Phenom 300 debut

Airline-bred systems and more power make for an ultimate single-pilot bizjet

Although American business jet manufacturers are reeling from the recession’s sting, the same can’t be said for Brazil’s Embraer. Sure, sales are down, but Embraer forges ahead with its new line of business jets, racking up sales that mainly take market share from Cessna’s Citations and Hawker Beechcraft’s Hawker jets. First came the Phenom 100, which was introduced in 2005 and certified in 2008. Today, more than 100 of the six-seat, 390-knot airplanes are in service. (For more information on the Phenom 100, see “View to a Thrill,” June 2009 AOPA Pilot.)

Now comes the Phenom 300, which is a large incremental step up from the Phenom 100. The 300, certified in December 2009, is a larger, faster, longer-legged airplane that’s aimed straight at the niche occupied by Cessna Citations CJ3 and CJ4. The airplane reflects a number of improvements and new features, some of which were added as a result of resolving problem areas with the Phenom 100.

Now comes the Phenom 300, which is a large incremental step up from the Phenom 100. The 300, certified in December 2009, is a larger, faster, longer-legged airplane that’s aimed straight at the niche occupied by Cessna Citations CJ3 and CJ4. The airplane reflects a number of improvements and new features, some of which were added as a result of resolving problem areas with the Phenom 100.

To call the Phenom 300 an enlarged version of its predecessor would be a mistake. It’s a clean-sheet design, Embraer says, with a different type certificate, largely different systems, and a vastly improved cabin. And while the Phenom 300 has swept wings, can cruise at a claimed 453 knots, has twice the thrust, and weighs 8,000 pounds more than the Phenom 100, Embraer has certified the airplane for single-pilot operations. That makes it one of the larger, more capable single-pilot jets on the market.

The key to making the Phenoms single-pilot-friendly merges neatly with the airplane’s overall design philosophy—to make the cockpit ergonomics and airplane systems, service, and maintenance as simple, intuitive, and reliable as those of an airliner. Which makes sense because Embraer’s recent background is, first and foremost, as a builder of a wide range of popular commuter and regional jets (with some models, the “E-Jets,” having seats for 70 to 120 passengers). Business jets may be new to Embraer, but they benefit from the company’s design culture. I visited Embraer’s factory in São José dos Campos, Brazil, for an introduction to the 300, including 1.5 hours of dual instruction with Marcio Miranda, an Embraer instructor pilot.

What’s new

Turbine Edition Table of Contents

- Phenom 300 Debut

- Don’t Hold Your Breath: Oxygen and Altitude

- What It Looks Like: Emergency Oxygen Systems

- Consciousness Countdown: Time of Useful Consciousness

- Fear of Flameout: How Flying Low Can Rob Endurance

- Turbine Profile: Robert Luketic

Many of the Phenom 300’s differences from the Phenom 100 can be seen during the preflight walkaround. Most obvious is the Phenom 300’s use of bleed-air ice protection. The wing and horizontal stabilizer leading edges, as well as the engine nacelle leading edges, use heat routed from the engines to prevent ice from forming. The Phenom 100 uses bleed air to inflate conventional wing de-ice boots. The extra power from the 300’s Pratts make this possible; in the Phenom 100, use of bleed air causes large drops in thrust.

The 300’s dual air data probes do away with the conventional plumbing involved in sampling and sending ram air and angle-of-attack information to the ship’s air data computers. Instead, an electronic interface does the job. This, Embraer says, eliminates pressure lags, does away with pressure checks, obviates the need for a separate angle-of-attack vane, simplifies maintenance (the units can be dismounted and remounted without the need to disconnect and reconnect pneumatic tubing), and saves weight.

Single-point refueling is standard with the Phenom 300, and it’s accomplished using a fueling panel forward of the right wing root. You hook up the fuel hose, dial in the amount of fuel you want, and fueling stops automatically when the target amount is reached. Maximum fuel capacity is 798 gallons, and Embraer says that topping off empty tanks takes less than 12 minutes using this method.

