The Australian landscape photographed from the Kungkalahayi lookout in Purnululu National Park.

The Australian landscape photographed from the Kungkalahayi lookout in Purnululu National Park.

Photography by the author

Skimming along over crocodile-infested waters in a well-worn Cessna, watching the wide, green expanse of mangroves and coils of tropical rivers unfold, I ask myself, like all well-trained pilots, where would I put her down if I had an engine failure now? A daunting thought indeed.

The durable Cessna 402 on arrival at the Outback strip at Mount Borradaile

The durable Cessna 402 on arrival at the Outback strip at Mount Borradaile

Unlike in most parts of the world there is no sign of human life below, just thousands of square miles of lost universe. I’m in northern Australia looking anxiously for a red dust airstrip in Arnhem Land about 300 miles east of Darwin near Kakadu National Park. This Aboriginal-owned expanse is made up of wild coastlines, deserted islands, rivers teeming with fish, lush rainforests, soaring escarpments, and savannah woodland. This land is one of the last great, unspoiled areas of the world. Its small population is predominantly indigenous, its traditional Aboriginal culture remains largely intact.

The didgeridoo wind instrument originated in Arnhem Land, and the area is also world renowned for its distinctive, authentic Aboriginal art. This is not the typical image most people have of Australia. Here in the tropics there are just two distinct seasons: the wet (November to April) and the dry (May to October). The time to visit is “the dry,” when clear blue skies, balmy days, and chilly nights prevail. In contrast to the bone-dry deserts of the central and western parts of the country, “the wet” is influenced by big low-pressure systems that bring thunderstorms and spectacular lightning shows. Later, heavy rains create tumescent river systems that flood vast areas of wetland. In the dry season, rivers shrink to form billabongs (water holes) and wildlife becomes abundant. Remote, fly-in wilderness camps accommodate intrepid travelers who come to marvel at the extraordinary bird life, fish for giant barramundi, traverse the rivers for freshwater and estuarine crocodiles, and climb into caves to search for mystical Aboriginal rock paintings that have existed for thousands of years.

Aboriginal rock paintings have existed for thousands of years. Shown here is the “Rainbow Serpent” in Kakadu National Park, the traditional lands of the Gagudju people of Arnhem Land.

Aboriginal rock paintings have existed for thousands of years. Shown here is the “Rainbow Serpent” in Kakadu National Park, the traditional lands of the Gagudju people of Arnhem Land.

From the air

Airplanes here are used like off-road vehicles. And often look like them. Single and light-twin workhorses reliably operate into rough-hewn strips in areas that have few paved roads. Flown by old hands, some reminiscent of Mick “Crocodile” Dundee, who have fallen in love with this territory—or young Aussies looking for adventure—they often facilitate the only means to an authentic Outback experience. Special permission is required by the Aboriginal Councils that manage Arnhem Land to gain access. These lands are sacred, and many sites are off limits to non-Aboriginal people.

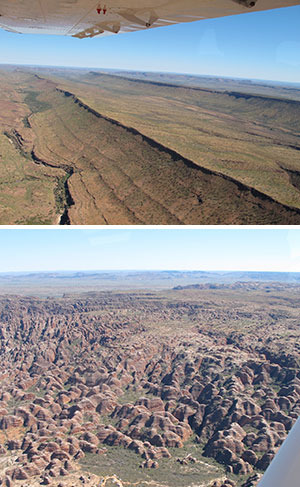

Ancient rocks measure their age in billions of years (top); vast wetlands are the home of teeming wildlife and ancient peoples (bottom)

Ancient rocks measure their age in billions of years (top); vast wetlands are the home of teeming wildlife and ancient peoples (bottom)

At the Mount Borradaile airstrip I am met by Max Davidson. He lays out the ground rules to ensure my passengers and I don’t disrespect local customs and ancient traditions. Here in this pristine wilderness there is eeriness in its solitude. The walls of secluded rock shelters are decorated with innumerable pictures documenting traditional Aboriginal life over 50,000 years.

To reach these sublime galleries we travel by flat-bottom aluminum boat (“a tinnie” in the Aussie vernacular) through the wetlands and under the exotic screeches of unique birds such as the crane-legged jabiru, the majestic sea eagle, and around giant colonies of magpie geese. More than 200 species of birds can be seen here as well as flora and animals like the rock-hopping wallaby and the scavenging dingo.

