Technique: The 'Panic Pull'

Out of your comfort zone? Don't yank on the yoke

Attitude isn't everything

I was practicing for an aerobatic contest in an underpowered biplane, and my loops were consistently and frustratingly egg-shaped.

To make them round, I'd have to tighten them, and that meant pulling sooner and harder on each maneuver. From level flight I'd pull about four Gs until the nose was vertical, relax the back-pressure as the airplane floated over the top, then pull four Gs again as quickly as possible while the nose fell and airspeed increased.

That's when I got an eye-opening, real-world lesson about angle of attack.

With the nose of the biplane pointed straight down and pulling aggressively on the stick to minimize the radius of the loop, buffeting airflow over the wings made it feel as if I was driving down a bumpy country road. Determined to make the loop round, however, I kept pulling until, finally, the airflow separated, the wings stalled, and the airplane snapped 90 degrees to the right.

The instant I relaxed the back-pressure, the airflow reattached and I emerged from the botched maneuver.

I had heard and read during private pilot training that a wing could stall at "any airspeed and any attitude." But it hadn't occurred to me that an airplane pointed straight down at full power could exceed its critical AOA and stall. Finally, the light came on and I was able to grasp a concept that I had never fully understood or appreciated: An airplane's attitude and its AOA really are completely unrelated.

An F–22 Raptor can climb vertically and accelerate straight up at a very low AOA, while an Extra 300 can snap roll with its nose pointed at the ground and a very high AOA.

Since then, I've provided more than 1,000 hours of dual aerobatic instruction, and observed many fellow pilots deepen their understanding of AOA—usually by way of a seemingly endless variety of hopelessly screwed-up maneuvers. But that's how pilots learn, and for most of us, it takes real-world events for theoretical concepts to jell.

Of course, you don't need unusual-attitude training to understand AOA. Just realize that, in normal flight, pulling on the stick or yoke increases AOA—and when you reach the critical angle, the way to recover is to reduce the AOA regardless of the airplane's attitude.

In most of life, attitude is everything. With AOA, however, attitude means nothing. —DH

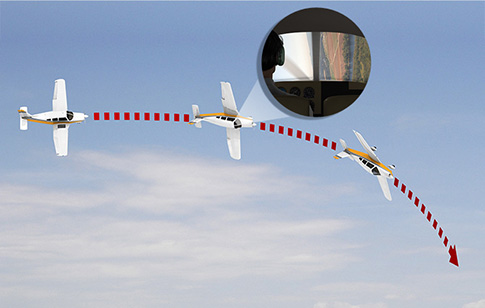

The main goal of unusual-attitude training is breaking the deeply ingrained and nearly universal “panic pull” reflex that causes pilots to haul back on the stick or yoke when bank angles exceed their comfort levels.

A multiyear study by Aviation Performance Solutions LLC (APS), an Arizona firm that offers a range of upset recovery courses, found that the pull reflex is especially strong—and particularly perilous—at low altitudes, and it afflicts new pilots as well as seasoned pros.

“An alarming 90 percent of pilots without previous upset recovery experience ‘pull’ when faced with an overbank situation beyond 90 degrees,” according to an APS report. “A full nine out of 10 pilots, regardless of experience level, will most likely pull into the ground in a wake-turbulence upset or cross-controlled stall when faced with the situation for the first time.”

The reason for the reflex is easy to understand. From the very beginning of general aviation flight training, pilots learn to equate pulling on the stick/yoke with climbing—and for almost all of our time aloft, that remains true. Most GA pilots seldom venture beyond 60 degrees of bank or 30 degrees of pitch. And although corporate and airline pilots can be expected to log tens of thousands of flight hours during their careers, they strive to keep their aircraft within even narrower limits.

Simulator training has proven tremendously effective at realistically re-creating a wide variety of scenarios, especially in-flight emergencies. But even full-motion simulators can’t faithfully reproduce the strenuous and sometimes disorienting sensations of flying through the full 360 degrees of pitch and roll, accelerated stalls, and spins. Only flying through the full spectrum of flight attitudes, airspeeds, and angles of attack can do that.

The NTSB recommends that air carriers and commercial operators “provide their flight crews with training in the recognition of the recovery from unusual attitudes and aircraft upsets.” Eclipse Aviation went so far as to make unusual-attitude training a requirement for completion of the EA500 type-rating course.

A variety of U.S. flight schools currently offer unusual-attitude training in Aerobatic-category aircraft ranging from vintage clipped-wing Piper Cubs to unlimited Extras and warbirds such as the North American AT–6 and the L–39 jet. Some of the courses are designed to appeal to individual GA pilots, and others are tailored to corporate flight departments or ab initio airline training programs. All of them concentrate on overcoming the deeply ingrained pull reflex.