Single-point refueling is standard with the Phenom 300, and it’s accomplished using a fueling panel forward of the right wing root. You hook up the fuel hose, dial in the amount of fuel you want, and fueling stops automatically when the target amount is reached. Maximum fuel capacity is 798 gallons, and Embraer says that topping off empty tanks takes less than 12 minutes using this method.

Carlos Filho of the Phenom product strategy group pointed out that the 300’s spoiler system (something else not on the Phenom 100) incorporates dual functions. In flight, the spoilers are used to augment aileron inputs. After the airplane lands and generates weight-on-wheels signals, the inboard spoilers deploy automatically, serving as ground spoilers to help slow the airplane.

Which brings up the carbon, brake-by-wire anti-skid braking system. Here, Embraer has taken a lesson from complaints about the Phenom 100’s super-sensitive, grabby brakes. The 300 uses a new brake control unit (BCU) that compares braking inputs from each of the main gear brakes—when both brakes are applied—and modulates them so as to create a smoother, more symmetrical braking action. The BCU also incorporates control laws that prevent tire bursts; for example, should you land with brakes applied, the BCU will let the wheels roll. Filho said that the new BCU will be retrofitted to the Phenom 100 fleet.

Go ahead and laugh, but the next stop on the walkaround was at the external lavatory service ports. Undo the cover latches, hook up, and the contents of the flushing toilet are but a memory. This handy feature—again, borrowed from the E-jets—means no more unlucky pilots carrying “baggage” on a weaving, danger-charged voyage down the length of the cabin and out the airstair door. And there’s another service port for uploading new “blue water” from the outside—no muss, no fuss.

Go ahead and laugh, but the next stop on the walkaround was at the external lavatory service ports. Undo the cover latches, hook up, and the contents of the flushing toilet are but a memory. This handy feature—again, borrowed from the E-jets—means no more unlucky pilots carrying “baggage” on a weaving, danger-charged voyage down the length of the cabin and out the airstair door. And there’s another service port for uploading new “blue water” from the outside—no muss, no fuss.

Another noteworthy feature is the Phenom 300’s ventral rudder control (VCS). This is a small, servo-actuated mini-rudder that’s designed to improve lateral stability, and functions automatically via air data inputs once airspeed reaches 60 KIAS on the takeoff run. The VCS is there to dampen any yaw-roll coupling motions (i.e., Dutch roll) when the yaw damper is off. With the yaw damper engaged, the ventral rudder locks in trail. A not-so-small side benefit is that having the ventral rudder lets you dispatch the airplane without a functioning yaw damper.

Strapping in

Anyone familiar with Garmin’s G1000 avionics suite will feel at home in the 300’s front office. Embraer’s three-screen G1000 system—the “Prodigy”—is customized to integrate with the airplane’s systems, and includes a number of features you’d expect in a modern business jet, among them: caution and alert annunciations; system synoptic pages; keyboard data entry (plus redundant data entry on each screen’s bezel); synthetic vision with terrain awareness warning system (TAWS) alerts; plus Garmin’s GWX 68A vertical-profiling weather radar. TCAS II is available as an option, and so is XM WX Satellite Weather datalink service.

Anyone familiar with Garmin’s G1000 avionics suite will feel at home in the 300’s front office. Embraer’s three-screen G1000 system—the “Prodigy”—is customized to integrate with the airplane’s systems, and includes a number of features you’d expect in a modern business jet, among them: caution and alert annunciations; system synoptic pages; keyboard data entry (plus redundant data entry on each screen’s bezel); synthetic vision with terrain awareness warning system (TAWS) alerts; plus Garmin’s GWX 68A vertical-profiling weather radar. TCAS II is available as an option, and so is XM WX Satellite Weather datalink service.

In the event an engine loses power after V1, an automatic thrust reserve (ATR) feature kicks in. ATR looks for a difference in fan speed of 20 percent or more between the two engines. Should this happen, the thrust of the operating engine is boosted by 5 percent (about 170 pounds), helping the climb rate during the rest of the takeoff profile.