But soon it’s time to move west to The Kimberley, an environmental battleground the size of California. This is a region of breathtaking beauty, fragile biodiversity, and mystery that even few Australians have visited. Mining and energy companies are locked in a high-stakes battle with fervent environmentalists. Most of it is only accessible by four-wheel drive, by boat along its spectacular coastline, or by airplane.

The spectacular Osmond Ranges (top); the Bungle Bungle (bottom)

The spectacular Osmond Ranges (top); the Bungle Bungle (bottom)

Our steed of choice for this sector is the Australian-built Gippsland Airvan, a high-wing utility aircraft powered by

a turbocharged Lycoming TIO-540-AH1A engine. The Airvan is one of Australia’s most successfully designed and built airplanes now exported to more than 20 countries. Simple to fly, ruggedly constructed, and with a hefty payload, the aircraft was built for Outback conditions.

From the pretty rural town of Kununurra we fly south over the Argyle diamond mine (one of the world’s major diamond suppliers, including the rare pink and champagne diamond), across the spectacular Osmond Ranges—a line-up of giant stone and earth waves, frozen in time. As savannah grasslands break into steep bluffs and stark gorges we arrive over the Bungle Bungle Range in the remote Purnululu National Park. This natural phenomenon of striped sandstone domes is estimated to be 350 million years old. Not discovered by the outside world until 1982, it is now a World Heritage site.

Banking steeply, we look down along the magical rows of beehive-shaped sedimentary formations, many still in the making, as erosion by centuries of weathering continues. It is impossible to compare the Bungle Bungle to any other landscape you may have seen—anywhere.

We fly north now and skirt the shores of Lake Argyle, an impressive, man-made reservoir. Fed by the Ord River, it traps the deluge of “the wet” and controls the flow to rich farmland below the dam. Crocodile hunting was suspended here in 1971, and the estimated croc population of 35,000 in this lake alone is testament to the success of a sustained program to rehabilitate the species. We fly farther west in search of the wonders of The Kimberley.

Circumnavigate Australia

Air Safari International, a small-group flying tour service, will host a circumnavigation tour of Australia in 2012. The first leg starts in Brisbane in late March. It tracks south along the coast for 3,300 nm arriving in Perth. The second leg continues a clockwise track for 4,200 nm and returns to Brisbane in early May. The trip is designed for pilots and non-pilots. Spots are currently available on both legs. For more information, visit the website.

White, predominately British explorers came to this region in the 1800s. But the Aboriginal people had survived the harsh climatic conditions as nomads for millennia. They are the world’s oldest living human society; they recorded their history in song and their culture in rock art. One of the many reasons to come to this inaccessible part of the world is to explore the mystery of two distinct forms of Aboriginal rock painting. The less-esoteric Wandjina rock art, painted in the past 3,500 years, is directly related to living Aboriginal culture. The mysterious Bradshaw or Gwion-Gwion paintings are thought to be at least 17,000 years old, perhaps more than 25,000 years old. (Better-known Egyptian hieroglyphs are a mere 5,000 years old.) No one knows who painted these hauntingly beautiful, figurative images on vertical rock faces. Slim, elegant people are finely portrayed in deep red pigment, elaborately adorned with ceremonial headdress, armlets, and sashes in a trance-like dance. Gwion artists left their paintings in deliberately hidden rock shelters with barely a trace of their existence. Archaeologists speculate that these paintings could hold a vital clue to humanity’s distant past.

The revered nineteenth-century Australian bush poet A.B. “Banjo” Paterson wrote of his love of country and the beauty of the land:

“Where the air so dry and so clear

and bright

Refracts the sun with a

wondrous light,

And out in the horizon makes

The deep blue gleam of the

phantom lakes.”

How more profound would have been Paterson’s prose if he’d seen it from above?

Patrick J. Mathews, AOPA 1134012, of Indian Wells, California, is a 1,750-hour, instrument-rated private pilot. He is a freelance writer who owns a 1993 F33A Beechcraft Bonanza.

The author’s trek began at Jabiru, Northern Territory, in the top end of Western Australia and traversed southwest to The Kimberley, a remote and rugged frontier with few signs of human development except an occasional road.

The author’s trek began at Jabiru, Northern Territory, in the top end of Western Australia and traversed southwest to The Kimberley, a remote and rugged frontier with few signs of human development except an occasional road.