The day aviation stood still

20 years later

In that silence as we tried to understand the events of the day, many of us contemplated what the future might hold in an era when civilian airplanes had been turned into weapons of mass destruction. What sorts of restrictions might we face?

The situation looked grim in those first few days. Word spread that the terrorists had learned to fly at U.S. flight schools. Officials who didn’t understand the capabilities and limitations of general aviation airplanes felt threatened by the idea of “little airplanes” flitting about without any insight into who might be aboard and where they might be going.

The solution seemed to be either ground them all or, at a minimum, require them to be on IFR flight plans and under constant radar surveillance and radio communication. Flying over major cities and near primary Class B airports—forget about it. Flying VFR up the Hudson River corridor in New York City—not a chance, we feared.

Fortunately, and in large part because of the work of AOPA’s regulatory affairs staff, officials eased up on some of the restrictions within a few days for IFR flights. After many meetings to educate security officials, we eventually were allowed to fly VFR and even to once again fly in and around Class B airspace. Even the Hudson corridor was reopened—an opportunity years later for us to watch Freedom Tower grow from the ground up, fill the gaping hole in the Manhattan skyline once dominated by the World Trade Center twin towers.

Today, aside from the special flight rules area and flight restricted zone over the Washington, D.C., area, and some outdated and unneeded stadium TFRs, there are few airspace restrictions that have their roots in the 9/11 tragedy (see “President’s Position: Cherish Your Freedom To Fly,” p. 8). Flight schools and CFIs attempting to train foreign students face paperwork challenges, as do those students, but those who want to learn to fly in the United States can do so with minimal extra effort.

In this special section, we reflect on the 20 years since that fateful day, including comments from those who were in the air when aviation stopped; and those who have benefited from one of the brave airline pilots that day, and the story of the one lifesaving mission that wasn’t grounded amid the chaos. —Thomas B. Haines

GA under siege

Reflections

GA under siege

GA flight in the TFR, um ADIZ, er SFRA

By Peter A. Bedell

In the November 2001 issue of AOPA Pilot, I wrote about being stranded in Rolla, Missouri, with my family’s Beechcraft Baron while returning from an AOPA assignment in Wichita, Kansas (see “Where Were You? Grounded,” November 2001 AOPA Pilot). I was stranded for more than three days, and upon being cleared to fly again, my home airport was still off limits because of its proximity to the nation’s capital 20 miles to the southeast.

In the November 2001 issue of AOPA Pilot, I wrote about being stranded in Rolla, Missouri, with my family’s Beechcraft Baron while returning from an AOPA assignment in Wichita, Kansas (see “Where Were You? Grounded,” November 2001 AOPA Pilot). I was stranded for more than three days, and upon being cleared to fly again, my home airport was still off limits because of its proximity to the nation’s capital 20 miles to the southeast.

Being based at the Montgomery County Airpark in Gaithersburg, Maryland (GAI), felt like the punching bag of government officials rushing to impose ill-conceived restrictions in the days following 9/11. Changes in procedures to get in and out of the airport were common and led to the establishment of a (permanent) temporary flight restricted area that varied in size and strictness seemingly at the whim of the U.S. Secret Service or TSA. Many pilots and aircraft owners moved their airplanes to airports outside of restricted airspace, drastically cut back on flying, or simply quit. Traffic at the airport decreased dramatically and to this day is not as busy as it was in the 1990s.

Following the attacks, we could no longer just take off VFR and fly. The TFR, which later graduated to an air defense identification zone (ADIZ), required flight plans to be filed and a discrete transponder code entered. Taking off with a 1200 code led to an automatic violation for GA pilots within the ADIZ. Ironically, when this happened in the airliner I flew out of nearby Washington Dulles International Airport (also within the ADIZ), the controller casually said, “check your transponder.”

Following the attacks, we could no longer just take off VFR and fly. The TFR, which later graduated to an air defense identification zone (ADIZ), required flight plans to be filed and a discrete transponder code entered. Taking off with a 1200 code led to an automatic violation for GA pilots within the ADIZ. Ironically, when this happened in the airliner I flew out of nearby Washington Dulles International Airport (also within the ADIZ), the controller casually said, “check your transponder.”

