Photography by Mike Fizer

To find the American Champion factory, head southwest from Milwaukee, away from the frenetic highways along the Chicago corridor, and west to the quiet country roads through Rochester, Wisconsin. Even in this town of 1,100 people, few know there is an airplane factory making tailwheel models on the farm next door.

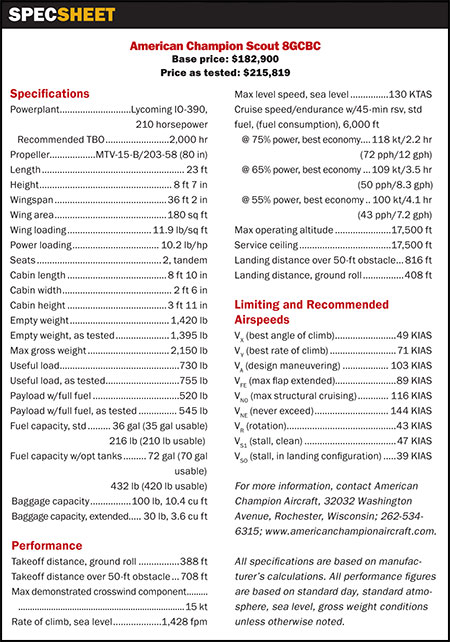

The Alaskan Bushwheel tailwheel (top) provides precise and simple ground handling for a variety of runway conditions. The injected Lycoming engine uses a forward-facing fuel servo. The large Brakett air filter (middle) is retained and mounted directly to a revised airbox. A lightweight, Plane-Power alternator provides up to 70 amps of electric power. The stainless exhaust (bottom) features a four-to-one collector with equal length headers maximizing the installed horsepower.

The Alaskan Bushwheel tailwheel (top) provides precise and simple ground handling for a variety of runway conditions. The injected Lycoming engine uses a forward-facing fuel servo. The large Brakett air filter (middle) is retained and mounted directly to a revised airbox. A lightweight, Plane-Power alternator provides up to 70 amps of electric power. The stainless exhaust (bottom) features a four-to-one collector with equal length headers maximizing the installed horsepower.

Past the cornfield, beside the soybean field, aeronautical engineer Jody Bradt quietly prepares the Scout company flagship for a test run with the 210-horsepower Lycoming IO-390. It’s been 18 months from the start of the project to now, and Bradt hasn’t taken a single vacation day. During earlier tests, the big engine, already a hit with the Experimental community and finally certified in 2009, was running hot.

Everything about the nose of the tandem-seat Scout had to change to make room for the 390; the cowling was made bigger, but the engine still ran hot. First a single oil cooler was added, and then two, but finally two modest-sized, seven-row coolers solved the problem. Today, there will be a slight oil leak from one of the coolers, but not before the more powerful Scout has shown what it can do. (The cooler was easily replaced, solving the leak problem.)

Because the engine is more powerful, the aircraft benefits from larger, more effective tail control surfaces. Fortunately, American Champion’s owner Jerry Mehlhaff and his son, Jerry Mehlhaff Jr., had a solution from a previous project. A larger tail had been developed for the Scout water bomber—a project based on having five or six Scouts simultaneously attacking newly detected fires. That tail is now on the Denali Scout, the name for this new model.

There’s always competition among company employees to name new models, and none submitted more names than Bradt, but ultimately the decision was Mehlhaff Senior’s. He is aiming at the Alaskan bush pilot who needs to rocket off a gravel bar, and against competitors who switched their single-engine bush plane models to 200-horsepower engines some time ago.

American Champion now becomes the first original equipment manufacturer to offer the Lycoming IO-390. Supplemental type certificates also clear the way for its use on Cessna Cardinals and Mooney M20E, F, and J models. Other STCs are in the works. It came along just at the right moment for American Champion’s needs, but also during an economic recession that is delaying the engine’s adoption.

Not even 300 feet

The shrouded exhaust provides alternate air and ample front and rear cabin heat.

The shrouded exhaust provides alternate air and ample front and rear cabin heat.

Bradt taxies to a point 300 feet from the end of the runway and spins around, showing me where I should set up a video camera. I carefully step 30 feet into the soybean field, avoiding the newly sprouted plants, to secure the tripod in the soft soil. With the application of full power, Bradt raises the tail slightly for a scant few seconds during the roll, and the Scout is airborne well before reaching me. At maximum gross weight, Bradt says later, the aircraft will need 350 feet. The previous 180-horsepower model, the company’s website says, needs a ground roll of 490 feet. After a circuit above a cornfield to the west, Bradt lands and stops well before my 300-foot location. He hadn’t practiced short-field landings prior to that one.

Next it’s my turn. Noting that Bradt raises the tail as part of the takeoff procedure, I start the takeoff roll and as I am thinking about raising the tail, the aircraft takes off. It was frustrated waiting for my slower plan. Now we’re climbing at better than 1,500 feet per minute. During earlier air work I noticed Bradt was especially attentive to the rudder pedals during stall recovery, and I experience a 10-degree wing drop following a full stall. Because I am unaware that level attitude is actually achieved when the nose is four degrees down, we’re at 6,000 feet by the time my maneuvers are finished.

