Dogfight: Pattern Entry

"Any way you want?" vs. "A pox on 45-degree pattern entries"

Editor at Large Tom Horne and Senior Editor Dave Hirschman have a lot of things in common: lots of ratings, lots of experience in lots of airplane models—and lots of opinions (and similar haircuts). We last turned them loose on the topic of crosswind landings (see “ Landing Insights,” August 2010 AOPA Pilot) and the response to two different schools of thought on a topic garnered some of our most interesting musings from a large number of readers. So with “Dogfight” premiering this month, we hope you’ll enjoy these two takes on a topic—and let us know what you think, too. —Ed.

Any way you want?

A plea for pattern sanity

By Thomas A. Horne >

By Thomas A. Horne >

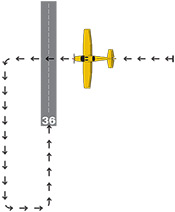

Flight instructors teach standard, 45-degree-entry traffic patterns for a number of good reasons—all of them based on safety considerations. At nontowered airports, the idea is to enter the downwind leg of a traffic pattern at midfield, flying a heading that’s 45 degrees to the runway centerline. This gives you an excellent vantage point from which to observe any other traffic in the immediate area.

From this perch you can see all arriving and departing traffic, plus any airplanes taxiing. You can even see any rogue pilot attempting to “split” the runway by flying overhead the airport and directly turning downwind—and potentially cutting off any traffic that is already established in the pattern.

It’s all about telling everyone where you are—something quite valuable in a nontowered setting.

Standard pattern practice is advisable for another reason. It gives pilots standardized checkpoints for making power and configuration changes—and making predictable radio calls. For example, you’d want to announce your position relative to the airport when, say, five or 10 miles out so as to give anybody in the pattern an idea that you’re on the way—and to keep a lookout. Same thing with calls on downwind, base, and final. It’s all about telling everyone where you are—something quite valuable in a nontowered setting.

Here’s something else: It’s what other pilots are expecting you to do. The vast majority of pilots are not expecting someone coming from the other side of the runway, and flying without the bother of announcing their position or intentions.

Sure, pilots flying standard patterns have plenty of lapses in their technique. Some fly too wide a pattern—the so-called “B–52” pattern. Some extend their downwind legs too far, which invites those behind them to turn base and final ahead of them. Some simply ignore standard pattern procedure and make straight-in approaches to the runway, or dispense with the downwind leg altogether and make an abrupt “base to final” radio call to speed their arrival over the numbers.

Sure, pilots flying standard patterns have plenty of lapses in their technique. Some fly too wide a pattern—the so-called “B–52” pattern. Some extend their downwind legs too far, which invites those behind them to turn base and final ahead of them. Some simply ignore standard pattern procedure and make straight-in approaches to the runway, or dispense with the downwind leg altogether and make an abrupt “base to final” radio call to speed their arrival over the numbers.

All of these common shortcomings, it must be said, also allow those making midfield entries to cut off, or descend into, those flying down final. Those who have the right of way.

Yes, you can fly a VFR pattern any way you want at a nontowered field. But barging into a busy airport by flying a nonstandard pattern isn’t the best of ideas.

E-mail the author at [email protected].

A pox on 45-degree pattern entries

Save time, avoid conflicts, eliminate chatter

< By Dave Hirschman

< By Dave Hirschman

When approaching nontowered airports to land, pilots ought to fly in a predictable, visible way that minimizes traffic conflicts and gets them safely on the runway in as little time as possible.

Sometimes, a 45-degree entry onto the downwind is the most expeditious method. Sometimes it’s not. When it’s not, abandoning the 45-degree entry is in everyone’s best interest—even the self-appointed pattern sheriffs who get so unhinged about such things.

The reason for an abbreviated pattern isn’t that the pilots who perform them are in a hurry, short of gas, or rude. Instead, getting on the ground quickly minimizes potential midair conflicts—and those unhappy encounters are largely a function of the time multiple aircraft are buzzing around together in the same airspace.

Sometimes abandoning the 45-degree entry is in everyone’s best interest.

At my as-yet-nontowered home airport on Saturday afternoon, I sat in a lawn chair with a radio transceiver and observed a variety of pattern entries. First, a flight-school Cessna 172 crossed overhead at 2,500 feet agl heading east. In accordance with their habits and customs, the student pilot and instructor proceeded straight ahead for several miles, descended, maneuvered for a 45-degree pattern entry, flew a precise rectangular pattern, and landed on the southwest-facing runway.

Total elapsed time from crossing overhead the airport to touchdown was nine minutes 40 seconds and included eight radio transmissions (overhead the airport; maneuvering for the 45; entering the 45; on the 45; entering the downwind; mid-field downwind; base, and final). Soon after, a Bonanza arrived from the same direction, crossed overhead the airport at 1,000 feet agl, turned downwind, and landed. Total elapsed time from crossing overhead the airport to touchdown was one minute 50 seconds, and the pilot’s thumb depressed the transmit button just four times (midfield crosswind; downwind; base, and final).

The Bonanza pilot’s pattern entry procedure is time-honored, FAA-approved, and—most important—commonsensical. By arriving in a predictable location and shortening the amount of time spent maneuvering in busy airspace at low altitude, the Bonanza pilot was considerate to fellow fliers and noise-sensitive airport-area residents alike.

The Bonanza pilot’s pattern entry procedure is time-honored, FAA-approved, and—most important—commonsensical. By arriving in a predictable location and shortening the amount of time spent maneuvering in busy airspace at low altitude, the Bonanza pilot was considerate to fellow fliers and noise-sensitive airport-area residents alike.

The student and instructor in the 172, while conscientiously adhering to the FAA’s 45-degree pattern entry guidance, subjected themselves and fellow pilots to greater risk of midair conflicts and tied up an already busy CTAF with radio chatter.

When approaching nontowered airports from the “cold” side, a midfield crosswind is the most desirable pattern entry. A standard crosswind is second best, and flying upwind and then maneuvering for the 45 is a last resort.

E-mail the author at [email protected].