Honoring the Tuskegee Airmen

A Stearman’s special history helps tell an important story

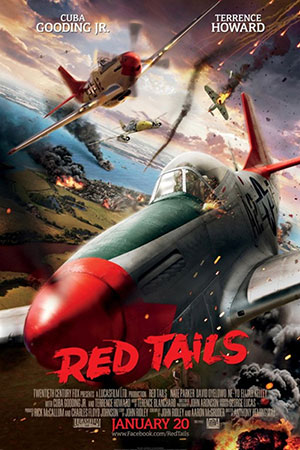

Red Tails take to the screen

George Lucas’ tribute to the Tuskegee Airmen

World War II’s Tuskegee Airmen proved themselves in combat as the military’s first black pilots, earning the nickname “Red Tails” because their fighters’ tails were painted red for easier identification. Filmmaker George Lucas’ tribute to the Airmen—the feature-length movie Red Tails —is scheduled for release on January 20, 2012. It’s based on the experiences of the 332nd Fighter Group, which saw action in Sicily and Italy, and escorted bombers across Europe.

“I’ve been wanting to do Red Tails for 20 years, and we’ve finally got the means to showcase the skill of the Tuskegee pilots,” Lucas said when the production was announced in 2009. “We’re working on techniques which will give us the first true look at the aerial dogfighting of the era.” According to media reports, Lucas is bankrolling the entire $93 million project, $58 million to produce the film and $35 million to distribute it.

“I’ve been wanting to do Red Tails for 20 years, and we’ve finally got the means to showcase the skill of the Tuskegee pilots,” Lucas said when the production was announced in 2009. “We’re working on techniques which will give us the first true look at the aerial dogfighting of the era.” According to media reports, Lucas is bankrolling the entire $93 million project, $58 million to produce the film and $35 million to distribute it.

Academy-Award-winning actor Cuba Gooding Jr., one of the film’s stars, talked about Red Tails at AOPA Aviation Summit in September. “I always am excited when there’s a role in development about a real-life character,” Gooding said, explaining that it heightens his desire as an actor to get the depiction right—especially if the person is still alive. “You get to embody a sense of who that person is, and present that to the world. That’s always really exciting to an actor.”

Gooding starred in a 1995 film, The Tuskegee Airmen. When Red Tails was announced, agents said they didn’t want to use any actors from the original movie. But the Tuskegee story appealed so much to Gooding that he appealed to the director—who, it turns out, had him in mind for the role he landed in the new film. “The first one was a $2 million HBO film. This one was George Lucas’ passion project,” Gooding explained. “It’s a nice bookend piece for the original Tuskegee movie, where I was a pilot.” In this film, his character—Maj. Emanuelle Stance—is an instructor.

Gooding, who does not fly, said he’s spent a lot of time in simulators and around pilots. “The closest I came to actually controlling in flight was a movie I did called Outbreak,” said Gooding, who performed several helicopter takeoffs—but not the landings, he quickly added. “I’d never trained to be a pilot but I’ve been behind the stick of a few Cessnas.”

The veteran actor has not yet seen the film, which is still in post-production. “From the materials I’ve seen, I’m very proud of the accomplishments…the emotional impact that I’ve seen it have on me. [The film] really conveys the tribulations they went through in combat.”

Gooding shared a little inside information, as well: Look for the release of Double Victory ahead of the movie. “Lucas put together a two-hour documentary on the history of the Tuskegee Airmen.”

Several of the original Tuskegee Airmen were on the set every day at an abandoned Soviet air base in Prague, in the Czech Republic, where Gooding filmed for 13 weeks. “They would sit and talk about stories and it would remind them of something…they would tell us more. They were checking our uniforms and moving our belts. If there was anything too heightened in reality they would pipe up,” he said. “There’s a connection,” added Gooding, who is called to stories themed around the African-American experience. “Those stories to me are very attractive—they’re very telling.” —MPC

Photography by the author

There was a lot going through Matt Quy’s mind that steamy August morning as he flew his 1944 Boeing PT–13 Stearman down the final approach to Runway 19 Left at Washington Dulles International Airport. His wife, Tina, sat in the front cockpit. To his left, he could see the Washington Monument in the distance. The wind singing in the biplane’s flying wires confirmed his airspeed: Fast. In a relative way, of course.

“There was an airliner in front of us and one behind us, so I came screaming in, in a dive with the power on,” Quy said. The airspeed indicator read 140 mph. “It was about the fastest it’s ever been.

“There was an airliner in front of us and one behind us, so I came screaming in, in a dive with the power on,” Quy said. The airspeed indicator read 140 mph. “It was about the fastest it’s ever been.