Equipped with a greenhouse window on the top of the cabin (left), the increased field of view is useful to see ahead while maneuvering. The electrical panel is located above the pilot’s left shoulder. A large cabin door and entrance step provide easy access to the 31-inch cabin. The Scout can be equipped with a quick removable rear seat and a fully opening left window.

Equipped with a greenhouse window on the top of the cabin (left), the increased field of view is useful to see ahead while maneuvering. The electrical panel is located above the pilot’s left shoulder. A large cabin door and entrance step provide easy access to the 31-inch cabin. The Scout can be equipped with a quick removable rear seat and a fully opening left window.

Bradt then maxes out the power to demonstrate top speed, which turns out to be close to his predicted 155 mph. Throttled back to 75 percent power, we do a more modest 138 mph. At maximum power, the engine can use as much as 17 gallons per hour, Bradt said, but throttled back to low power settings, it can sip as little as seven. It has a time between overhaul of 2,000 hours.

Careful with the hardware

Note the electric fuel pump switch and vernier mixture,two subtle changes for the 210-horsepower engine. A variety of equipment options are available; avionics vary from none to the latest Garmin GTN 750.

Note the electric fuel pump switch and vernier mixture,two subtle changes for the 210-horsepower engine. A variety of equipment options are available; avionics vary from none to the latest Garmin GTN 750.

This particular Scout is one of a kind, the only one in the world with a 210-horsepower engine. It is still needed to certify the engine installation, but it is already sold, so the pressure is on. I decide not to land it on this gusty, crosswind day. After a perfect three-point touchdown, Bradt said he notices no difference in landing characteristics between this and the 180-horsepower Scout, despite the 30 extra pounds up front that result from the engine, its accessories, mounting hardware, and the new cowling. The 180-horsepower Scout will continue to be offered.

The senior Mehlhaff said the Denali Scout used for testing has a price of $205,000, although he is discounting it because of the testing hours to $199,000. Part of the price can be attributed to JPI’s EDM-930 engine monitor ($9,200 installed) and the Aspen Avionics Evolution 1000 Pilot flight display system ($7,495 installed). There is also a Garmin 496 GPS for navigation.

Morning fog at the American Champion factory in Rochester, Wisconsin, had lifted and was scattering when these photos were taken. Large patches remained to provide a surreal backdrop. The larger tail, copied from a previous design for a firefighting Scout water bomber, was needed to provide better control with the increase in horsepower. The aircraft is stable enough for hands-off flight.

Morning fog at the American Champion factory in Rochester, Wisconsin, had lifted and was scattering when these photos were taken. Large patches remained to provide a surreal backdrop. The larger tail, copied from a previous design for a firefighting Scout water bomber, was needed to provide better control with the increase in horsepower. The aircraft is stable enough for hands-off flight.

The Mehlhaffs are not done tweaking the Scout. Watch this space for news of a diesel-powered Scout yet to come.

For now, pilots with worries about hot and high flying conditions, very high terrain elevations, or just rough and tough unimproved—or nonexistent—runways should take a look, but don’t ask to speak to Jody Bradt. He’s on a well-deserved vacation, at last.

Email the author at [email protected].

Postscript: A second flight

Air-to-air photo shoots conducted by AOPA Pilot Senior Photographer Mike Fizer shouldn’t be called early morning or sunrise shoots: They are middle-of-the-night shoots. The alarm went off at 3:45 a.m. Fog between the hotel in Racine, Wisconsin, and Rochester, Wisconsin, was so thick the car wipers were needed to get through it. The flight provided a second look at the Denali Scout. The takeoff at 5:45 a.m. went more smoothly for me than the one weeks earlier. Rather than try to raise the tail, I neutralized the stick shortly after beginning the takeoff run, knowing this more powerful Scout would be in the air before I knew it. With two aboard, we were off in 400 feet. Aeronautical engineer Jody Bradt was told to go as fast as he liked as he led our photo formation of two aircraft in a Citabria High Country. He took off first to get a head start, and needed it. I caught up quickly despite waiting for him to not only clear the runway, but depart a quarter-mile from the factory airport. With more power than I needed, I first stayed even with him, but 100 feet behind to see what power setting matched the High Country’s speed; it was half throttle for the Scout. The early morning fog had lifted a couple thousand feet and drifted to one side of Rochester, where we could fly over it briefly for photos. During one 360-degree circle, factory test pilot Dale Gauger, sitting behind me, noticed we caught our wake turbulence after completing the first circle and congratulated me. I took my hands off the stick (I was leading the formation after a lead swap), and showed Gauger it was the airplane maintaining bank and altitude, not me. The Scout has always had that sort of stability; now it also has the power and speed to be an efficient bush hauler. —AKM