Distraught by the attack on Pearl Harbor and a series of defeats in the Pacific, America desperately needed a victory during the early months of World War II to bolster morale at home and give a shot in the arm to U.S. armed forces struggling to contain Japan’s drive across the Pacific. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt wanted no less than a bombing raid on Japan.

In late January 1942, General Henry “Hap” Arnold asked Lt. Col. James “Jimmy” Doolittle, “What airplane do we have that can take off from a runway 500-feet long and 75-feet wide with a 2,000-pound bomb load and then fly 2,000 miles with a full crew?”

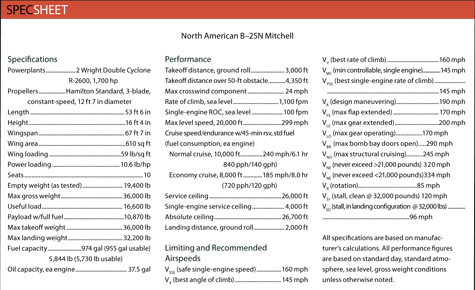

Doolittle replied that only the North American B–25 Mitchell could do that (with additional fuel tanks installed). Thus began the audacious plan to launch a bombing raid against Japan from the deck of America’s newest aircraft carrier, the U.S.S. Hornet, a plan that would begin to restore American pride.

The “Doolittle Raid” established an immediate and superlative reputation for the B–25, and the “medium bombardment and attack aircraft” rapidly became an iconic symbol of American military power. The airplane was used in every theater of the war and by our allies. It is the only U.S. military aircraft named after an individual, Gen. William “Billy” Mitchell, who is considered the father of American air power.

Growing up, Jim Terry, a retired U.S. Air Force major, had spent many hours listening with fascination to the stories his uncle had told of his exploits during the war in a B–25 named Pacific Prowler. They had planned to buy one together, but Terry’s uncle passed away before that could happen. In 2003 Terry purchased a junkyard B–25 on his own, restored it to pristine military configuration, and named it Pacific Prowler in honor of his uncle.

Terry’s airplane was born in 1944 and is a B–25J converted to an N-model. (Doolittle’s Raiders used B models.) In 1962 the airplane was purchased by Tallmantz Aviation and used as a filming platform for 80 motion pictures, including Catch 22, the original Flight of the Phoenix, and Around the World in 80 Days. The airplane, though, was burying Terry in a financial hole, and he couldn’t stand the thought of parking it in the corner of a museum to collect dust. “Pacific Prowler is a flying testament to those who flew the B-25 in combat—to those who returned, and to those who did not,” he says.

Terry eventually decided to keep his airplane flying by sharing it with others wanting to fly a B–25. “Even with the income generated by our training program, it still takes donations and volunteers to keep the airplane in the air,” he says. Pacific Prowler is hangared at the Vintage Flying Museum at Meacham International Airport in Fort Worth, Texas.

Terry offers a relatively economical course that allows pilots to obtain type ratings limited to second-in-command privileges. Although such SIC ratings are not required of co-pilots flying in the United States, they are required when serving as second in command internationally.

This “checkout” program typically takes two days and includes ground school, briefings, preflight inspections, and two hours of dual instruction (one hour at a time). Pilots perform six takeoffs and landings (all from the left seat) and execute a full range of maneuvers. The course costs $5,000. Included also are certain bragging rights. After all, how many pilots can claim to have taken a flight review in a B–25 bomber? The rating even goes on your pilot certificate. The unrestricted type rating with pilot-in-command privileges obviously costs more and depends on pilot ability and experience. It also requires an FAA checkride, while the SIC rating does not. SIC type ratings may be issued for any airplane for which two pilots are required.

Pacific Prowler’s only instructor is Scott “Gunny” Perdue, a U.S. Air Force F-15E driver on furlough from American Airlines. Perdue owned a North American T–6 and is a warbird aficionado. He considers it an honor to instruct in the B–25 and share his enthusiasm for this historic symbol of American air power.

One of Perdue’s recent students was Dean S. Edmonds Jr., of Naples, Florida, an 85-year-old co-inventor of the atomic clock who trained in 1945 as a member of what would have been the Japan Invasionary Force. He credits the atomic bomb for having saved his life as well as hundreds of thousands of others.

Another was Larry Lay, an osteopathic physician and designated medical examiner from Wichita. He wanted to obtain a full-blown type rating in honor of his father, 1st Lt. Allan Lay, who had been flying Hell’s Fire, a B–25D, when he was shot down by Japanese Zeros over Celebes (now Sulawesi) in Indonesia. This was a few months after his son, Larry, was born. Father and son never met.