Engine start is super simple—just rotate the start switches to the Start position, then release them. In keeping with a single-pilot-friendly design objective, there are no switches to the right of the copilot’s control yoke. This puts all switches within easy reach of the left-seater. After the start come the usual checklist items, including checks of the annunciators—there are aural callouts for engine fires, smoke detection, and faults in the ice-detection and stall-protection systems—and any caution and alert system callouts. Then it’s time to go through the Prodigy’s preflight setup.

This involves using a mnemonic: Fly The Line, Run With Speed. Fly stands for entering the flight plan. The reminds you to enter the outside air temperature; the FADECs will use this for backup information. Line stands for entering the landing field’s elevation, which is required to set the pressurization system. Run is for turning the radar to the Standby position so the antenna won’t hit its stops during the taxi. With is for entering weight information, and Speed is a reminder to enter the takeoff V-speeds.

Flying at 450 and 300

Taxiing is a breeze with the new brake system. The Phenom 100’s brakes were designed to maximize braking power, but doing this meant independent systems for each main gear. The 300’s braking is smooth, and so is the steering. With three passengers, our takeoff weight came in at 16,038 pounds, so V1 was 102 KIAS, VR was also 102 KIAS, V2 was 112 KIAS, and our VFs for the final segment of the takeoff was 128 KIAS. The proper takeoff configuration can be verified by pushing a Takeoff Configuration button on the center pedestal. If the flaps and trims are set correctly, it’s time to take the active.

Taxiing is a breeze with the new brake system. The Phenom 100’s brakes were designed to maximize braking power, but doing this meant independent systems for each main gear. The 300’s braking is smooth, and so is the steering. With three passengers, our takeoff weight came in at 16,038 pounds, so V1 was 102 KIAS, VR was also 102 KIAS, V2 was 112 KIAS, and our VFs for the final segment of the takeoff was 128 KIAS. The proper takeoff configuration can be verified by pushing a Takeoff Configuration button on the center pedestal. If the flaps and trims are set correctly, it’s time to take the active.

Up came the thrust levers to the TO/GA position, and soon we were off the ground and in a 200-KIAS climb going up at 4,500 fpm. Temperatures were above standard all the way to our target altitude of FL450. The climb rate didn’t really begin to sag until passing through FL310, where static air temperature (SAT) was minus 34 degrees Celsius, or about ISA +12. At that altitude we climbed at 180 KIAS, which produced a 2,050-fpm climb rate. In all, it took us 14 minutes to reach FL450—and that was with a climb restriction early in the process. Approaching FL450, we were still climbing at a healthy 850 fpm.

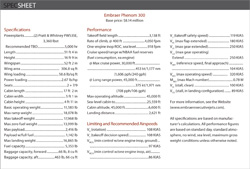

Click the image for a PDF of the Phenom 300 SpecSheet.

Click the image for a PDF of the Phenom 300 SpecSheet.

Max cruise power (85.7-percent N1) at FL450 yielded 418 KTAS in our now ISA +11 conditions, or Mach 0.742. This was right on book, factoring in the temperature. Fuel burn was 432 pph/64 gph per engine, and cabin altitude was a comfortable 6,600 feet, thanks to the 9.3-psid cabin pressurization. The 300 has a cruise speed control button on the glareshield-mounted autopilot/flight control system panel, and by engaging it you capture your current airspeed via automatic, plus-or-minus 15-percent N1 commands delivered by the engines’ FADECs.