ATC, now suddenly tasked with tagging and tracking every GA flight in the area, spun off new frequencies just for the purpose of checking the required boxes of having a transponder code and establishing radar and radio contact. This added another layer of communication complexity in some of the most complex airspace in the country, taxing the attention of both pilots and controllers. Flight following and Class B clearances became hard to come by, reducing safety and convenience as GA traffic was (and still is) jammed in corridors outside of TFRs and Class B boundaries. There was even a fatal crash within the ADIZ after a Piper Malibu mistakenly took off without a code and in the hasty return to land, the pilot lost control of the airplane.

Intercepts were common and fighter jets or helicopters would often escort violators to land at GAI, scaring the nearby neighbors and with each occurrence putting a black eye on GA. The more pilots ran afoul of the ADIZ, the more our freedom to fly would be threatened. Edicts and mandates that flew in the face of common sense (and of our country’s founding on individual freedom) required us pilots to either police ourselves or be dogged by ominous government regulations.

The airpark was soon completely surrounded by a tall fence with security gates. No longer could neighbors wander out to the airport and watch airport operations with their kids without an imposing fence in the way. So much for the friendly local airport. Now it is intimidating. All these years later, the airspace itself remains intimidating, leading many pilots to avoid it. Deterrence mission complete?

In February 2009, the ADIZ became a special flight rules area and made permanent most of the procedures already in place. The SFRA extends 30 nautical miles from the DCA VOR and a more restrictive flight restricted zone extends 15 nm from DCA. Mandatory online training is required for any pilot flying VFR within 60 nm of the DCA VOR. Although it took many more years than hoped, the incidences of airspace violations and intercepts have drastically fallen to rare occurrences. The procedures needed to fly from my local airport, while still annoying, have become commonplace to be essentially automatic now. To co-opt a hackneyed phrase, we’ve reached a new normal, sadly.

Peter A. Bedell is a captain at a major airline and is co-owner of a Cessna 172 and Beechcraft Baron.

The new normal

Reflections

The new normal

Security theater in a changed world

By Brian Schiff

It might seem strange that flying my jetliner on a severely clear day should remind me of the most tragic day in the history of aviation, but it does. That is what it was like on September 11, 2001, when a stern voice from ATC ordered my flight and all others to land at the nearest suitable airport (see “Where Were You? Message from Home,” November 2001 AOPA Pilot). This day made us recognize that airliners were no longer just instruments of commerce; they could also be used as weapons of war, fuel-laden missiles to be directed at vulnerable civilian targets.

It might seem strange that flying my jetliner on a severely clear day should remind me of the most tragic day in the history of aviation, but it does. That is what it was like on September 11, 2001, when a stern voice from ATC ordered my flight and all others to land at the nearest suitable airport (see “Where Were You? Message from Home,” November 2001 AOPA Pilot). This day made us recognize that airliners were no longer just instruments of commerce; they could also be used as weapons of war, fuel-laden missiles to be directed at vulnerable civilian targets.

It seems that whenever the airline industry survives one challenge, another comes along. No event, however, created as much long-term turmoil and chaos as did the events of 9/11 (although COVID-19 came close).

Crewmembers going through security are treated as part of the problem instead of the solution. After all, some 9/11 hijackers had previously posed as airline crewmembers. This has led to varying degrees of inconvenience. And hilarity, too. During one particularly rigorous search while in uniform, a TSA screener explained, “This is to ensure that you cannot take control of the flight!” I tried explaining to him that it was my job to take control, and that bad things would happen if I didn’t. When he was about to confiscate my nail clippers, I said, “You do know that we have a fire axe in the cockpit, right?” He seemed oblivious.

Crewmembers going through security are treated as part of the problem instead of the solution. After all, some 9/11 hijackers had previously posed as airline crewmembers. This has led to varying degrees of inconvenience. And hilarity, too. During one particularly rigorous search while in uniform, a TSA screener explained, “This is to ensure that you cannot take control of the flight!” I tried explaining to him that it was my job to take control, and that bad things would happen if I didn’t. When he was about to confiscate my nail clippers, I said, “You do know that we have a fire axe in the cockpit, right?” He seemed oblivious.

We understandably are no longer allowed to visit the cabin and mingle with passengers during flight. We also are protected from passengers coming forward by having been trained and licensed to carry handguns. A bulletproof cockpit door further protects us from hijackers. An inconvenient consequence of this is having to get permission from a flight attendant to visit the lavatory. He or she then blocks access to the front of the airplane by positioning a galley cart in the aisle. I have heard that the incidence of kidney stones among pilots is on the rise.

Brian Schiff is a captain for a major airline and CFI. He was flying an MD–80 on the morning of September 11, 2001.

