Understanding Part 23 Rewrite

On March 9, 2016, the FAA published a notice of proposed rulemaking entitled “Revision of Airworthiness Standards for Normal, Utility, Acrobatic, and Commuter Category Airplanes” (Part 23 NPRM). The purpose of the proposed rulemaking is to amend the airworthiness standards for normal, utility, acrobatic, and commuter category airplanes certified under 14 CFR Part 23 by removing the current prescriptive design requirements and replacing them with performance-based airworthiness standards.

General Information

1. When was the Part 23 NPRM published and when will it go into effect?

The Part 23 NPRM was posted to the FAA’s website March 9, 2016, and was published in the Federal Register March 14, 2016. The 60-day window for submitting comments ended on May 13, 2016. The proposed rulemaking does not become effective until the FAA publishes a separate final rule.

2. Where can AOPA members review the Part 23 NPRM?

AOPA members can review the Part 23 NPRM here in the Federal Register.

3. How did the Part 23 NPRM come about?

- 2009 – A joint FAA and industry team produced the Part 23 Certification Process Study (CPS), which developed key recommendations to reorganize Part 23 based on performance and complexity rather than weight and propulsion divisions.

- 2010 – The FAA conducted a Part 23 Regulatory Review, which confirmed strong public and industry support for the CPS recommendations to revise Part 23.

- 2011 – The Part 23 Reorganization Aviation Rulemaking Committee (ARC) published a report echoing the sentiments of the CPS.

- January 7, 2013 – Congress passed the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012, which required the FAA to assess the aircraft certification and approval process.

- September 24, 2013 – FAA rulemaking efforts began on the Part 23 NPRM.

- November 27, 2013 – Congress passed the Small Airplane Revitalization Act of 2013, which required the FAA to issue a final rule revising the certification requirements for small airplanes.

The Part 23 NPRM addresses the requirements set forth in the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 and the Small Airplane Revitalization Act of 2013.

Certifying Part 23 Airplanes

4. How does a type certificate applicant comply with 14 CFR Part 23 certification standards under the existing regulatory framework?

For a manufacturer to obtain a type certificate for a typical general aviation airplane under existing regulations, the applicant’s airplane design must comply with the standards set forth in Part 23. The applicant has two “means” of complying:

- First, the applicant may demonstrate compliance with the specific prescriptive provisions set forth in Part 23 for each aspect of the design (e.g., structure, powerplant, landing gear).

- Second, the applicant may demonstrate that its design should be exempt from the particular regulatory standard or that it provides an equivalent level of safety for other reasons.

5. How does a type certificate applicant demonstrate compliance with 14 CFR Part 23 certification standards under the existing regulatory framework?

The type certificate applicant must show the FAA how it satisfies the applicable airworthiness standards in Part 23. The applicant commonly submits the type design, test reports, and computations/analysis necessary to demonstrate compliance. The applicant then approaches, negotiates, and works with the FAA regarding what constitutes adequate demonstration.

6. How does the Part 23 NPRM affect the current process of demonstrating compliance with 14 CFR Part 23 certification standards?

The Part 23 NPRM retains both of the options listed in Question 5 for demonstrating compliance with Part 23 certification standards. However, the proposal adds a third option: complying with “performance-based standards,” which the FAA has promulgated in the proposed Part 23.

7. What is a performance-based standard?

A performance-based standard establishes a level of performance that must be achieved through the airplane’s design, rather than dictating how a manufacturer should arrive at a particular level of performance. For instance, proposed § 23.750(a) states: “The airplane cabin exit design must provide for evacuation of the airplane within 90 seconds in conditions likely to occur following an emergency landing.” The standard states the expected performance of any proposed design for an emergency cabin exit—it does not state how the design should be accomplished (e.g., cabin lighting, marking) to achieve that performance.

8. How does a type certificate applicant demonstrate compliance with a performance-based standard?

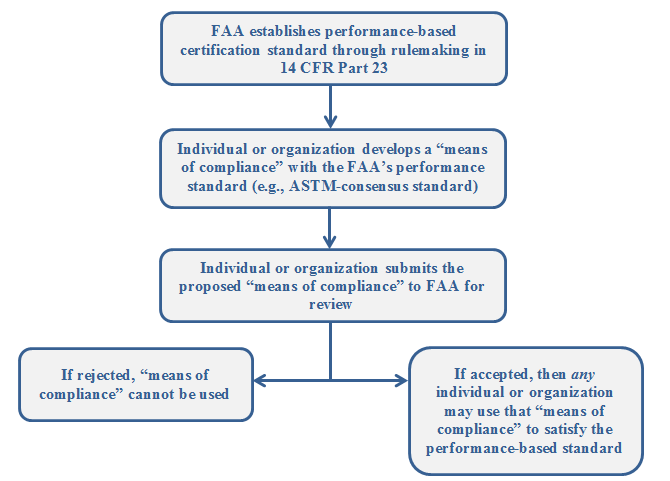

This question highlights one of the FAA’s fundamental shifts in certification philosophy. The following flowchart illustrates the FAA’s proposed method for demonstrating compliance with the new 14 CFR Part 23 performance-based standards in the Part 23 NPRM.

