Avionics: Traffic systems

Traffic roundup—Tools to help you see other aircraft offer impressive benefits

Traffic Alert and Collision Avoidance Systems (TCAS) used to be confined to airline cockpits, cost a fortune, and perform identically. Today, however, that’s changing as a variety of collision avoidance tools (though not necessarily TCAS) have made their way into thousands of general aviation cockpits. And instead of being one size, and fitting one FAA specification, the new equipment ranges widely in cost, capability, information collection methods, and how it is displayed. Combined with the fundamental changes in the air traffic control system being brought about by NextGen—the Next Generation Air Transportation System, which relies on GPS-based ADS-B technology rather than today’s ground-based radar—cockpit traffic warning equipment is sure to continue evolving rapidly.

Passive portables

The most basic and least expensive of today’s traffic warning tools are portable and passive. Pilots typically mount them on glareshields, and a network of ground-based radar does the interrogation of airborne airplanes. The portable traffic warning units pick up the reply data and display the positions of other aircraft relative to the host aircraft on the traffic units themselves, or moving-map GPS screens, or multifunction displays (MFDs) linked to the traffic warning systems.

The most basic and least expensive of today’s traffic warning tools are portable and passive. Pilots typically mount them on glareshields, and a network of ground-based radar does the interrogation of airborne airplanes. The portable traffic warning units pick up the reply data and display the positions of other aircraft relative to the host aircraft on the traffic units themselves, or moving-map GPS screens, or multifunction displays (MFDs) linked to the traffic warning systems.

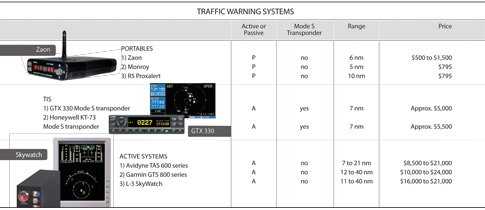

Portable collision avoidance systems such as those made by Monroy, R5, and Zaon range in price from about $500 to $1,500, and they can be hard-wired to the aircraft’s electrical system, plugged into 12-volt power outlets, or run on internal batteries. (Zaon also sells a Bluetooth module for $195 that allows wireless transmission of traffic information to other portable displays within the cockpit.) The downside to the portable systems is that they generally don’t provide aural distance and azimuth callouts (some simply report “Traffic!”). And others with tiny screens require that pilots focus their attention inside the cockpit for threat warnings at the very time they should be looking outside for potential traffic conflicts.

Integrated suites

More tightly integrated PFD/MFD combinations such as Avidyne’s Entegra and Garmin’s G500/600/1000 suites and Honeywell systems typically work in combination with Mode S transponders that get signals from the FAA’s Traffic Information System (TIS), a radar network in terminal areas that interrogates aircraft transponders and compiles and transmits the information to aircraft.

The integrated avionics suites display TIS information graphically on MFDs (and sometimes PFDs, too). These traffic systems can track multiple threats, and they are often linked to graphical terrain and weather displays that greatly enhance pilot situational awareness.

The integrated avionics suites display TIS information graphically on MFDs (and sometimes PFDs, too). These traffic systems can track multiple threats, and they are often linked to graphical terrain and weather displays that greatly enhance pilot situational awareness.

When flying in visual or instrument conditions, pilots get a “God’s-eye” view of the traffic, weather, and terrain around them, and the big picture allows them to make informed safety decisions. When traffic does appear, the systems usually provide aural callouts that include distance and azimuth (“Traffic, 10 o’clock, less than one mile!”) so that pilots can keep their eyes outside at critical times.

A drawback of TIS-based systems is their tendency to call out your own airplane’s radar return as a traffic threat when performing steep turns or other maneuvers. After many false alarms, it’s easy for pilots to become complacent about the dubious warnings.

The main TIS shortcoming, however, is that it’s only available in terminal areas covered by the FAA’s network of 129 ASR-7, -8, and -9 radar sites—and those sites are slated to disappear, eventually. Much to the dismay of AOPA and more than 10,000 pilots and aircraft owners who have purchased Mode S transponders and traffic warning systems that rely on TIS technology, the FAA announced in 2005 that it intends to slowly abandon TIS as it transitions to a new style of radar (ASR-11) that doesn’t pass along traffic information to pilots. At least 22 of the FAA radar sites that once supported the TIS network have been dropped, or are targeted for replacement. TIS works well, however, over the mostly high-density population centers where it currently exists. Eventually TIS will give way to its more technologically advanced NextGen cousin, TIS-B (the B is for broadcast). TIS-B is a feature of the ADS-B “in” system, and it is expected to offer traffic warning information over a much larger geographic area than the current TIS. But the new system’s retail prices are unknown, and it will only show aircraft that provide ADS-B “out” signals, and those signals won’t be mandated until 2020. At that time, the FAA says it will require GA aircraft to carry both radar transponders and ADS-B transmitters, so TIS likely has at least a decade of useful life remaining.