“Coming into Dulles I thought, ‘I sure hope this landing is a good one.’ In the back of my mind I thought, ‘If the landing’s not good, do I go around and do it again?’”

Although good landings are important to him, Quy’s not the kind of guy to obsess about each one. But this landing was different—it would be his last one in the Stearman he and Tina had bought more than six years earlier; they spent three years rebuilding it, and Quy had flown it for three years as a tribute to the Tuskegee Airmen.

A do-over wasn’t necessary.

Several vehicles loaded with photo-graphers met the blue-and-yellow biplane as it cleared the active, but they moved farther away as he taxied onto the ramp at the National Air and Space Museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center. “I said to Tina, ‘Has it hit you that it’s the last moment the airplane will be flying—ever?’ It was kind of surreal,” Quy recalled.

“I sat there with the engine idling. I just didn’t want to cut the mixture. I thought, one last time, I want to hear the engine run.” He pushed the throttle forward and ran the engine up to 1,400 rpm before pulling the mixture to idle cutoff. “That moment, as the prop stopped, the whole month-long journey [to the Smithsonian] passed through my mind, and I realized there was nothing else ahead of us. I just sat there in the airplane, and started to tear up a little bit.”

Discovering history

They had bought the Stearman on eBay as a wreck. While they were rebuilding it, Quy—a captain in the U.S. Air Force—requested the airframe’s Army Air Corps history. “When I got the call from the historian at Maxwell Air Force Base, I knew we had something special.” The airplane’s first assignment was at Moton Field in Tuskegee, Alabama, as a primary trainer in 1944 and 1945. There, it was used to train black pilots in what was then called the Tuskegee Experiment, because military leaders at the time did not believe that blacks could learn to fly and fight.

Tuskegee Airman Leroy E. Eley talks with Stearman owner Matt Quy in Moton Field’s Hangar 1.

Tuskegee Airman Leroy E. Eley talks with Stearman owner Matt Quy in Moton Field’s Hangar 1.

After the war it was released from military service and flew into the 1970s as a crop duster, then sat derelict until the 1990s when it was rebuilt. The Stearman was wrecked in late 2004, and the Quys bought it in 2005.

“When we found out about the Tuskegee Airmen heritage, my wife and I sat down and decided that we’d dedicate the airplane to the Tuskegee Airmen,” and use it to help tell their story, Quy said. They named the airplane Spirit of Tuskegee; painted it in an appropriate scheme; and Quy flew it to airshows around the country, inviting local Tuskegee Airmen to the airport. Then the Smithsonian called.

“I really had no intention for it to go into a museum where it wouldn’t fly,” he said. “For it to go in the Smithsonian was a really tough decision for us, but you know, the Tuskegee Airmen are all getting older, and it’s getting harder and harder for them to come out and tell their story.” The airplane will be a centerpiece of the Smithsonian’s newest museum, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, scheduled to open in Washington, D.C., in 2015. Until then the airplane will be displayed at the Udvar-Hazy Center. “It’s going to be able to tell its story to hundreds of thousands of people each year, so it’s going to a good place.”

Final journey

The Spirit of Tuskegee’s month-long journey from California to the Smithsonian included stops at the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colorado; Minneapolis; EAA AirVenture in Oshkosh; and the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site at Moton Field in Tuskegee, Alabama (see “Fly-Outs: Moton Field”).

Eley taxis out with Quy for a flight in the Spirit of Tuskegee (top). Eley was one of 44 Tuskegee Airrmen to sign the Stearman’s baggage compartment door (bottom). Eley, 84, was training at Moton Field in 1945 when the war ended.

Eley taxis out with Quy for a flight in the Spirit of Tuskegee (top). Eley was one of 44 Tuskegee Airrmen to sign the Stearman’s baggage compartment door (bottom). Eley, 84, was training at Moton Field in 1945 when the war ended.

Bringing the airplane back to Tuskegee was important to Quy, and—between local flights—the Spirit of Tuskegee was on display for a full day where it served during the war. A number of Tuskegee Airmen came out for the occasion, and clearly enjoyed seeing the airplane fly. Whenever possible he invites the airmen to go flying. “It’s a lot of fun to sit in the backseat and watch them fly and think, ‘Here I am flying with a Tuskegee Airman from World War II, one of my heroes, and I just get to sit back and enjoy it.’” Increasingly, however, age keeps most from climbing into the biplane’s forward cockpit.

Leroy E. Eley of Atlanta flew with Quy at Moton Field. Eley, 84, was stationed there in 1945. “When the war ended, all training from my class down—stopped,” he said. Eley finished training as a civilian and became an instructor almost immediately. After 20 years of teaching, he became an FAA inspector, retiring in 1990 after 20 years of service.