On board the Mitchell

The B–25 is a handsome airplane with a slight gull-wing appearance. You enter the bomber through fore and aft hatches in the belly, which swing down and incorporate sliding ladders that automatically extend and retract as the hatches open and close. An escape hatch in the ceiling of the cockpit allows for emergency egress in case of a belly landing. Other emergency hatches in the fuselage accommodate other crewmembers.

The cockpit is well organized and logically configured, considering that it is a 1940 design. When sitting in the cockpit, be careful not to raise the landing-gear handle. The gear will retract with or without the engines running. Also, do not close the bomb-bay doors without clearance from a ground signalman or until taxiing. Doing so could bisect anyone standing on the ground between them.

The cockpit is well organized and logically configured, considering that it is a 1940 design. When sitting in the cockpit, be careful not to raise the landing-gear handle. The gear will retract with or without the engines running. Also, do not close the bomb-bay doors without clearance from a ground signalman or until taxiing. Doing so could bisect anyone standing on the ground between them.

As when bringing all large radial engines to life, the procedure requires a chorus of hand movements and is more involved than starting your garden-variety Continental or Lycoming. Your right hand operates the electric primers, energize and engage switches, while the left operates the magneto switches, throttles, and mixture controls. The airplane does not have a steerable nosewheel, and taxiing requires use of differential braking. The brakes, however, are grabby and demand a delicate touch. The rudders are somewhat helpful when taxiing because each is in the prop wash of an engine.

It is important not to allow the nosewheel to turn more than 15 degrees right or left when stopping to hold in position on a runway, a condition indicated by an amber light on the instrument panel. Otherwise, the airplane might head for the weeds after brake release and the application of power.

It is important not to allow the nosewheel to turn more than 15 degrees right or left when stopping to hold in position on a runway, a condition indicated by an amber light on the instrument panel. Otherwise, the airplane might head for the weeds after brake release and the application of power.

As I gazed down the 7,500-foot-long concrete ribbon on a warm Texas day, I was awed imagining what Doolittle must have seen and thought as he stared through the left cockpit window of his heavily loaded B–25 at the incredibly short flight deck of the Hornet.

The plan was for the Hornet to steam within 450 miles of Japan, but the plan unraveled when a Japanese patrol vessel was spotted only 20,000 yards (approximately 12 miles) from the American task force. The cruiser Nashville sank the vessel but not before those aboard might have radioed the position of the task force. Doolittle’s Raiders were compelled to take off immediately, farther from Japan than had been planned. This made it unlikely that the B-25s would have sufficient fuel to reach a safe haven in areas of China not occupied by the Japanese after bombing their targets. None of the 80 Raiders was deterred.

It was 0820 on April 18, 1942, and the Hornet was 824 miles from Tokyo. Doolittle commanded the first B–25 in line for takeoff. From his cockpit window he saw 467 feet of narrow runway and was signaled by a launching officer to “push the throttles fully forward.” The Hornet was steaming at 20 knots into a 30-knot wind, giving aircraft 50 knots of airspeed before beginning to roll.

It was 0820 on April 18, 1942, and the Hornet was 824 miles from Tokyo. Doolittle commanded the first B–25 in line for takeoff. From his cockpit window he saw 467 feet of narrow runway and was signaled by a launching officer to “push the throttles fully forward.” The Hornet was steaming at 20 knots into a 30-knot wind, giving aircraft 50 knots of airspeed before beginning to roll.

The brakes were locked, the flaps were fully extended (as compared to one-quarter flaps for a normal takeoff), and the airplane strained against its shackles. Doolittle and the other pilots set their directional gyros according to the heading of the carrier, which had been written on a large blackboard on the conning tower. When the forward end of the pitching deck reached its point of maximum dip, a flagman signaled Doolittle to go. By keeping his main wheels on painted guidelines, his right wing tip cleared the Hornet’s superstructure by a mere six feet, and the aircraft was “yanked” off the deck at stall speed. All 15 other aircraft followed successfully, although one of the pilots had forgotten to lower his flaps and sank perilously close to the sea before achieving enough airspeed to climb.

One wonders the outcome had there been no wind at the time of launch, or if one of the aircraft had experienced an engine failure between brake release and reaching sufficient speed (145 mph) to safely maintain directional control on one engine.

One wonders the outcome had there been no wind at the time of launch, or if one of the aircraft had experienced an engine failure between brake release and reaching sufficient speed (145 mph) to safely maintain directional control on one engine.

At the beginning of the takeoff roll, you “walk” the throttles until power is set at 40 inches and 2,700 rpm. (Unlike exhaust-driven turbochargers, the B–25 is equipped with two-stage, gear-driven superchargers.)

