Make no mistake, the year 2009 will go down as one of general aviation’s worst years in decades. From the time the recession first raised its head in the fall of 2008, airframe manufacturers recorded ever-steepening declines in demand, orders, billings, and deliveries of new aircraft. This drop in business has been nothing short of breathtaking. According to the General Aviation Manufacturers Association (GAMA), which represents 67 fixed-wing airplane manufacturers around the world, 2009 year-to-date deliveries (as of this writing) totaled 1,587 aircraft. In 2008, deliveries totaled 2,982 aircraft, making for a one-year drop of 46.8 percent. In 2007—comparative boom times—total delivery numbers were even higher than 2008’s, at a whopping 4,272 airplanes.

Turbine trends

The 2009 slump didn’t affect all airplane types equally. Large-cabin business jets and turboprops showed more strength than piston singles, for example. Leaders included Bombardier’s Global 5000 and Global Express XRS (42 versus 51 in 2008); Dassault Falcon Jet’s newly-designed Falcon 7X (21 in 2008, 18 year to date in 2009); and Gulfstream’s G350/450/500/550 series, with 56 sales year to date in 2009, compared to 88 airplanes in 2008. Much of this success can be attributed to strong international demand and the weakness of the U.S. dollar.  In other big-iron news, a few companies demonstrated faith in the future by hanging in there with plans made years ago. Bombardier, for example, announced continued progress on its new, all-composite Learjet 85. Gulfstream rolled out its new, top-of-the-line G650, as well as its new, mid-sized G250. Brazil’s Embraer certified its new Phenom 300, continued development work on its Legacy 450 and 500 mid-sized jets, and announced a new project—the Legacy 650 large-cabin business jet. Piper continued work on its PiperJet; Honda announced a delay in its HondaJet program (but continued work); and Daher-Socata and Pilatus held their ground with their TBM 850 (23 airplanes year to date) and PC-12NG (64 airplanes year to date), respectively.

In other big-iron news, a few companies demonstrated faith in the future by hanging in there with plans made years ago. Bombardier, for example, announced continued progress on its new, all-composite Learjet 85. Gulfstream rolled out its new, top-of-the-line G650, as well as its new, mid-sized G250. Brazil’s Embraer certified its new Phenom 300, continued development work on its Legacy 450 and 500 mid-sized jets, and announced a new project—the Legacy 650 large-cabin business jet. Piper continued work on its PiperJet; Honda announced a delay in its HondaJet program (but continued work); and Daher-Socata and Pilatus held their ground with their TBM 850 (23 airplanes year to date) and PC-12NG (64 airplanes year to date), respectively.

But for every bright spot, there were setbacks. Cessna began 2009 by laying off more than 4,600 of its 16,000 workers, and even more layoffs followed in the ensuing months. Plans for Cessna’s new big-cabin Columbus twinjet were canceled. Hawker Beechcraft Corporation (HBC) had more than 3,000 layoffs, closed its Salina, Kan., plant, and put plans for its Premier II business jet on hold. Embraer laid off 4,200 employees.

The very light jet (VLJ) market was a mixed bag. The proliferation of VLJs that peaked in 2008 continued a shakeout in 2009 when Eclipse Aviation Corporation went bankrupt, and then was sold to a group of Eclipse 500 owners. Similarly, Epic Aircraft—which planned to build its Epic Elite twinjet and Epic Dynasty single-engine turboprop—went out of business. On the other hand, Embraer saw an upsurge in its new Phenom 100 light jet, with 48 deliveries in 2009. And despite Cessna’s otherwise troubling sales performance, that company’s Mustang light jet sold to the tune of 94 airplanes by year to date 2009; its Caravan single-engine turboprop also fared well, with year-to-date deliveries of 68 airplanes.

The very light jet (VLJ) market was a mixed bag. The proliferation of VLJs that peaked in 2008 continued a shakeout in 2009 when Eclipse Aviation Corporation went bankrupt, and then was sold to a group of Eclipse 500 owners. Similarly, Epic Aircraft—which planned to build its Epic Elite twinjet and Epic Dynasty single-engine turboprop—went out of business. On the other hand, Embraer saw an upsurge in its new Phenom 100 light jet, with 48 deliveries in 2009. And despite Cessna’s otherwise troubling sales performance, that company’s Mustang light jet sold to the tune of 94 airplanes by year to date 2009; its Caravan single-engine turboprop also fared well, with year-to-date deliveries of 68 airplanes.

Speaking of turboprops, this category showed continued strength, relatively speaking in this down market. Where business jet shipments fell 37.8 percent from 2008 to 2009, turboprop shipments declined by just 15.8 percent—to 293 airplanes from 348 in 2008. In these stressed-out economic times, turboprops apparently make more sense for two principal reasons: They aren’t as ostentious as jets, and they are more economical to operate over typical stage lengths—300 to 500 nautical miles. In this category, HBC’s King Airs came up comparatively strong—as always—with deliveries of 30 C90GTis, 22 B200s, and 22 350s.