“All of their instincts tell them to pull, and that reaction is very strong and almost universal,” said Lee Lauderback, founder of Stallion 51, a Florida firm that conducts unusual-attitude training in a dual-control P–51 Mustang and is preparing to launch a separate company, UAT, for unusual-attitude training for corporate pilots using an L–39 jet. “To be effective, the training has to take place in an airplane that’s similar in performance to the airplanes the pilots fly on a regular basis—and strong enough that they won’t pull the wings off it.”

“All of their instincts tell them to pull, and that reaction is very strong and almost universal,” said Lee Lauderback, founder of Stallion 51, a Florida firm that conducts unusual-attitude training in a dual-control P–51 Mustang and is preparing to launch a separate company, UAT, for unusual-attitude training for corporate pilots using an L–39 jet. “To be effective, the training has to take place in an airplane that’s similar in performance to the airplanes the pilots fly on a regular basis—and strong enough that they won’t pull the wings off it.”

When pilots undergoing unusual-attitude training make mistakes, such as pulling on the stick/yoke at bank angles beyond 90 degrees, Aerobatic-capable airplanes such as the P–51 or L–39 flying at safe altitudes allow pilots to experience the consequences, Lauderback said. “It makes a lasting impression when they lose 8,000 feet and pull out of a botched maneuver at 350 knots,” Lauderback said. “That’s a teachable moment, and in the future they’ll be a lot less likely to make the same mistake again.”

Rich Stowell, a Master CFI of aerobatics who teaches in Santa Paula, California, and wrote the book Emergency Maneuver Training, takes students through the full range of in-flight upsets in a Pitts S–2B or 8KCAB Super Decathlon, but also emphasizes prevention.

“Unusual-attitude recovery is conceptually simple,” Stowell said. “It’s either a spin recovery or a roll recovery. But the key is to recognize and avoid situations that can lead to one of these two unusual attitudes in the first place. Prevention is always preferable to cure, especially when most stall/spins—as well as wake turbulence encounters—occur close to the ground.”

Stowell developed the PARE spin recovery method (Power idle; Ailerons neutral; Rudder opposite rotation; and Elevator forward). For spiral or overbanked recoveries, he teaches Power (nose up/power up; nose down/power down); Push (reduces the angle of attack and checks the panic pull); and Roll (using coordinated aileron and rudder).

APS also uses the PARE technique for spin recoveries but offers its own mantra (Push, Power, Rudder, Roll, Climb) for rolling upsets. Push reduces the angle of attack; Power corrects airspeed; Rudder (neutral); Roll (wings level), and Climb.

“Primary training only addresses slightly more than 11 percent of the all-attitude environment,” said Paul “B.J.” Ransbury, a former Canadian military pilot and APS founder, whose company uses Extra 300L aircraft for unusual-attitude training. “The easiest part of upset training is imparting the motor skills. The most challenging aspect is developing a pilot’s mental discipline to apply counterintuitive strategies in a time-critical situation that’s likely to be life threatening.”

In addition to these techniques, those who provide unusual-attitude training have developed some of their own common-sense procedures.

Joey “Gordo” Sanders, an air racer and former U.S. Air Force fighter pilot (www.sandersaviation.com), urges pilots to use their sense of hearing for strong hints about the airplane’s attitude. Increasing wind noise—and rpm, in airplanes with fixed-pitch props—is a good hint that the nose is down and airspeed is increasing, he said.

“Lots of our senses can be tricked while flying,” Sanders said. “But pilots can learn a lot simply by listening to what’s going on around them.”

Bill Finagin, a veteran aerobatic performer and instructor in Annapolis, Maryland (Dent Air Ltd.), teaches pilots a method reminiscent of the Hippocratic Oath’s admonition to “do no harm.” Finagin starts by immediately and affirmatively neutralizing the controls, so at least the pilot isn’t aggravating the situation while trying to solve it.

Flight schools that specialize in unusual-attitude training say that it takes multiple flights for the methods they teach to take hold. APS, for example, found that four or five training flights of one hour (or less) each over three days produced the best results.

Stowell recommends about the same number, with a maximum of two unusual-attitude flights a day.

Exposure to extreme pitch and bank angles allows pilots to eliminate the panic response. Familiarity with the sights, sounds, and sensations of unusual attitudes aids in their recognition. Once pilots recognize the flight condition, finding the shortest way to bring the airplane back to normal flight is a relatively straightforward matter.

Once the panic pull is successfully suppressed, APS and other schools recommend that pilots keep their new habits sharp through regular practice, or an annual refresher course at a minimum.

Email the author at [email protected].