Quy said Eley flew as though he had never left the cockpit, and that the veteran pilot critiqued Quy’s touchdown—which started as a wheel landing and became a three-pointer. “He was absolutely correct in his assessment of my landing,” Quy added.

“I finished the whole primary flying school here,” said Oscar Gadson, gesturing at the Moton Field hangars. “My first solo flight was right across that field—it was a grass field at the time.

“The first time I got close enough to touch an airplane was when I climbed in one to learn to fly,” added Gadson, a spry 91-year-old. “[The Stearman] is easy to fly, but it will ground loop in a minute.” He didn’t complete advanced training in the AT–6 Texan, and saw combat in the infantry, then flew general aviation after the war.

Bill Childs, a Tuskegee Airman who helped maintain the aircraft at Moton Field, showed Quy some of his tools—displayed behind protective plastic in a toolbox. Childs, 88, said he paid for the tools. “If you didn’t keep them locked up, somebody would steal them,” he said. “I spent many a day out there [on the ramp]. Each morning we had to preflight [all the airplanes].”

After arriving at the National Air and Space Museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center, Quy removes the Stearman’s 300-horsepower Lycoming R680-13 to replace it with the original 225-horsepower model (left). Bill Childs, 88, of Tuskegee, Alabama, helped maintain the aircraft at Moton Field during World War II; that’s him standing at right in the photo behind him (right).

After arriving at the National Air and Space Museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center, Quy removes the Stearman’s 300-horsepower Lycoming R680-13 to replace it with the original 225-horsepower model (left). Bill Childs, 88, of Tuskegee, Alabama, helped maintain the aircraft at Moton Field during World War II; that’s him standing at right in the photo behind him (right).

Childs said he worked primarily on the Stearmans, which were “not hard to work on. I hated putting new wings on, after somebody ground looped—and that did happen. You had to re-rig everything.”

In Alabama Quy also added a few more airmen’s signatures to the inside of the Stearman’s baggage door—another effort to honor the airplane’s Tuskegee legacy. “I think we had 44 signatures when we finished up.”

“It takes a short while, but it comes back to you,” Eley said after flying the Stearman. “I loved to do snap rolls in the Stearman, and Cuban eights. On this flight I just did straight and level, and some turns.”

Epilogue

All told, the journey to Washington took some 74 flight hours, which Quy said included a lot of local flights. He logged about 340 hours in the airplane since its refurbishment was completed in 2008. Although its military and crop-dusting logs were gone, he estimates 5,500 total hours on the airframe.

. As his journey with the historic biplane winds down, Quy enjoys a sunset flight over Moton Field.

. As his journey with the historic biplane winds down, Quy enjoys a sunset flight over Moton Field.

At the Udvar-Hazy Center, the Spirit of Tuskegee was the first aircraft worked on in the new Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar. The airplane’s 300-horsepower Lycoming R680-13—added during its crop-dusting years—was replaced with a 225-horsepower Lycoming R680-17. “It’s so neat to see it with that stock engine on there,” Quy said. Disc brakes and the tailwheel also were replaced with stock components, and the modern radio and transponder were removed.

Two years ago, Quy tucked a photo of his wife above the magneto switch in the rear cockpit. She likes to accompany him on local sorties but not long cross-countries, he said. “I just wanted to have something with me, something of her in the airplane.” He left the photo in the airplane.

Tina, too, was sad to part with the Stearman. “She said she’d really miss going for sunset flights on nice, calm evenings.”

The engine will fly again, however. The Quys are rebuilding another 1944 PT-13 that will be painted to commemorate POWs and MIAs. As he contemplated placing the Spirit of Tuskegee in the Smithsonian, Quy saw a documentary about prisoners of war in Vietnam. “That’s when it hit me. I thought it would be so cool to be able to commemorate these guys. I feel that we as Americans owe so much to the people who have served our country in the past, and kept our country free.”

Given the opportunity, Quy would “absolutely” repeat the Tuskegee Airmen tribute. “Aside from the flying, I think it’s really made me a better person, and it’s allowed me to have insights into something that I never had exposure to. Growing up as a white boy in Minnesota, I never had experience with racism. I was very fortunate that I didn’t have to fight through a lot of adversity to get to where I wanted to be.

“I feel very fortunate that we were able to spend this time with so many Tuskegee Airmen and get to know them as friends over the years,” he said. “It’s been magical and absolutely amazing…it’s been a lot of fun, and an honor. I feel very lucky.”

Email the author at [email protected].