Some in aviation blame general aviation for airport delays. So we asked former Inspector General of the U.S. Department of Transportation Ken Mead to take a close look at the delay data, and the results are in: Next time an airline spokesman points a finger at GA because of airport delays, remember the facts.

As the holiday season approaches, airline passengers brace for the delays and cancellations that too often accompany commercial air travel. The problem of airline delays has vexed analysts for years, and there has been little appreciable improvement, particularly when the U.S. economy is strong. The recent economic downturn has reduced airline flight volumes in response to reduced passenger demand. Nevertheless, just as the summer 2009 data was being compiled, passengers waited on the tarmac at New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport nearly six hours for a two-and-a-half hour flight to Minneapolis-St. Paul.

Airport capacity, airline scheduling, and the efficiency of airspace use all contribute to the delay profiles of the most congested airports, and learning more about the causes of delays can help us find solutions. In the same way, misidentifying the cause of delays can impede progress toward solutions and serve as a distraction from the real problems.

For years, the idea has persisted that sharing the runway, airspace, and air traffic control resources with smaller general aviation aircraft causes commercial aircraft to be late. In fact, GA’s contribution to these delays is negligible, and the myth that it is a major contributor to airline delays could lead to additional restrictions on GA flying and demands that GA pay significantly higher charges and user fees—without relieving delays at commercial airports.

Of all the busy commercial airports in the nation, the New York metropolitan area stands out for its particularly bad delay profile. The three major New York airports—JFK, LaGuardia, and Newark—have been major choke points for delays that cascade throughout the entire National Airspace System (NAS).

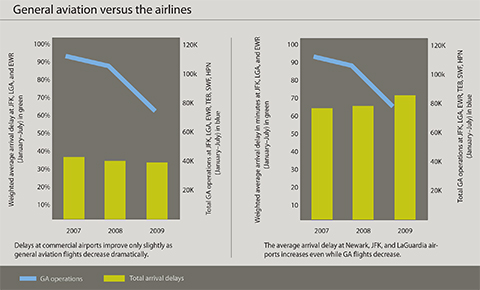

The past few years have seen a dramatic decrease in GA operations at the three major air carrier airports in the New York area, in addition to the nearby GA airports at Teterboro, New Jersey, and Newburgh and White Plains, New York. If GA contributed in any material way to airline delays, then one would expect a double-digit percentage decline in GA operations to provide air carrier passengers with significant relief from long waits in the terminal and on the tarmac. This has not happened.Instead, the percentage of delayed flights has improved only slightly; it’s comparable to delays in 2007, at the height of New York airspace congestion—and, for those whose flights are delayed, the wait can be even longer.The causes of airline delays are numerous and complicated, but one thing is clear: The airlines cannot simply point to GA as the cause of delayed flights.

In 2007, delays at the New York airports had reached a high, attracting national media attention and prompting scores of congressional inquiries into the causes of and possible solutions to the delays. Economic pressures and caps on operations at the airports hit both airlines and GA after that, but GA was hit much harder. GA operations declined 37 percent at the three major New York airports over the next two years; air carrier operations dropped 2 percent. Nationally, GA operations decreased 16 percent since 2007, and air carrier operations decreased 6 percent. (The number of operations has been calculated from data made public through the FAA Air Traffic Activity Data System—ATADS. Data include January through July of both years, using the latest data available for 2009.) However, those sharp declines in GA traffic at New York airports have not translated to significant reductions in delays.

With fewer aircraft operating at the airports, the percentage of delayed aircraft decreased only modestly, and at Newark delays are worse this year than last. And the length of delays actually got worse at the New York-area airports. In 2007, 37 percent of flights at the three major New York airports were delayed, and the average delay was 67 minutes.

In 2009, 32 percent of flights were delayed, and the average delay increased to 72 minutes. (Delay data are compiled from arrival information provided by the Bureau of Transportation Statistics. A flight is considered delayed if it arrives at the gate 15 minutes or more after the scheduled arrival time.)

It also is not accurate to offer up an explanation that GA pilots simply shifted operations away from JFK, LaGuardia, and Newark to other area airports that use the same ATC facilities as the larger airports. The nearby airports of Teterboro, Stewart, and Westchester County also experienced double-digit percentage declines in GA traffic: 24 percent from 2007 to 2009 for the period of January to July.

In total, the number of GA aircraft being routed to or from the six New York-area airports has dropped by 25 percent—a total of about 42,500 operations for the seven-month period, compared with a drop in air carrier operations of about 11,500. (Those airports currently handle more than three and one-half times the number of commercial operations as GA operations.) Yet the delay statistics for the New York airports remain persistently high—about one in every three flights.

In terms of steep GA traffic declines and the effect of those declines on air carrier delays, data from major airports around the country show trends similar to those in New York—GA traffic has an insignificant effect on air carrier delays.

GA operations at Atlanta dropped 37 percent in two years, but the percentage of flights delayed actually increased by three percentage points; average delays increased another minute to 60 minutes. At San Francisco, where GA flights dropped 36 percent, flight delays were worse by a percentage point, and the average delay grew by eight minutes.

On the other hand, the impact of an infrastructure improvement can be immediately evident. Chicago O’Hare opened a new runway and a runway extension in 2008, and its delays from 2007 to 2009 dropped 12 percent. A new runway opened at Washington, D.C.’s Dulles International Airport in November 2008, and delays have already responded, dropping by 7 percent since 2007. GA operations dropped significantly at Chicago and Dulles as well—39 percent and 28 percent, respectively—but the factor driving the delay reduction was infrastructure improvement.

Why is it that about one out of every three flights in New York still is delayed, and the delays are even longer than in 2007? (Nationally, the figure is one out of every five flights.)

The Bureau of Transportation Statistics breaks down the causes of delays into several categories, including air carriers, severe weather, the NAS, security, and previous aircraft arriving late. These categories are only marginally helpful, as they only give a general picture of delays and in certain instances are subject to the judgment of the carrier reporting the delays.

However, the one category that would include congestion from GA aircraft, “National Aviation System Delay,” actually has increased since 2007, even though GA activity at major airports across the country has dropped significantly. Nearly one fifth of all delays are reported as circumstances within the airline’s control.

To realize any meaningful reduction in delays, the FAA must focus on NextGen ATC modernization initiatives, ATC procedures, new runways where feasible, and air carrier scheduling practices during peak travel periods. Focusing on GA as the proximate cause of delays not only lacks credibility, it also detracts from solving the real causes of delay. Let’s not squander this opportunity to move forward and make the necessary improvements to the NAS and air traffic control system.

Ken Mead is former inspector general of the U.S. Department of Transportation.