Consider the following example to put this process in context: ASTM International is an organization with committees that are primarily composed of government representatives (e.g., the FAA) and industry groups. The various committees develop technical consensus standards for a range of different industries. Suppose ASTM publishes a consensus standard for the development of an electric propulsion system using batteries and fuel cells as fuel. This ASTM-consensus standard would be a proposed “means of compliance” to satisfy the new Part 23 fuel system performance-based standard. The proposed ASTM-consensus standard would then be sent to the FAA for acceptance. If accepted, any individual or company can then satisfy the new performance-based regulation in Part 23 by complying with that FAA-accepted ASTM standard.

9. Why are performance-based standards being introduced? How does this make the system better?

The existing Part 23 certification standards are very detailed—focusing more on specific design features rather than the system as a whole—and are based upon designs from the 1950s and 1960s. Because of the existing rigid framework, any manufacturer seeking design approval for modern technology often must provide additional documentation and data, which results in the FAA issuing special conditions, exemptions, or an equivalent level of safety (ELOS) finding in order to demonstrate that the manufacturer has complied with the certification standard.

- Example 1: Using the electric propulsion system example presented in Question 8; existing fuel system standards do not contemplate an electric propulsion system using batteries and fuel cells as fuel—the applicant would instead have to apply for an exemption or special condition. Under the framework proposed, an applicant would only have to demonstrate compliance with the FAA-accepted ASTM standard to satisfy the requirements of Part 23. The applicant would not have to spend the time and resources to apply for an exemption or special condition.

- Example 2: Current Part 23 crashworthiness and occupant safety requirements are based on seat and restraint technology from the 1980s. Existing certification standards require that an applicant demonstrate crashworthiness by a sled test. New standards in the Part 23 NPRM do not require a sled test, but allow for different methods accounting for many other factors. So instead of forcing an applicant into antiquated testing, the performance-based regulations provide flexibility on how to meet the broader crashworthiness objective. This flexibility can lead to new safety-testing methodologies and advanced safety technology.

As the illustrations demonstrate, there are many anticipated benefits from the proposed rulemaking, including:

- Encouraging the development and installation of innovative and safer product designs

- Streamlining the certification process to reduce the time and costs of certification for manufacturers/industry and the FAA

- Maintaining the same level of safety that currently exists under the current Part 23 certification standards

10. Are the performance-based standards applicable to all aircraft?

No. The new process of using performance-based standards is limited to new airplanes certified under Part 23, which would include airplanes with a maximum passenger-seating configuration of 19 or less, and a maximum certificated takeoff weight of 19,000 pounds or less.

11. How do the proposed changes compare with international standards?

The FAA has worked with foreign civil aviation authorities (CAAs) to ensure international harmonization of airworthiness standards and to address any unnecessary certification differences that may be burdensome on the GA industry. Foreign CAAs from Europe, Canada, Brazil, China, and New Zealand are in the process of producing similar regulations and rules as set forth in the Part 23 NPRM. The European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) published an advanced notice of proposed rulemaking in March 2015, which was also based upon recommendations from the Part 23 Reorganization ARC.

Part 23 Certification Classifications

12. What types of airplanes are certified under the existing 14 CFR Part 23 certification standards?

Under current 14 CFR Part 23, airplanes are certified in one or more of the following categories: normal, utility, acrobatic, and commuter. Classification primarily depends upon the types of maneuvers to be performed, number of seats, number of engines, and maximum certificated takeoff weight.

13. Will the FAA continue to certify airplanes in four categories (normal, utility, acrobatic, and commuter) under the proposed 14 CFR Part 23?

No. The FAA proposes to eliminate commuter, utility, and acrobatic airplane categories from Part 23. All newly certificated airplanes under Part 23 would be certified in the normal category. Airplanes already certified in the commuter, utility, acrobatic, or normal categories will continue to fall in those categories. Under the proposed rulemaking, all normal category airplanes would have a maximum seating capacity of 19 passengers or less, and a maximum takeoff weight of 19,000 pounds or less.

14. Will all normal category airplanes be certified to the same standards under the proposed 14 CFR Part 23?

No. Certification standards for a normal category airplane within the proposed Part 23 will depend upon the airplane design’s (1) risk level (e.g., maximum number of passengers), and (2) performance level (e.g., speed). Airplane designs will be assigned a “certification” level and a “performance” level in accordance with the following chart:

| Airplane Certification Levels | Airplane Performance Levels | ||

| Level 1 | Maximum seating configuration of 0 to 1 passengers | Low Speed | Airplanes with a VC or VMO ≤ 250 KCAS (and MMO ≤ 0.6) |

| Level 2 | Maximum seating configuration of 2 to 6 passengers | ||

| Level 3 | Maximum seating configuration of 7 to 9 passengers | High Speed | Airplanes with a VC or VMO > 250 KCAS (and MMO > 0.6) |

| Level 4 | Maximum seating configuration of 10 to 19 passengers | ||

*VC = design cruise speed; VMO = maximum operating limit speed; MMO = maximum operating Mach number

The FAA has proposed a “sub-level” within Level 1 called the “simple airplane.” A “simple airplane” is defined as a Level 1 airplane that has a VC or VMO ≤ 250 KCAS (and MMO ≤ 0.6) and a VSO ≤ 45 KCAS, and is approved only for VFR operations.

