Curious cargoes

When airplanes were the only option

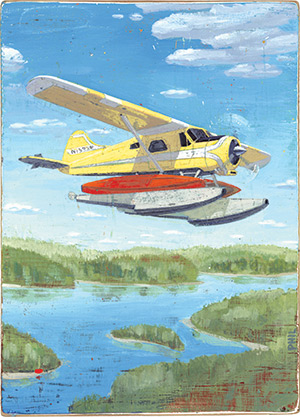

Illustration by Phil

We were flying along enjoying the beautiful northern Maine scenery passing underneath our pontoons, when one of the passengers in the rear leaned forward—and bit me on the arm. Just one more hazard in a bush flyer’s life.

We were flying along enjoying the beautiful northern Maine scenery passing underneath our pontoons, when one of the passengers in the rear leaned forward—and bit me on the arm. Just one more hazard in a bush flyer’s life.

These “passengers” were anything but normal: They were Canada geese. We were giving geese, creatures noted for their quintessential flying ability, a ride in a de Havilland Beaver seaplane. That ain’t all, folks. As Alice in Wonderland said, “It gets curiouser and curiouser.” This was an attempt to turn tame “city” geese back into creatures of the wild.

Anyone who lives in or near the large urban centers—particularly in the Northeast, places such as southern Connecticut, Long Island, Philadelphia, et cetera—knows that geese can be a nuisance around golf courses, parks, beaches, lawns, even airports, where they feed on the grasses and leave their droppings everywhere. This phenomenon is relatively recent. Once upon a time, before well-intentioned but misguided people messed up their lives by feeding and getting them hooked on handouts, Canada geese were totally migratory, spending their summers nesting in the far north. But geese are easily addicted to handouts, and hundreds of thousands of them are now many generations removed from their migratory ancestors.

A team from the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, led by Wildlife Biologist Pat Corr, spent a few weeks for several summers capturing some of the geese. By taking advantage of the birds’ molting time in late June when adults shed their flight feathers and are unable to fly, and chicks haven’t yet fledged, they were able to herd and corral hundreds of geese and truck them back to Maine. The birds were then distributed and released in many remote locations in hopes of establishing populations.

Most of the geese, contained in chicken crates, were trucked to release sites when possible. But some were flown to remote lakes and ponds.

The backseat of the Beaver had been removed and the rear compartment carefully lined with plastic sheeting for easy cleanup after these messy birds. Crates filled with geese and their chicks were stacked from floor to ceiling. At the destination the crates were taken out on the pontoon, opened, and the birds released in their new homes. The biologists were well aware and expected that the adults would eventually fly back to their city neighborhoods. But the strategy was that chicks, having imprinted upon this new location, would now consider this “home” and return in future springs to raise their own young.

Did it work? Anyone who has flown into Greenville on Moosehead Lake, or attended the annual International Seaplane Fly-in there—and seen the several hundred geese flying in and out in formation—has seen part of the result. Similar sights are now found in many parts of the state. Some people, whose lawns and beaches have been befouled, think it has worked too well.

The next cargo

Bush flying is seldom routine or boring. A pilot never knows, from day to day, what his next flight or cargo will be. This was especially true in the 1950s and early 1960s when I was involved, flying for Folsom’s Air Service in Greenville, Maine. Unlike today, roads in the backcountry were rare. Most everything people consider essential to living in remote areas had to be flown in. The airplane became the taxi and the light truck. And pilots continued to find innovative, ingenious, and sometimes risky ways to use their craft and skills.

Federal aviation inspectors might have been aghast had they been around to see how some pilots used their airplanes then. It wasn’t at all unusual to see any manner of material tied or strapped to pontoons, or jammed into cockpits, with seemingly little regard for gross weight limits, or aerodynamic effects on already “dirty” and low-powered aircraft. But these guys figured they had the experience and know-how to pull it off, and usually did. But not always.