Triumph out of tragedy

Triumph out of tragedy

United Airlines Flight 93 lives on in LeRoy W. Homer Jr. flight scholarships

By David Tulis

Tuesday morning, September 11, 2001, defined a generation after terrorists hijacked four commercial airliners and used them as weapons of war. Three crashed into symbols of America—the twin towers in New York City and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C.—and passengers on United Airlines Flight 93 saved countless others when they battled to veer the flight from the target of the hijackers who had seized control from Capt. Jason Dahl and First Officer LeRoy Homer Jr.

Tuesday morning, September 11, 2001, defined a generation after terrorists hijacked four commercial airliners and used them as weapons of war. Three crashed into symbols of America—the twin towers in New York City and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C.—and passengers on United Airlines Flight 93 saved countless others when they battled to veer the flight from the target of the hijackers who had seized control from Capt. Jason Dahl and First Officer LeRoy Homer Jr.

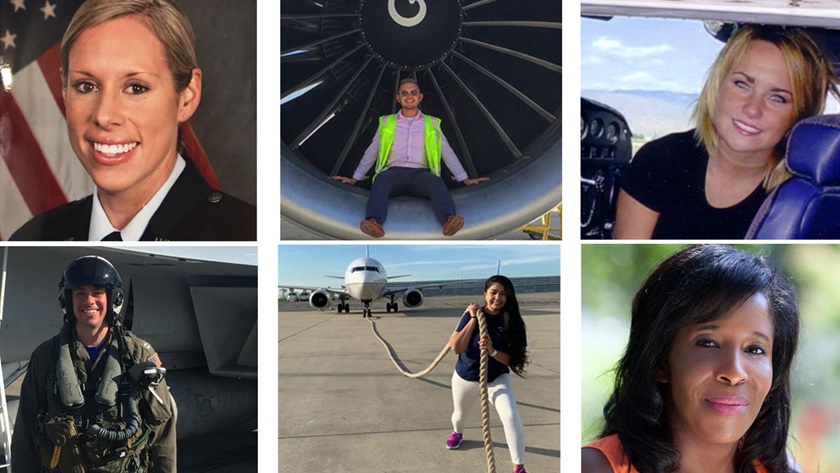

The LeRoy W. Homer Jr. Scholarship Foundation has turned tragedy into promise. The first officer’s widow, Melodie, pledged to keep her husband’s memory alive by fully funding primary flight training scholarships for those demonstrating a strong desire to pursue aviation, a balanced background, and a financial need.

Melodie Homer took her husband’s memory and decided to do something amazing with it.Melodie Homer said her husband would be “amazed” at the 25 young people who have already become pilots while keeping the pilot’s memory alive. She explained that flight training can vary widely depending on location, so the scholarships fund the entire expense—from the first day of ground school to the private pilot checkride—no matter the cost.

“We really wanted to look at this young adult population and sort of replicate what LeRoy did by having them follow in his footsteps,” and opening the doors to a variety of potential aviation careers.

She said the Homer flight scholarships recipients have a 100 percent completion rate and span military, commercial, and general aviation pilots. “We have four military pilots—two in the Air Force, two in the Navy—and two recipients who are currently at the Air Force Academy. We have people in the cockpit, we have people working in the airlines, we have people in cyber security, and we have people working at Boeing. We have cargo pilots, general aviators, and flight instructors.”

She said the Homer flight scholarships recipients have a 100 percent completion rate and span military, commercial, and general aviation pilots. “We have four military pilots—two in the Air Force, two in the Navy—and two recipients who are currently at the Air Force Academy. We have people in the cockpit, we have people working in the airlines, we have people in cyber security, and we have people working at Boeing. We have cargo pilots, general aviators, and flight instructors.”

Homer believes her husband’s “big plan was exactly what he did.” A U.S. Air Force Academy graduate, he flew for his country in “the exact plane that he wanted—the [Lockheed] C–131 Starlifter, and then he flew for the number-one airline, United. He really enjoyed what he did. He loved to travel, he loved to take pictures, and he loved taking advantage of being in other countries.” He discovered new places, went to museums, “and always came home with stories.”

She reconciles her personal loss with the solace that “United 93 was the flight that fought back. I often wonder if LeRoy was not on that flight, would it have made it to the U.S. Capitol that day?” Perhaps her husband’s position on the flight deck “was LeRoy’s purpose in life. I don’t like it, I don’t have to like it—but I understand that in his life, he had already taken an oath to protect and serve his country. That day was just an extension of it.”

