As pilots, we often think about nervous passengers and how best to calm and reassure them before and during flight.

As pilots, we often think about nervous passengers and how best to calm and reassure them before and during flight.

But what happens when the pilot is the one filled with anxiety and paralyzing self-doubt? Can a once-enthusiastic general aviation pilot recover the joy of flying after his self-confidence has been lost?

David Fern, 48, an electrical engineer in San Diego, California, and an instrument-rated private pilot with 20 years of flying experience, had to confront those uncomfortable questions after a debilitating series of panic attacks convinced him to ground himself nearly a decade ago.

Fern had flown since age 6 with his father, an accomplished GA pilot, and recalls giving a presentation to his second-grade class on the Cessna 150 trainer that included a detailed discussion of its marker beacon receiver. He went on to earn a private pilot certificate in 1990 and an instrument rating in 1992.

“As an engineer specializing in radio communications, instrument flying was infinitely cool to me,” Fern said. “I did as much instrument flying as

it’s possible to do in Southern California, and the thought that it might be dangerous never entered my mind. I never had any difficulty hopping in an airplane and going somewhere, whether I was the one flying or as a passenger.”

But Fern was under increasing pressure at work where the fate of a start-up firm he had joined was uncertain. And at home, discovery of a son’s drug use created a “living hell” of ever-escalating confrontations.

Flying, an activity that required single-minded focus and had previously provided a refuge from such concerns, was suddenly powerless to loosen their grip. Fern found himself worrying obsessively about engine failures, midair collisions, and a long list of other possible emergencies.

Then one day while flying solo and practicing the VOR-A approach into Oceanside Municipal Airport, Fern was seized by an overwhelming anxiety attack that terrified him—even though he had flown the approach dozens of times and the aircraft was operating normally.

“Shortly after I entered the clouds, a wave of incredible panic and terror came over me,” he said. “I felt as if I needed to escape the entire environment of the airplane. I believed that I was completely out of control of the situation that I found myself in. I was afraid of losing control of the airplane, as well as the repercussions of ATC if I got on the radio and told them I was losing control of the airplane.

“I felt a great sense of accomplishment at being able to control my emotions in an airplane again.”

“I couldn’t understand what was happening to me, or why, but I knew it was imperative to fly the airplane first. I started talking to myself out loud, telling myself that there was nothing that needed to be done that I hadn’t done many times before. I got the needles centered where they were supposed to be and completed the approach successfully.

“I had given myself a very bad scare for a reason that was completely beyond my comprehension,” he said. “There was clearly something wrong with me, and I decided that I was unsafe in an airplane cockpit. That flight was to be my last for nearly eight years.”

Panic attacks began taking place elsewhere, too, and always with the same debilitating results. Fern became afraid of being afraid, and the results were wildly unpredictable. Once, while preparing to board a passenger airliner with his wife for a planned vacation, Fern became terrified to the point of becoming ill and was unable to travel.

New perspective

Flying as a GA pilot was something Fern had always loved, and flying as a passenger on airliners was something he needed to do for his profession. Fern started seeing a psychologist who specialized in anxiety disorders and set as one of his central goals returning to the cockpit as a GA pilot.

After six months of therapy, Fern said he was convinced he was making great progress understanding what had been going wrong and taking steps to correct it. He and his therapist decided the best way to confront the problem was to do so directly, and Fern devised a test. He would travel to Warner Springs, California, and take an aerobatic sailplane flight with a glider instructor. If that didn’t make him anxious, nothing would.

“I’d never been upside-down in an airplane,” Fern said. “It was a totally new experience for me, and it would put me in a situation that was sure to cause anxiety. At the time, I hadn’t flown as a pilot in command in seven years.”

Fern said he was nervous as he strapped on a parachute and climbed into the Grob glider’s narrow cockpit. He almost backed out but persevered.

Once the glider was climbing behind the towplane and the instructor was speaking to him in a calm and reassuring way, Fern settled down. The loops and Cuban eights the instructor performed were strenuous and unsettling, but Fern didn’t feel anxious or in danger.

“The thrill I felt was in actually experiencing these new sensations,” he said. “I wasn’t sure I liked the sensations, but I felt a great sense of accomplishment at being able to control my emotions in an airplane again.”

Fern signed up for glider lessons and six months later added a sailplane rating to his pilot certificate.

Fern signed up for glider lessons and six months later added a sailplane rating to his pilot certificate.

“During the training I felt anxious a few times,” he said. “But the magnitude was very small. I’d challenge the reasons for feeling anxious in my mind right at that moment, and the reality was that I was in complete control of the airplane and there was no reason to feel that way. It completely short-circuited the process that previously would have resulted in an anxiety attack.”

The realization was a personal triumph, and it allowed Fern to confront other sources of fear and uncertainty. He realized he was more concerned by his reaction to anxiety than the situation that created the anxiety in the first place.

Fern said he doubted the aerobatic glider flight would have had the same positive result if he had done it immediately after the panic attack in IMC over Oceanside. “At that time I simply wouldn’t have been able to get in the glider because it would have been too terrifying,” he said. “I had to work through the process and understand what was going on in my head, first.”

Happy returns

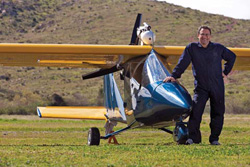

A year ago, Fern returned to flying powered aircraft by purchasing a Titan Tornado II, a light sport aircraft he flies at Nichols Airport, a private airfield southeast of San Diego. He’s also become president of the San Diego Ultralight Association and flew about 60 hours last year. His son’s drug problems have been resolved, too, and that’s relieved a great deal of stress and aggravation as well.

Fern hasn’t returned to instrument flying but says he’ll have no hesitation to do so if it makes sense for personal transportation reasons. Another son has recently become a private pilot, and the family has discussed the possibility of buying an airplane for travel.

Fern said he believes many pilots feel a similar sense of anxiety or nervousness from time to time, but they rarely speak of it because such fears are thought to be a shameful sign of weakness. In fact, he said, such fears can be confronted and defeated, as he managed to do with the help of a professional therapist.

“My anxiety is gone,” he said. “Cognitive therapy changed my life, and gave my love of flying back to me.”

E-mail the author at [email protected]. Photography by Art Brewer.

From the AOPA Medical Services Program

David Fern’s experiences with anxiety after many years of flying—although not an everyday occurrence among general aviation pilots—happens more often than we might think. Anxiety disorders blanket a constellation of symptoms including panic attacks, which can occur when someone experiences something that prompts a response to an underlying phobia. People who are afraid of spiders, for instance, may panic when they run across one. A panic disorder diagnosis is usually made when there have been more than a couple of episodes of panic attacks. Anxiety disorders may be successfully treated with behavioral or drug therapy, depending upon the severity of symptoms.

The FAA handles these disorders conservatively if medications are used long term. Antidepressants and anti-anxiety meds such as SSRIs and benzodiazepines are often effective treatments, but are disqualifying for medical certification. The FAA will want a detailed report from the treating physician, and medications will usually need to have been discontinued for at least 90 days with no recurrence of symptoms before medical recertification can be considered.

—Gary Crump director, AOPA Medical Services Program