Strange and unusual crashes

Any landing you can walk away from...

You probably didn’t hear anything about this—I only learned of it because I lived maybe two miles from the crash site—but if you want to look it up there might be an accident report on the Internet somewhere. Or Google it for more details. Anyway, here’s the story: In January 2009 an airliner, I think a US Airways Airbus A320 or something, took off from LaGuardia International Airport in New York and almost immediately sucked a flock of birds into its two engines. They choked and died, and the pilot, whose name was Chesley Sullenberger (imagine the teasing that poor guy must have taken in school!), performed a 180 and executed a smooth landing in the Hudson River.

The airliner eventually sank and was a total loss, and all the passengers lost their luggage and probably their coats, and everyone had to huddle on the wings in the freezing cold while ferries loaded them up and hauled them ashore. Nonetheless, it was a decent landing, all things considered, and everyone walked away from it—even a flight attendant who broke a leg and a guy who jumped in the water. Oh, you heard about it?

Thus it proved the adage, “Any landing you can walk away from is a good one.”

Wrestling a Warrior

Any pilot with more than 500 hours has logged one of those. Mine happened in the late 1990s, after I promised my friend Peter that I’d take him and his new girlfriend up for a flightseeing tour down and up the very same Hudson River. They were both really eager to do it, and on the appointed day—actually the same date that Sullenberger ditched a decade later—they picked me up in her car and drove us to Lincoln Park, New Jersey. Conditions weren’t right, though. It was crystal clear, but with a strong, gusty wind. No one at Lincoln Park was flying, and every molecule in my body told me to cancel.

The 182 slammed into a fence and flipped over—into a lot packed with portable toilets.

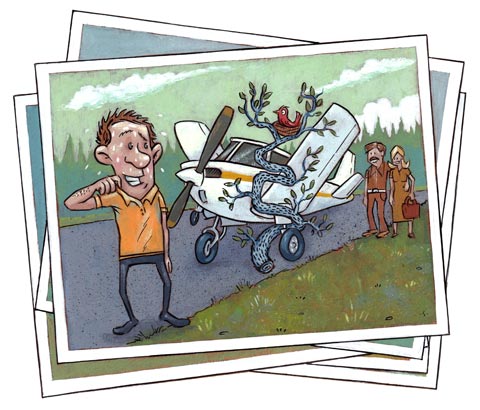

So, naturally, we crawled inside an almost-new Piper Warrior and took off, flying low and fighting clear-air turbulence all the way to the George Washington Bridge, circling the Statue of Liberty, and back to the bridge and then to Lincoln Park. No doubt as a result of my exemplary piloting skill, neither of them noticed how much of a struggle the Warrior was throwing at me. On final I lined up on the runway, which is narrow and has a displaced threshold because of the 75-foot-tall trees lining the south end. Creeping in, fighting the wind, with full flaps, we were halfway clear of the trees and at the proper altitude. Then the wind…just died. The Piper dropped, and I could hear the gear ripping branches off the treetops. Peter and his woman heard it, too.

We all heard the branches scraping the runway when the gear hit the ground and while I taxied back to the FBO. We pulled up to the tie-down spot, and while I tied the airplane down, I checked for damage and pulled branches from the main gear. They wanted to take photos. In the photos, they look smiling and happy, and I look nervous and sweaty, like I’d just hit some trees or something. Later, she told Peter, “Promise me you’ll never fly with him again.” He mentioned that to me that a few years afterward, following their breakup.

I also told a flight instructor about it.

“What the hell were you doing, flying with full flaps in turbulence like that?” he said, loudly.

Finding humor

Although it certainly stuck in my brain, admittedly the incident wasn’t all that exciting, not when compared to what happened to another pilot recently. He took off from Thun Field, which lies southeast of Tacoma, Washington, in a Cessna 182. At an altitude of about 150 feet the Cessna’s engine died, and the pilot did his level best to swing back around and land on the runway. That low, he couldn’t make it. The 182 slammed into a fence and flipped over—into a lot packed with portable toilets. They cushioned the impact, and the pilot was able to crawl out and walk away. And lucky for him—if anything about crashing your airplane can be considered lucky—all the toilets were empty.

Although it certainly stuck in my brain, admittedly the incident wasn’t all that exciting, not when compared to what happened to another pilot recently. He took off from Thun Field, which lies southeast of Tacoma, Washington, in a Cessna 182. At an altitude of about 150 feet the Cessna’s engine died, and the pilot did his level best to swing back around and land on the runway. That low, he couldn’t make it. The 182 slammed into a fence and flipped over—into a lot packed with portable toilets. They cushioned the impact, and the pilot was able to crawl out and walk away. And lucky for him—if anything about crashing your airplane can be considered lucky—all the toilets were empty.

Yet that story pales in comparison to the case of die-hard Green Bay Packers fan, freelance photographer, and pilot Frank Emmert. It’s a tradition for Packer fans to wear wedge-shaped cheese hats to Packers games; only the hats are made from foam, not cheese. Non-cheesehead-hat-wearing fans complain that they block their view of the game, and have called for banning hats. Not Emmert, even if they blocked his view. In 1995, following a game with the Cleveland Browns, Emmert was flying right seat in a single-engine Cessna with fellow fan Baron Bryan at the controls.