Piston problems, and opportunities

The market for piston-powered airplanes was the most depressed in 2009, with only 679 airplanes delivered year-to-date. In 2008, total piston deliveries amounted to 1,646 units. The major players in this segment—Cessna, Cirrus, Diamond, HBC, and Piper--all saw dramatic sales downturns and layoffs. For example, Cirrus, which was going strong with 549 sales in 2008 saw business fall to 189 airplanes this year. Consequently, that company laid off some 550 employees.

Diamond Aircraft deserves credit in 2009 for staring down the recession with special resolve. After Thielert Aircraft Engines’ bankruptcy, the company was deprived of its traditional source of turbodiesel piston engines for its DA42 Twinstar piston twins. So the decision was made to commission its own engines. This year, Diamond’s newly formed Austro engine division certified the first of the Austro 3000 series of turbodiesels.

Diamond Aircraft deserves credit in 2009 for staring down the recession with special resolve. After Thielert Aircraft Engines’ bankruptcy, the company was deprived of its traditional source of turbodiesel piston engines for its DA42 Twinstar piston twins. So the decision was made to commission its own engines. This year, Diamond’s newly formed Austro engine division certified the first of the Austro 3000 series of turbodiesels.

Diamond then went on to certify its DA42NG with the new engines, as well as develop a retrofit kit for existing Thielert-powered DA42 Twinstars. At the same time, Diamond certified the DA42 with twin Lycoming IO-360, 180-hp engines, and the first dozen of these airplanes were delivered in the fall of 2009. As if that weren’t enough, Diamond pressed ahead with its D-JET single-engine VLJ—which should be certified in 2010.

In other positive news, Cessna completed certification of its newest entry-level piston single, the Cessna 162 SkyCatcher. After two spin-related crashes during flight testing, the airplane’s vertical stabilizer and dorsal fin were modified, the airplane was signed off, and the first SkyCatcher was delivered this month. There are orders for more than 1,000 of the $111,500 airplanes, which are in the light sport aircraft (LSA) category.

In other positive news, Cessna completed certification of its newest entry-level piston single, the Cessna 162 SkyCatcher. After two spin-related crashes during flight testing, the airplane’s vertical stabilizer and dorsal fin were modified, the airplane was signed off, and the first SkyCatcher was delivered this month. There are orders for more than 1,000 of the $111,500 airplanes, which are in the light sport aircraft (LSA) category.

LSAs, by the way, continued to make inroads in markets around the world. In 2009, there were some 1,688 LSAs flying in the United States, with many of them serving as training aircraft. Cessna’s SkyCatcher not only secured its own market share in the LSA market, but had the larger impact of further validating the LSA concept. It says something when a player as big as Cessna invests in a new LSA.

Another new development was the emergence of the first electrically-powered lightplanes. Yuneec, a Chinese company, came out with a battery-powered electrical engine that some LSA manufacturers are using to develop prototype designs. Flight Design, of Woodstock, Conn., for example, flew its Yuneec-powered e-Spyder ultralight for the first time in 2009. While current-design batteries permit endurances of no more than two hours, longer-lived lithium-polymer batteries are in the works. Flight Design also developed a hybrid powerplant that adds a supplementary/backup electrical motor to its conventional Rotax engine. The move to electrical powerplants, like the emerging trends in solar-cell-powered aircraft, is in large part an effort to come to terms with environmental issues.

Another new development was the emergence of the first electrically-powered lightplanes. Yuneec, a Chinese company, came out with a battery-powered electrical engine that some LSA manufacturers are using to develop prototype designs. Flight Design, of Woodstock, Conn., for example, flew its Yuneec-powered e-Spyder ultralight for the first time in 2009. While current-design batteries permit endurances of no more than two hours, longer-lived lithium-polymer batteries are in the works. Flight Design also developed a hybrid powerplant that adds a supplementary/backup electrical motor to its conventional Rotax engine. The move to electrical powerplants, like the emerging trends in solar-cell-powered aircraft, is in large part an effort to come to terms with environmental issues.

Retrofits, and the used market

With economic pressures forcing owners to unload their aircraft, the inventory of used aircraft of all types saw an increase. Earlier in the year, this glut drove prices down and led to some incredible deals on high-end airplanes. Jets that sold for $5 million on the used market two years ago now go for $2 million—or less. But as the economy regains strength, inventories have been dropping, and values of used aircraft have been rising lately. Prices are firming, and in many cases, bidding up.

With economic pressures forcing owners to unload their aircraft, the inventory of used aircraft of all types saw an increase. Earlier in the year, this glut drove prices down and led to some incredible deals on high-end airplanes. Jets that sold for $5 million on the used market two years ago now go for $2 million—or less. But as the economy regains strength, inventories have been dropping, and values of used aircraft have been rising lately. Prices are firming, and in many cases, bidding up.