The Mitchell is undoubtedly the noisiest airplane I have ever flown. The big engines are close to the cockpit and have very short exhaust stacks. Little is done to muffle the “explosions” powering the aircraft from within the 14-cylinder engines. The distinctive crackling and popping sounds they generate when idling on the ground, however, are inexplicably joyful.

At 85 mph you gingerly raise the nose about three degrees while allowing the airplane to lift off on its own in this relatively flat attitude at 120 mph. You then forcefully hold the nose down—it exhibits a strong will to rise—and accelerate as quickly as possible through “no-man’s land” to 145 mph, the minimum airspeed at which an engine failure can be handled without loss of roll and yaw control. Normal climb speed is 160 mph at 30 inches and 2,000 rpm.

Almost everything on the airplane is hydraulically actuated: landing gear, wing flaps, cowl flaps, bomb-bay doors, brakes, and carburetor air-filter doors. (In case of hydraulic failure, there is a separate system to lower the landing gear, and wing flaps can be cranked down manually.)

Heading toward a practice area at economy power (27 inches and 1,700 rpm), I couldn’t help allowing my left thumb to drift onto the Bombs and Guns switches on the left side of the control wheel. Flying a B–25 is exhilarating, and I was itching for a practice high-speed strafing run and to trigger the 50-caliber machine guns mounted on each side of the forward fuselage. Perdue, however, said that I would have to be content with steep turns, slow flight, and stalls. Control forces are heavy, but are tolerable, and the airplane maneuvers nicely. The B–25 burns 150 gallons during the first hour of flight and 120 gallons each hour thereafter.

Heading toward a practice area at economy power (27 inches and 1,700 rpm), I couldn’t help allowing my left thumb to drift onto the Bombs and Guns switches on the left side of the control wheel. Flying a B–25 is exhilarating, and I was itching for a practice high-speed strafing run and to trigger the 50-caliber machine guns mounted on each side of the forward fuselage. Perdue, however, said that I would have to be content with steep turns, slow flight, and stalls. Control forces are heavy, but are tolerable, and the airplane maneuvers nicely. The B–25 burns 150 gallons during the first hour of flight and 120 gallons each hour thereafter.

Doolittle’s Raiders droned and dead-reckoned toward Japan at 200 feet above the North Pacific Ocean. Reduced power was used to maximize range. In addition to stuffing the airplanes with as much fuel as they could carry, each B–25 carried numerous five-gallon cans of fuel that were poured into emptying fuselage tanks. There were no tail guns on early Mitchells. To discourage Japanese fighters from attacking from the rear, black broomsticks were installed to simulate a tail-gunner’s position.Flying low over Tokyo, Doolittle noticed people on the ground waving at them, mistaking the B–25s for friendly aircraft. The Raiders were not attacked by fighters but some were rocked by antiaircraft fire. Upon reaching his target, Doolittle pulled up to 1,200 feet, opened the bomb-bay doors, and dropped his lethal load.

Complete your traffic pattern so as to cross the threshold at 105 mph, and do not idle the engines until in the flare. Landing a B–25 is not difficult, but landing it well is initially challenging. As soon as the mains touch—that’s the easy part—the airplane insists on pitching downward onto its nosewheel before you have a chance to interrupt the process. Eventually one learns the technique needed to hold off the nosewheel and gently fly it to the ground, which is easier said than done in this airplane.

Doolittle’s Raiders didn’t have a chance to land conventionally following the raid on Japan. Because of fuel exhaustion, inclement weather, and nightfall, most of the Raiders bailed out. Others made crash landings. Most of these 80 brave heroes survived the war, but only eight remain to grace our lives.(Eleven were killed or captured, including several executed by the Japanese Army in China. One crew landed in Russia and was held there for one year before they were allowed to return.)

Although the damage inflicted by Doolittle’s Raiders was militarily only a pinprick, it energized American morale. It also caused Japan to fear that additional bombings would follow. As a result, fighter squadrons were recalled from offensive missions to defend the homeland. Japan also rushed its Imperial Navy to begin a premature assault on Midway Atoll in early June 1942. This led to a decisive American victory at the Battle of Midway, the turning point of the Pacific War.

Doolittle himself believed the raid a failure because of the light damage to military targets and the loss of all 16 aircraft, and thought he’d be court-martialed. He was instead awarded the Medal of Honor.

If flying an iconic World War II bomber is on your bucket list, this is an opportunity to do that and have a B–25 type rating emblazoned on your pilot certificate as a permanent souvenir. Further information is available online. Those wanting to enroll in the program will be sent a CD containing training materials and a lengthy USAAF World War II training film, How to Fly a B–25. Watch the film on AOPA Online.

Visit the author’s website.