Nineteen of the 27 recipients will attend an “Honoring the Past, Inspiring the Future” ceremony in Philadelphia August 28 to commemorate the twentieth anniversary of 9/11. Here are some of their stories.

Spirit airlines First Officer Sarah Cooke (2003 recipient) was 18 and fresh out of high school when her life trajectory changed forever. Cooke grew up “in the middle of nowhere Idaho” and didn’t have the financial resources to pursue an aviation career before she was awarded one of the first three LeRoy Homer Jr. Scholarship flight training scholarships.

She earned a private pilot certificate that summer and praised the award as the “single greatest gift that I’ve ever been given. That flight scholarship opened so many doors for me. It truly changed the direction of my life,” Cooke reflected. “I simply could not have afforded it. I grew up incredibly poor.”

Cooke also won the first-ever Captain Jason Dahl Scholarship, which funded an instrument rating and led to a United Express position. However, she was furloughed a short time later during the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009. “I did everything right, but there I was, 23 years old and unemployed, so I joined the Air Force.” She attended Officer Training School and is a distinguished U.S. Air Force graduate.

Cooke also won the first-ever Captain Jason Dahl Scholarship, which funded an instrument rating and led to a United Express position. However, she was furloughed a short time later during the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009. “I did everything right, but there I was, 23 years old and unemployed, so I joined the Air Force.” She attended Officer Training School and is a distinguished U.S. Air Force graduate.

She commanded a Boeing RC–135 reconnaissance aircraft “in international waters over countries you probably wouldn’t want to be near.” She considers military service one of her “proudest achievements.”

If Cooke met LeRoy Homer today, she said, “Oh, man, my eyes are going to water. I would tell him, ‘thank you’ for his legacy, and for his contributions to my life. I’m very fortunate. It’s just a really, really wonderful group of people.”

U.S. Navy Lt. Cmdr. Richard Valenta (2003), a Lockheed Martin F–35C Lightning II pilot based at Maryland’s Naval Air Station Patuxent River, was an inaugural scholarship recipient who knew at an early age that he wanted to become a military pilot. However, his parents “didn’t have the most money in the world and even in 2003 it was quite an expense to get a pilot license.”

One day he typed aviation scholarships on his computer “and the Homer Foundation popped up. Applications were due in like five days, and I said, ‘Oh, my gosh, I’ve got to get this done.’”

“It was such a life-changing day” when the 16-year-old was awarded an all-expenses-paid flight scholarship. He spent “every day at the airport that summer studying aviation and flying in a Cessna 152 with a single VOR, a single ADF, and a single radio, with a DG that precessed quite a bit.”

Earning a private pilot certificate at age 17 was “one of the most defining moments of my life,” Valenta said. Aviation classes at Purdue University, a Navy ROTC scholarship, and military flight training followed.

“I cannot stress to Melodie…and to everyone in the foundation how much of a positive impact that scholarship had on my life. I hope I can pay it back and give someone else the opportunity they gave me.”

U.S. Air Force Maj.Courtney Vidt (2006), an instructor pilot and weapons officer, praised the LeRoy Homer Scholarship Foundation for her aviation accomplishments. “The credit really belongs to Mel Homer. She took his memory and decided to do something amazing with it.”

The first recipient to graduate from the U.S. Air Force Academy, Vidt said even her passion for flying gliders mirrored Homer’s.

“It was really an honor to follow in his footsteps in general,” she said. Flying some of the same aircraft “at the same airfields, and walking down the same halls as LeRoy Homer, was a very humbling experience. Knowing that I’m pretty much following the footsteps that he laid out was surreal.” During her freshman year at the Academy, Vidt paid tribute to Homer at the reflecting wall where fallen graduates’ names are carved into stone.

Vishra Patel (2011) discovered aviation through EAA Young Eagles flights and attended ground school lessons as a 16-year-old. However, she was stumped about funding flight training lessons or pursuing a potential aviation career when so few airline pilots were female. “I’d never seen a female pilot, myself, so it kind of seemed to be an impossible dream until I found the LeRoy Homer Foundation.”

Patel was “over the moon” when she was awarded a full-ride flight training scholarship at age 17 and was floored when a mentor “sent me the Air Force wings she earned during her military training.” She said she still “gets chills” talking about it.