According to the Aircraft Bluebook Price Digest, the following are among the used airplanes that are currently gaining in value: Lear 31As, Cessna Mustangs, Piaggio P180s, Piper Cheyennes, Beechcraft King Air 300s and 350s, Piper Aerostars, and Cessna 421s. Among piston singles, the Cirrus SR20 leads the pack, although all piston singles are upward-bound, save for certain Mooneys.

The retrofit market took a hit in 2009, but its fortunes also may be turning around. For example, Blackhawk Modifications, Inc.—which had a record sales year in 2008—has spent 2009 certifying the Piper Cheyenne I and Cessna Caravan with more powerful PT6A engines. “We’re making new upgrades for when the tide shifts,” a spokesman said. In the same vein, Texas Turbines certified a modification to install a 900-shp Honeywell engine, also in the Cessna Caravan.

Avionics upsurge

While avionics manufacturers weren’t spared the market downturn, they have also been investing in new products, and in the panel-retrofit market. Leading the list is Garmin’s certification of its G1000 avionics suite in the King Airs C90B and B200, and Daher-Socata’s TBM 700. Garmin also rolled out its new G500 and G600—designed specifically for the retrofit market—as well as its new, touchscreen-activation G3000 avionics suite. The G3000 will be standard equipment in Piper’s upcoming PiperJet and Honda’s in-development HondaJet. Garmin also introduced a new handheld GPS receiver— the Aera—which also uses touchscreen technology for data entry, and which replaces its model 396 and 496 handhelds.

While avionics manufacturers weren’t spared the market downturn, they have also been investing in new products, and in the panel-retrofit market. Leading the list is Garmin’s certification of its G1000 avionics suite in the King Airs C90B and B200, and Daher-Socata’s TBM 700. Garmin also rolled out its new G500 and G600—designed specifically for the retrofit market—as well as its new, touchscreen-activation G3000 avionics suite. The G3000 will be standard equipment in Piper’s upcoming PiperJet and Honda’s in-development HondaJet. Garmin also introduced a new handheld GPS receiver— the Aera—which also uses touchscreen technology for data entry, and which replaces its model 396 and 496 handhelds.

Bendix/King by Honeywell also took the time to introduce new offerings. One, the KFD 840, is aimed at the piston retrofit market, and replaces the conventional “six-pack” of round gauges in thousands of aircraft with a single, large-screen primary flight display with vertical-tape instrument presentations and its own attitude and heading reference system. The latter eliminates the need for vacuum-driven instruments. Honeywell also brought out a new handheld electronic flight bag— the AV8OR Ace—that features electronic charts, terrain information, and many other features, plus the usual navigation datasets that you’d expect from any high-end portable GPS receiver.

The longer view

Are we seeing the light at the end of the tunnel? Evidence would seem to support this. As we’ve seen, several manufacturers are taking advantage of the downswing to prepare future products timed for introduction when business turns around. The economy has begun a modest rally in these past few months, and inspired confidence in the entire general aviation community.

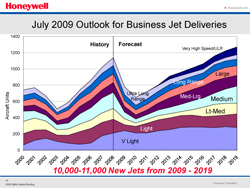

Honeywell Aerospace, which puts out a much-anticipated annual aviation business forecast, said in October that 2010 will be a bad year for airframe manufacturers, with deliveries of new airplanes at even lower levels than in 2009. But that will mark the bottom of the downturn. By 2011, Honeywell predicted that significant pent-up demand will improve the outlook for order intake and an upswing of new airplane deliveries. “There is every reason to believe that demand will begin to recover 12 to 18 months after a global economic recovery begins,” Honeywell stated.

Honeywell Aerospace, which puts out a much-anticipated annual aviation business forecast, said in October that 2010 will be a bad year for airframe manufacturers, with deliveries of new airplanes at even lower levels than in 2009. But that will mark the bottom of the downturn. By 2011, Honeywell predicted that significant pent-up demand will improve the outlook for order intake and an upswing of new airplane deliveries. “There is every reason to believe that demand will begin to recover 12 to 18 months after a global economic recovery begins,” Honeywell stated.

That recovery seems to have already begun. The signs are there, if you look for them. Attendance at this year’s EAA AirVenture rose to 578,000 aviation enthusiasts—12 percent more than 2008’s 540,000 attendees. If nothing else, this proves that the spirit is thriving. And when hopes are up, the market soon follows. We’ve seen it before, in spades, in the early 1980s. In 1979, nearly 18,000 new GA airplanes were delivered. By 1983 that number fell to some 400 airplanes—in large part because of manufacturer concerns about punitive product liability settlements. But GA turned around after the General Aviation Revitalization Act of 1994, which limited those settlements. We rallied then, and we’ll rally in the future.