To obtain faster cruise speeds, we descended in autoflight to FL300 to take advantage of the denser air. The speed brakes helped the descent, and demonstrated the airplane’s overspeed protection at the same time. So, I pulled the power back to idle, hit the speed brake toggle switch, and pitched over. Soon we were coming down at 10,000 fpm and airspeed was quickly surging to the barberpole. But just before any overspeed alarms sounded, the nose automatically pitched up to smoothly capture our preselected altitude. That’s another neat, workload- and face-saving feature of the Phenom cockpit. Max cruise at FL300 turned in 439 KTAS/Mach 0.72 under our ISA +14 conditions, with fuel burns running at 727 pph/108 gph per side. Had conditions been standard, our speed would have been 451 KTAS/Mach 0.77.

Airwork

I did steep turns and stalls down at 10,000 feet, using the flight director’s command bars to help hold altitude. Control pressures seemed suitably heavy for an airplane of this size, and 50-degree banks and rapid roll rates took less force than I was anticipating—because of the spoiler augmentation, no doubt.

I did steep turns and stalls down at 10,000 feet, using the flight director’s command bars to help hold altitude. Control pressures seemed suitably heavy for an airplane of this size, and 50-degree banks and rapid roll rates took less force than I was anticipating—because of the spoiler augmentation, no doubt.

The stall protection system generates both aural (“stall, stall”) and visual (the red band on the airspeed tape display) warnings of an impending stall, and a stick pusher fires when a full stall is imminent. There is no stick shaker. In a clean configuration at a weight of 14,770 pounds, I went to idle power, held altitude, and let airspeed bleed off. The aural warning came at 106 KIAS, the pusher fired as airspeed hit 91 KIAS, and the nose pitched down automatically. There was little in the way of aerodynamic buffet as the stall approached. When approaching the stall in the landing configuration, buffeting did occur—after the aural warning at 97 KIAS and before the pusher fired at 83 KIAS. There was no rolloff—at least with the stalls I performed. These were slow-deceleration, straight-ahead stalls. Miranda is a test pilot, but I’m not.

On approach—and the future

My time was up, and Brazilian summer weather was closing in—so there was only time for one ILS approach. I hand-flew the command bars during the approach to Runway 15, using a VREF of 108 KIAS down the final approach course and through an 800-foot overcast. I wish I could say that making acceptable Phenom 300 landings requires exceptional airmanship, but alas, the airplane has good manners. If there’s a caution it has to do with the view down the 300’s nose. The windshield gives you a great view of the runway ahead, so I sensed an illusion that the runway was closer than it really was. My temptation was to flare too much and too soon. But the Phenom 300 with full flaps approaches at a rather flat deck angle, so little back pressure is needed to get a good touchdown. After that, it’s a matter of holding the nose off, lest it slam to the pavement. The brakes and ground spoilers do a great job of stopping the ship, so it appears that thrust reversers aren’t necessary.

I didn’t have the chance to sample the Phenom 300’s behavior and performance in single-engine operations. But I am told that, like the Phenom 100, the 300 takes a mighty rudder input to counter yawing forces at takeoff thrust and V1, and during the initial phases of a single-engine climb. I know that in the Phenom 100, those forces reach some 70 pounds of pressure. In the Phenom 300, you can expect to stomp to the tune of 80 pounds of pressure—a real incentive to take up leg presses at the gym. There is no rudder bias system to help fight the yaw, so the drill is to trim like mad until forces are low enough to let you engage the yaw damper, then the autopilot. On the bright side, Embraer claims maximum engine-out climb rates of 2,000 to 3,000 fpm in exchange for your efforts.

The Phenom 300 proves that Embraer is on the march. The company says it has firm orders for about 800 Phenom 100s and 300s, with a claimed 270 orders taken up by the Phenom 300. Some orders are trade-ups from Phenom 100 owners.

Next up are Embraer’s new Legacy 450 and 500 (models MLJ and MSJ), mid-size business jets with seven to 12 seats and ranges from 2,300 to 3,000 nm. These are intended to fill the gap between the Phenoms and the much larger Legacy 600—a super-mid-size jet capable of 3,400 nm. It will be interesting to see how Embraer fares over the next three years, when its business jet fleet is fully developed and the economy rebounds. Wichita will certainly be watching.

E-mail the author at [email protected].