After that, Emmert wouldn’t part with it. “I’ll even put it on my checklist. ‘Cheese—check.’”

The Cessna began picking up ice and sinking. Bryan tried to make it to the nearest airport, Stevens Point Municipal, but the airplane couldn’t. Emmert, who had his cheesehead hat on his lap—he’d been napping and used it as a pillow—put it on just before the airplane went in. So here’s an airplane about to crash, and one of the pilots is wearing a cheesehead hat. While the cheesehead-hatless Bryan suffered facial lacerations, Emmert’s cheesehead hat hit the panel and cushioned his head. He hurt his ankle and couldn’t exactly walk away, but the cheesehead hat did prevent him from suffering major injuries.

After that, Emmert wouldn’t part with it. “I cleaned it up, so it’s not that bad,” he later explained. “I’ll even put it in my checklist. ‘Cheese—check.’” He ended up doing a nationally broadcast spot for the NFL, and appeared on The Tonight Show riding a motorized cheesehead cart. Ironically, three months before the crash, he had been hired to take publicity shots for Foamation, a company that makes cheesehead hats.

Not so funny

Sometimes the only road ahead happens to be a body of water. A former colleague, Amy Laboda, says she saw a Cessna 206 at Air & Sea Recovery, based on Florida’s Gulf Coast, that the pilot had ditched near the shore. It skidded to a halt on a sandbar about two feet below the surface, as the pilot intended. Otherwise, it was a perfect landing; he didn’t even get wet. But the airplane sat there six weeks before the recovery guys could take it out by barge, and by that time it was beyond help.

Laboda, by the way, was at the salvage lot to see the remains of her Cessna 210 that Air & Sea Recovery had just fished from the ocean.

It was in 2001, and she and four others—her two young kids, their babysitter, and a passenger along for the ride—departed Key West on a hot, muggy, essentially lift-free day. It took the 210 three minutes to reach 1,500 feet. Then the engine popped and died. Laboda says she had enough time to call mayday and hear the tower say she could land on any available runway, but not enough time to respond or run through the emergency checklist. Nauseatingly thorough, though, Laboda had made sure to brief everyone on what to do in case of an unscheduled water landing, like how to unlatch the doors (even forcing them try it a few times), how to pull the life raft out of its place between the seats, how to inflate the life vests (which she insisted everyone wear during the flight—and which the kids complained furiously about before takeoff), and to follow air bubbles (which always head to the surface). Hell, she even made sure both kids knew how to swim.

Ninety seconds after the engine died, the airplane hit the water belly first, followed by the tail, which slowed the Cessna down. A textbook ditching, but you’d expect no less from Laboda. The ocean popped out the windscreen, and Laboda went out through it. Once she surfaced, maternal instinct kicked in and she started looking for the kids. They were already out, along with the babysitter and the other passenger. The life raft wasn’t, though, and the 210 disappeared below the surface in one minute. But within five minutes search and rescue pulled up with a boat and hauled them in and back to shore. In this instance, any landing you can swim away from is a good one.

Ninety seconds after the engine died, the airplane hit the water belly first, followed by the tail, which slowed the Cessna down. A textbook ditching, but you’d expect no less from Laboda. The ocean popped out the windscreen, and Laboda went out through it. Once she surfaced, maternal instinct kicked in and she started looking for the kids. They were already out, along with the babysitter and the other passenger. The life raft wasn’t, though, and the 210 disappeared below the surface in one minute. But within five minutes search and rescue pulled up with a boat and hauled them in and back to shore. In this instance, any landing you can swim away from is a good one.

Test pilot

One final tale. Back when there were but three TV channels (OK, four, if you count PBS) each week ABC broadcast a series titled The Six Million Dollar Man. It told of the adventures of Steve Austin—actor Lee Majors—who had turned bionic for a measly $6 million. Yes, nuclear-powered legs (which allowed him to run in slow motion), an arm, and an eye. In the introduction each week a serious voice intoned: “Steve Austin, astronaut. A man barely alive…we can rebuild him…. Better than he was before. Better, stronger, faster.” Even before a nurse could say, “Sometimes, doctor, faster isn’t better,” you saw a Northrop M2–F2 flying with a body tumbling violently out of control, kicking up tons of dust and debris. How could anyone survive that? Even a manly man like Lee Majors?

Well, someone did. The pilot wasn’t Steve Austin, but test pilot Bruce Peterson, and the aircraft hit the ground at 250 mph. It was a career-ending crash, which Peterson got to relive week after week between 1974 until 1978, when The Six Million Dollar Man was mercifully canceled. But despite being loaded on a stretcher and rushed by ambulance to the emergency room, Peterson still walked away figuratively. Which only goes to show that it was a good landing.

Phil Scott is a freelance writer and pilot living in New York City. Illustrations by John Sauer.