One pilot left Greenville with a load of lumber, including sheets of plywood, tied to the struts of his Cessna 180, en route to a cabin-building site. He never made it. The ties holding the front of the lumber load let go. The front of the wood slammed up against the belly of the airplane. This created huge aerodynamic drag. Unable to maintain altitude, the pilot, using consummate skill, managed to bring the airplane down in a “controlled crash” in a bog. He was unhurt. His airplane sustained only slight damage and was recovered by helicopter.

Andy Stinson (now 84 years old and still rebuilding and actively flying airplanes after 60 years of flying) is the only other surviving member of Dick Folsom’s operation from the 1950s. He recalls flying many times with unusual cargoes, but the touchiest one involved crates of dynamite in the rear compartment—and the blasting caps in his pants pocket.

Flying for Folsom’s was never dull, always busy. On a given day I might fly a load of guests into or out of some remote sporting camp such as Nugent’s Wilderness Camps on Chamberlain Lake, or Rainbow Lake Lodge; or to a place where they would tent out, like Lobster or Allagash lakes (see “ Arctic Lodges”). I might have to fly a truck part to a lumber camp, a mechanic to a river-driving towboat, or a technician to service someone’s gas-powered refrigerator. Often, it was supplies that filled the backseat to be flown in to someone’s remote camp.

One of the cargoes I dreaded was flying gasoline. The rear seats would be removed, and the entire compartment filled with as many five-gallon cans of gas as it would hold—making sure that all covers were secure and none leaked. I always took pains to fly the airplane as gently as possible and not jiggle those cans to set off a spark. A gasoline fire in that fabric airplane would incinerate it—and me—in seconds. The gasoline was delivered to remote camps, which needed it to fuel outboard motors, chain saws, generators, and such.

There was a story circulated of a pilot (not from Folsom’s but from another company, Holt’s) who was just taking off with a load of gasoline cans when he discovered a fire starting around the nozzle of one of the cans. This he became aware of just as his airplane attained flying speed and lifted from the water. Expecting the whole cargo to erupt any second, the pilot pushed open the door, figuring to jump out and take his chances in the water, rather than in a fire. Just as he opened the door, a blast of air entered the cockpit and snuffed out the flame. The grateful pilot reached back, screwed down that loose cap, and continued on his flight. He obviously was one cool—and miraculously lucky—cat.

Backcountry inhabitants

By eastern United States standards, Maine is still a relatively wild place. With some 17 million acres—roughly 20,000 square miles—in unorganized, forested wild lands, it’s the largest such chunk of undeveloped land east of the Mississippi. Relatively uninhabited, this large area in some ways is still a small town in that everyone knows personally or by reputation just about everyone else who lives in the backcountry.

This is especially true of pilots, who get around and are likely to have more dealings with the backcountry inhabitants—trappers, guides, camp operators, or hermits. When I was working that country there were a number of such recluses who chose to live alone in the backwoods, making a meager living by trapping, guiding, or picking up an odd job with a logging or river driving company. Most, when I knew them, were older men; it was thought many were veterans of World War I. All were characters.

My old friend Andy Stinson (what a great name for an old-time bush pilot!), during his many years of backcountry flying, got to know most of the characters scattered around the woods. One of Andy’s regular flights was to haul the mail to Chesuncook Village, a tiny community near the north end of Chesuncook (called ’Suncook by the locals) Lake. It could be reached only over 20 miles of water (or ice in winter).

Andy was flying an airplane on skis on a cold winter day when he spotted a hermit who lived alone across the lake from the village. (Even that tiny village, with its winter population of fewer than 10 souls, was evidently too crowded

for him.)

The man, Hiram Johnson, had been out to town to pick up a load of supplies and was headed back to his isolated cabin, on snowshoes, towing his load on a handsled (called a moose sled in local parlance). He had walked several miles, but still had at least 10 more miles to go.

On an impulse, Andy circled around, landed on the lake alongside Hiram, and offered him a ride. The old man, a bit skeptical, wondered how they could bring his sled. After convincing Hiram to climb aboard, Andy loaded the supplies in the airplane and tied the snowshoes and sled to the airplane’s jury strut. The flight to Hiram’s cabin was uneventful. “Probably the only time anyone ever gave him a lift,” Andy says.