Certification standards for various aspects of an airplane’s design would vary depending upon its certification and performance levels. As shown in the following chart, more stringent standards would apply to Level 4 high speed airplanes, which are higher risk and higher performance airplanes, than a Level 1 low speed airplane. This is consistent with the FAA’s philosophy and emphasis on restructuring regulatory requirements based on perceived risk.

| Certification Levels | ||||

| Performance Levels |

Level 1 Low Speed |

Level 2 Low Speed |

Level 3 Low Speed |

Level 4 Low Speed |

|

Level 1 High Speed |

Level 2 High Speed |

Level 3 High Speed |

Level 4 High Speed |

|

Part 23 Certification Standards

15. What existing 14 CFR Part 23 certification standards have been changed by the Part 23 NPRM?

The FAA has rewritten the entire 14 CFR Part 23, changing the existing prescriptive certification standards to performance-based standards for a number of aspects of an airplane’s design. Summarizing each rewrite would be too burdensome in this context. The Part 23 NPRM includes a cross-reference table showing where existing Part 23 sections and requirements may be found, if at all, in the proposed Part 23. Please refer to this table for a comparison of how specific existing standards have been modified or removed.

Despite the significant rewrite and change in certification approach, the FAA emphasizes that the performance-based standards in the proposed Part 23 are designed to maintain the level of safety currently provided through the existing Part 23 requirements.

16. Has the FAA added any new standards for airplanes certified under the proposed 14 CFR Part 23?

The FAA has added several certification standards under the proposed Part 23 that should be noted:

- First, the FAA proposes to increase the level of safety for an airplane’s stall characteristics and stall warnings by (1) ensuring airplane designs are more resistant to inadvertent stalling/departing from controlled flight, (2) requiring more effective stall warnings, and (3) improving pilot awareness of stall margins.

- Second, the FAA proposes to require the stall speed (VS1 or VS0) to be greater than the minimum control speed (VMC) for each configuration within the operating envelope of Level 1 and Level 2 multi-engine airplanes. Under the current framework, VMC is typically greater than the stall speed. This change was based on the FAA and ARC’s finding that when a pilot lost one engine, he or she would maintain a climb or altitude, which reduced the speed of the aircraft, often below VMC. This resulted in a loss of directional control. By ensuring VMC is below stall speed, the FAA believes that pilots will not continue to climb or maintain their altitude. Instead, the pilot will return to his or her stall training and perform a controlled descent, which would prevent any loss of control by going below VMC.

- Third, the FAA proposes new standards to address severe icing conditions, which will include supercooled large drops (SLD), mixed phase, and ice crystals. Under the proposal, manufacturers would have two options:

- (1) To certify an airplane for flight in SLD, the manufacturer must demonstrate safe operations in SLD conditions.

- (2) To certify an airplane with a prohibition on flying in SLD conditions, the FAA requires a means for detecting SLD conditions, and the manufacturer must demonstrate that the airplane can exit such conditions.

17. Why did the FAA add new Part 23 certification standards for stall characteristics and stall warnings?

The FAA’s new Part 23 certification standards for stall characteristics and stall warnings are meant to reduce the number of loss-of-control accidents, or cases where a pilot departs from controlled flight. Loss-of-control accidents have proven to be the most common cause of small airplane fatal accidents, and the FAA is taking the opportunity during the rewrite to address this problem.

18. Why did the FAA add new Part 23 certification standards for flight in severe icing conditions?

The FAA’s new Part 23 certification standards for flight in severe icing conditions arose from an accident in Roselawn, Indiana, in 1994 involving an Avions de Transport Regional ATR 72 series airplane in SLD conditions. Consistent with NTSB recommendations and a study from the FAA’s Aviation Rulemaking Advisory Committee, the FAA amended 14 CFR Part 25 and Part 33 icing requirements to address the effects from SLD, mixed phase, and ice crystal icing conditions. No changes were made to Part 23. The proposed rulemaking derived from a recommendation from the Part 23 Icing ARC, which was chartered by the FAA in 2010.

AOPA Role and Position

19. What is AOPA’s involvement?

AOPA has been actively engaged in identifying ways to streamline the certification process, serving on the FAA’s Certification Process Study; the Part 23 Reorganization ARC, which developed the recommendations for reforms; and the ASTM F44 Committee, which is developing industry consensus standards for the Part 23 rulemaking effort.

20. What is AOPA’s position on revising 14 CFR Part 23?

AOPA has long supported and advocated for revising 14 CFR Part 23 to reduce the costs and resources needed for certifying and introducing new GA aircraft and advanced technologies into the marketplace without comprising safety. AOPA has reviewed the draft proposal thoroughly and, along with other industry organizations, filed comments ahead of the deadline.