Air Boss Wayne Boggs scowled at the weather, taking shelter from a passing shower under a tent of blue tarps. Boggs, one of a small and elite group of experienced air bosses who run multiple airshows each year, had to make a tough call as a passing shower moved in: Boggs interrupted a tight schedule and told F4U Corsair pilot Dave Folk to cut it short and land as a small, wet crowd looked on at the Great Tennessee Air Show May 13.

Hours before, the pilots had synchronized watches with Boggs, who led a detailed safety brief on Sunday morning, just as he does every day they fly. Boggs told the pilots that it was ultimately their call whether to brave the weather. Ceilings hovered around 1,200 feet—just 200 feet above the FAA-required minimum—with twice the required three-mile visibility at best.

Veteran performer (and an aviation legend) J.W. “Corkey” Fornof, at left, and his fellow pilots paid close attention to the Sunday morning safety brief at the Great Tennessee Air Show. Also pictured, from left, Rob Holland, Matt Chapman, and others.

“If your sequence passes in bad weather, you can button up that airplane,” Boggs said.

“No one, and I repeat, no one needs to push on this. That way, I’ll see all of you all’s smiling faces (next time).”

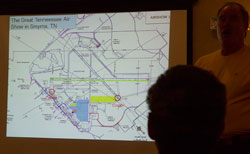

One key to airshow safety is the design of the performance area, which keeps the energy of high-performance aircraft directed away from the crowd.

One key to airshow safety is the design of the performance area, which keeps the energy of high-performance aircraft directed away from the crowd.

While precautions are extensive, a return to the ramp is never fully guaranteed: In 2011, after two years with no fatalities, five airshow performers died. They were among 16 killed in spectator events (airshows and air races) during the year—including a pilot and 10 spectators at the National Championship Air Races. The unusually deadly year has prompted fresh attention from the National Transportation Safety Board, which held a hearing Jan. 10, inviting Boggs, fellow professionals, and performers to brainstorm ideas to improve safety. Boggs had high praise for the NTSB’s approach.

“To me, the overall hearing was outstanding. They were very gracious individuals,” Boggs said. “It was not anything like a witch hunt.”

There was talk in January of requiring certification for air bosses, who have overall responsibility for organization, safety, and operations before and during the performances.

“I think there should be some type of certification,” Boggs said, noting that while a handful of elite air bosses travel a circuit of the largest shows, many smaller events are run by locals who may or may not have formal training in the myriad details that go into keeping everyone safe.

Air Boss Wayne Boggs kept close watch over the weather and cut one performance short as a passing shower doused the Great Tennessee Air Show.

Air Boss Wayne Boggs kept close watch over the weather and cut one performance short as a passing shower doused the Great Tennessee Air Show.

Boggs said airshow pilots, most of whom tour the country, have thousands of hours of flight time, and hold FAA waivers allowing low-level aerobatics, are an elite group of professionals who know their business. The lineup for the Great Tennessee Air Show was “the best of the best,” Boggs said, pilots he trusted to do the right thing at all times—including maintain utmost respect for the “aerobatic box,” airspace designed with care to keep the energy of high-performance aircraft directed away from the crowd.

In nearly 25 years of running airshows, Boggs has never had to use the command, “knock it off, knock it off, knock it off” that signals he believes a pilot is in peril. That, he said, is a reflection of the entire industry’s professionalism.

The command remains part of each and every safety brief, along with other details, such as the location of crash and rescue apparatus supplied by local firefighters.

Airshow performers and organizers work hard to keep danger away from the crowd, seen here on the first day of the show (May 12).

Airshow performers and organizers work hard to keep danger away from the crowd, seen here on the first day of the show (May 12).

“You come down to my show box like a bag of hammers, I guarantee you those fine folks will be right there to meet you,” Boggs said of the Smyrna, Tenn., fire and rescue crews.

Weather was the topic on most minds in the hotel conference room as Boggs turned the briefing over to a forecaster.

“Let’s stay focused, keep your game face on,” Boggs said. “Nobody needs to push.”

Airshows and air races are very different animals, Boggs said, with differing requirements to maintain safety. One NTSB recommendation to the air race organizers (and the FAA, which regulates and enforces all aviation activities) is to modify the race course design to limit the exposure of spectators to high-energy aircraft. Another is to conduct more stringent inspections and testing of the highly modified aircraft that race in the unlimited class—along with the pilots.

At airshows, each pilot, and each aircraft, must also pass a thorough FAA inspection before each performance. Veteran airshow pilot J.W. “Corkey” Fornof described it as “a ramp check on steroids,” one with which he is happy to comply. Fornof and other pilots credited Boggs as another key to safely executing maneuvers that include high-speed, low level passes and high-energy turns, citing a mutual trust built over the course of years.

Rain showers on May 13 drove performance aircraft from the flight line to the hangar. Rob Holland’s MX2 is in the foreground.

Rain showers on May 13 drove performance aircraft from the flight line to the hangar. Rob Holland’s MX2 is in the foreground.

Minute by minute, the sequences passed. Airshow staff, pilots, and crews wrangled aircraft (including the relatively giant Corsair) in and out of a hangar as rain came down in fits and starts. Radios buzzed, and Boggs kept in touch with forecasters, show staff, and tower controllers by cellphone as well, pulling in the latest available images and data.

Despite the passing showers, which cut one performance short and curtailed a couple of others, spectators were treated to hours of aviation entertainment by the time Boggs turned the airshow box over to the U.S. Navy Blue Angels at 3 p.m. Like all military teams, they maintain their own airshow direction and make their own decisions. On May 13, the F/A-18 pilots performed a “flat” show, orchestrating maneuvers in perfect synchronization under lowering clouds.

The fire trucks and crews stood by, left only to watch.