Patel earned a private pilot certificate in 69 days. “The day I got my license was the day I started my college career as well,” she said. She pursued aeronautical science at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, “which [is] a fancy way to say, ‘I’m majoring in becoming a pilot.’ It was an amazing experience.”

Patel earned a private pilot certificate in 69 days. “The day I got my license was the day I started my college career as well,” she said. She pursued aeronautical science at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, “which [is] a fancy way to say, ‘I’m majoring in becoming a pilot.’ It was an amazing experience.”

Patel changed her college trajectory from flying to pursuing aviation business with an eye on emerging airline security positions. A master’s degree in cyber-security engineering led to an information technology internship at United Airlines. The internship eventually led to a full-time career with the airline. Patel said she “absolutely enjoyed combining my passion for aviation and my newfound passion for cyber-security. It’s been a journey for sure, but it’s definitely been rewarding for me.”

Brody Wilson (2015) said the events of 9/11 were a national “tragedy, but we’ve made something awesome out of the circumstances we were dealt with.”

He learned he was selected as a LeRoy Homer Jr. Scholarship winner on the same day he graduated high school and the funds allowed him to kickstart his aviation career. He went at it vigorously, taking flight lessons nearly every day that summer.

Wilson earned his private pilot certificate on his eighteenth birthday and enrolled in Southern Illinois University’s aviation management and flight program. While in college he competed on the Flying Salukis National Intercollegiate Flying Association team, earning a national third place finish.

He applauds the Homer Foundation for helping young people pursue their aviation visions. “It took away a huge headache. Just having the financial help was instrumental in starting my career.” He said he was overwhelmed with emotions because “people believed in me and helped me achieve my goal.” The relationship developed into something stronger. “The people at the foundation are basically one big family. We keep up with each other and with our careers.”

If he could meet LeRoy Homer today, “I’d thank him for the sacrifice of his life for our country. The work Melodie Homer has done is huge. It has tremendously impacted every single recipient’s life.”

The 23-year-old is based in St. Louis flying as second-in-command in a Beechcraft King Air 200 and performing aerial surveys.

A life-saving mission

A life-saving mission amid the chaos

‘The only nonmilitary plane over North America today’

By Julie Summers Walker

It is not an urban legend. A flight took off in the early morning hours of Wednesday, September 12, 2001, from San Diego bound for Miami with special permission granted by the FAA. The Learjet 36 carried snake antivenom for a man who had been bitten by a taipan snake, the deadliest in the world, on September 11, 2001. The flight was accompanied by two fighter jets and landed at Miami’s Kendall-Tamiami Airport (now Miami Executive) at 4:30 p.m. Wednesday. It was “the only nonmilitary plane over North America today,” said the director of the hospital where the victim was being treated.

It is not an urban legend. A flight took off in the early morning hours of Wednesday, September 12, 2001, from San Diego bound for Miami with special permission granted by the FAA. The Learjet 36 carried snake antivenom for a man who had been bitten by a taipan snake, the deadliest in the world, on September 11, 2001. The flight was accompanied by two fighter jets and landed at Miami’s Kendall-Tamiami Airport (now Miami Executive) at 4:30 p.m. Wednesday. It was “the only nonmilitary plane over North America today,” said the director of the hospital where the victim was being treated.

Lawrence Van Sertima was a 63-year-old veteran snake handler, well-known to Miami-Dade’s Venom 1 unit of Miami-Dade Fire and Rescue, according to Capt. Al Cruz. Cruz started the venom unit, stocking the largest collection of antivenom (also known as antivenin) in the country. But Cruz would use all the taipan antivenom he had to save Van Sertima. Van Sertima had been putting the snake back in its cage when he was bit. He was taken by helicopter to Baptist Main Hospital where the antivenom was administered. The attempt to save his life used the five vials Venom 1 had on hand. The only other places that stocked it were in New York and San Diego. Obviously, New York was out, but Cruz found the antivenom at the San Diego Zoo. Now he had to convince the FAA to let a flight bring it to Florida.

After more than six hours of discussion, Cruz said, permission was granted at 3 a.m. The Chrysler Aviation flight piloted by John Rapis left San Diego at 9 a.m., traveling across the country to arrive in Florida and save Van Sertima with an additional five vials. Van Sertima is still alive and lives in North Carolina. He no longer handles deadly snakes, but his wife reportedly keeps a couple of king snakes in cages in their bedroom.

Christopher Freeze contributed to this story.