performance-based standard approach, so any of the technologies that we would want to give people credit for, in terms of risk mitigation, we would like to see move towards industry-based, consensus standards. We do have some of those already, but they’re mostly focused on the large aircraft that can carry large systems and generate a tremendous amount of electricity, energy, so we’re seeing more promise in the solutions in DAA, both in electro-optical, and ADS-B In, and other technologies. We’re working with folks to establish what’s the right performance for the missions they’re going towards.”

While AOPA can be counted on to oppose mandating all aircraft operators equip with ADS-B or a similar technology to be electronically “seen” anywhere they may choose to fly, AOPA is promoting voluntary ADS-B equipage because it increases the safety margins and effectiveness of most existing DAA systems. The FAA is looking at Unmanned Traffic Management (UTM) participation by manned aircraft to be voluntary, per the new UTM ConOps 2.0. Creating a UTM framework has similar challenges as DAA in that there may be noncooperative traffic in UTM proposed airspace, but the FAA has been clear on this topic that manned aircraft need not expect any mandates.

Cooper and other staff members have worked with various DAC task groups to support other, more incremental and cost-effective advances in drone airspace access. One such group reported back to the DAC on February 27 various recommendations for the FAA to improve the Low Altitude Authorization and Notification (LAANC, pronounced “lance”) system that was launched in 2017 to automate the process of granting UAS operators access to controlled airspace.

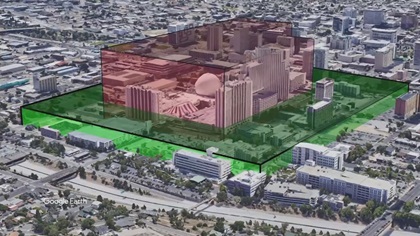

The current LAANC system began with a pilot program, and the DAC recommends doing the same with a new version that would quadruple the number of grid squares over and around airports that depict maximum altitudes where drone flights may be authorized by cutting their length and width in half. (Each existing grid square would be divided into four.) The task group assigned to look at LAANC improvements also presented consensus recommendations to assign the refinement of individual airport “grids” to a wider group led by local air traffic management staff (who largely created the original grids on their own) and including local operators of both manned and unmanned aircraft.

Additional drone-friendly airspace can be found around buildings and other obstacles, which define airspace that is unsafe for manned aircraft but that can be safely navigated by small UAS, the task group noted, all of which can be defined using data the FAA already has.

Unmanned aircraft certification was also discussed by the DAC, which met days before a March 4 deadline to submit public comments on a notice of proposed policy and request for comment on establishing a type certification process for unmanned aircraft by adapting existing regulatory mechanisms designed for other “special” types of aircraft. That policy notice, published February 3, only drew 65 comments, compared with the 53,036 comments submitted (including by AOPA) in response to the FAA’s proposed rulemaking for remote identification and tracking of drones.

Certifying unmanned aircraft according to performance-based standards may not galvanize the attention of the drone-flying public the way remote identification has, but it is nonetheless an important part of advancing the industry, AOPA noted in formal comments filed in response to that notice of aircraft certification policy.

“Having a pathway to ensure these aircraft are manufactured and standardized will help ensure an equivalent level of safety is maintained alongside incumbent aircraft and the general public,” Cooper wrote.

However, in much the same way that AOPA called on the FAA to ease the burdens on hobbyists and recreational users that its proposed remote ID system would create, Cooper wrote that the FAA should likewise exempt hobbyist-flown aircraft from certification requirements, even those that are larger than the 55-pound limit applied to Part 107 operations:

“These low-risk aircraft used for personal recreational purposes should not be subject to this policy. These aircraft, made of a diverse fleet of both kit and home-built designs, have operated safely in the NAS for decades under programs such as the Academy of Model Aeronautics’ Large Model Airplane Program,” Cooper wrote. “While these operations typically do not fall under 14 C.F.R. § 107, AOPA sees no persuasive reason, policy or legislative, that these types of aircraft should be subject to the 14 C.F.R. § 21 type certification process.”

Merkle noted during the DAC meeting that the public response to the FAA’s invitation to comment on certification was encouraging:

“The good news is, we are seeing significant positive response to the message that people need to get their aircraft certified,” Merkle said, noting that about 40 unmanned aircraft systems are currently seeking certification. “I feel very positive that aircraft certification and flight standards are important… we’re forming that bridge, and the good news is, everyone’s responding.”

The FAA posted video of the DAC meeting on YouTube in two parts: the first half of the meeting included FAA responses to previous DAC recommendations, and the second half featured new recommendations for the FAA to consider including LAANC refinement.