Tying stuff onto struts and floats was fairly routine in those days. Canoes were commonly hauled tied to the float struts, as were lumber, long pipes, sheet metal, et cetera. In hunting season, deer were frequently hauled out strapped to the floats, as well as an occasional bear.

Flying a Seabee

For several years in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Ray O’Donnell operated a flying service in Greenville, located in the buildings now occupied by the Maine Forest Service. O’Donnell’s fleet when I knew him was comprised of an Aeronca Champ and a Republic Seabee. The Seabee, a classic amphibian flying boat, he quite literally used as a truck. O’Donnell had removed the heavy landing gear to allow a greater payload.

I must admit I was a bit skeptical about the Seabee. It didn’t look like it should fly well, with that big, blunt cabin; pusher propeller; and skinny aft fuselage. Some pilots I knew dismissed it as having the glide ratio of a brick. As a neophyte, these comments made an impression on me. The one time I flew in O’Donnell’s Seabee it left me impressed with its ability to haul freight.

O’Donnell flew up to Nugent’s on Chamberlain to fly me and the hunter I’d been guiding back to Greenville. This “sport” of mine had brought a mountain of clothing and survival gear for his week’s stay. We had piled this all on the dock, along with the eight-point 180-pound buck he’d shot. I figured O’Donnell would need two flights to take it all out. In my estimation the Seabee had one flaw: Its huge, comfortable cabin was just too big. It was just too tempting to keep piling stuff in there. We kept loading that gear until the Seabee had swallowed it all. Then we put the big buck on top of the pile, and all climbed aboard.

The takeoff for me was white-knuckle time. Naturally, the lake that day was almost flat calm—no assist from wind to provide lift. Fortunately, Chamberlain Lake is some 20 miles long, so we had plenty of runway. It seemed to take forever for the big, lumbering Seabee to get on step, and then an interminably long run up the lake before the airplane finally, reluctantly, lifted off. (I later found out O’Donnell didn’t believe in using flaps on takeoff.)

The return flight to Greenville was uneventful, although our climbout seemed painfully slow. By the time we reached Greenville, 60 miles away, we were only some 800 feet agl. I was a bit surprised, as we approached East Cove, that O’Donnell didn’t set up a gradual, straight-in approach as was the norm. Instead he held the altitude until we were directly over Mile Light, which marks the north end of the cove. I figured he was going to circle to set up a landing approach. Instead, with only a mile of water left beneath us, O’Donnell eased the throttle back what seemed a minute amount. The Seabee slid down out of the sky as if on an elevator. In seconds he was flaring—and on the water in as neat a landing as you could ever hope to see.

Thanks to the thousands of miles of roadways built by the major landowners in the 1970s, when it became cheaper to haul wood by trucks than sending it down rivers, the need for much of the aerial bush hauling has been pretty much eliminated. Today it’s generally possible to haul freight by truck—or combination truck/boat—to most places in Maine’s north country. Seldom today will you see a refrigerator or load of lumber ferried by airplane. One of the busiest flying services in the area, Jack Currier’s at Greenville Junction, now relies solely on tourism and scenic flights. He and his pilots never have to load near or over gross; they take off and land in familiar locations, and tourists likely wouldn’t take kindly to being strapped to the pontoons. (Closest I ever saw: legendary bush pilot Charlie Coe flying Folsom’s Beaver with a guy sitting in the float compartments on each side with their heads sticking out, as a stunt at the International Seaplane Fly-In.)

Some few oldsters might experience a twinge of nostalgia for those days of virtually unrestricted aerial derring-do, but the FAA, at least, must relish the new, saner attitude in the northern skies.

Paul J. Fournier, AOPA 5799247, of Palm Bay, Florida, is a commercial pilot with more than 2,000 hoursof flying time. He spends his summers in Maine.