Active systems

Unlike passive traffic systems, active units send out their own signals and interrogate other transponder-equipped aircraft within range. Such active systems are more expensive and, until the past few years, were only found in business jets and high-flying turbine aircraft. Their main advantage is that they work independent of ground-based radar and TIS broadcasts, and they still perform in areas where radar coverage is spotty or nonexistent. But as with other traffic systems, aircraft that fail to provide transponder or ADS-B out signals aren’t displayed.

The growing popularity of aerial traffic warning systems and their safety benefits have convinced avionics manufacturers to develop products that incorporate the best of existing systems, and comply with rules that will govern ADS-B in the future. Avidyne, Garmin, and L-3 Avionics, for example, have developed full product lines for piston and turbine airplanes as well as helicopters that can synthesize information from ground-based radar, other transponder-equipped aircraft, and ADS-B to provide an easy-to-understand traffic picture of surrounding aircraft.

The growing popularity of aerial traffic warning systems and their safety benefits have convinced avionics manufacturers to develop products that incorporate the best of existing systems, and comply with rules that will govern ADS-B in the future. Avidyne, Garmin, and L-3 Avionics, for example, have developed full product lines for piston and turbine airplanes as well as helicopters that can synthesize information from ground-based radar, other transponder-equipped aircraft, and ADS-B to provide an easy-to-understand traffic picture of surrounding aircraft.

Avidyne purchased traffic and weather system innovator Ryan International in 2005 to help develop these technologies; Garmin was the first to offer units made to comply with evolving NextGen specifications, and L-3 has modified its pioneering SkyWatch system to cover a broad spectrum of GA aircraft.

Avidyne’s TAS600 series, Garmin’s GTS 800 series, and L-3’s SkyWatch are designed to reliably show traffic now, during the ADS-B transition, and well into the future. These products range widely in price, power, and capability and are meant for GA aircraft from piston singles to helicopters and business jets.

Some active systems require two antennas per aircraft to see both traffic above and below, and they’re larger, more complex, and more costly than passive systems. Avidyne’s 600 series starts at about $8,500 for single-engine piston airplanes that fly below 18,500 feet, and the company is offering ADS-B upgrades for an additional $2,000 per unit. Avidyne’s traffic products expand in capability and cost up to $21,000 for fast-moving jets that fly all the way up to 55,000 feet. Garmin’s GTS 800 products range in price from about $10,000 to $24,000, and they offer a similar range of features and capabilities as well as NextGen compatibility.

Impressive benefits

Given the relative rarity of midair collisions (about one a month in the United States, and 48 reported near-misses), it may seem surprising that traffic warning systems are becoming regarded as essential equipment. But most pilots have been surprised at some time or another to find another aircraft flying closer than they expected. And it seems that ATC is constantly alerting us to other airplanes that we just don’t see, even when they’re flying close by, in good weather, and we know where to look for them.

A study of collision avoidance systems determined that pilots flying in clear weather visually identify other aircraft 86 percent of the time when a traffic system (or ATC) points out its relative position. Pilots’ ability to spot traffic falls to 56 percent without distance and azimuth callouts. Once pilots realize how much traffic is out there that they don’t see, they quickly come to rely on electronic tools meant to help keep them apart.

A study of collision avoidance systems determined that pilots flying in clear weather visually identify other aircraft 86 percent of the time when a traffic system (or ATC) points out its relative position. Pilots’ ability to spot traffic falls to 56 percent without distance and azimuth callouts. Once pilots realize how much traffic is out there that they don’t see, they quickly come to rely on electronic tools meant to help keep them apart.

Traffic warnings are a major attribute of the NextGen system—and there’s little doubt that a satellite-based network can provide better coverage, especially in remote locations, than radar does now. But as more pilots see for themselves the benefits of the traffic systems available today, they realize that even imperfect systems offer impressive benefits.

“Pilots who have flown with traffic systems come to trust them and don’t want to fly without them,” said Tom Harper, marketing director for Avidyne, which has sold more than 10,000 traffic avoidance systems for GA aircraft. “They quickly become believers. They want that extra set of electronic eyes looking out for them.”

E-mail the author at [email protected].