Your airplane operates on a strict diet of air and fuel (we’ll set aside oil for the time being). Each time you fly, you’ll need to regulate its intake of those key ingredients to help the engine operate most efficiently on the ground and in the air.

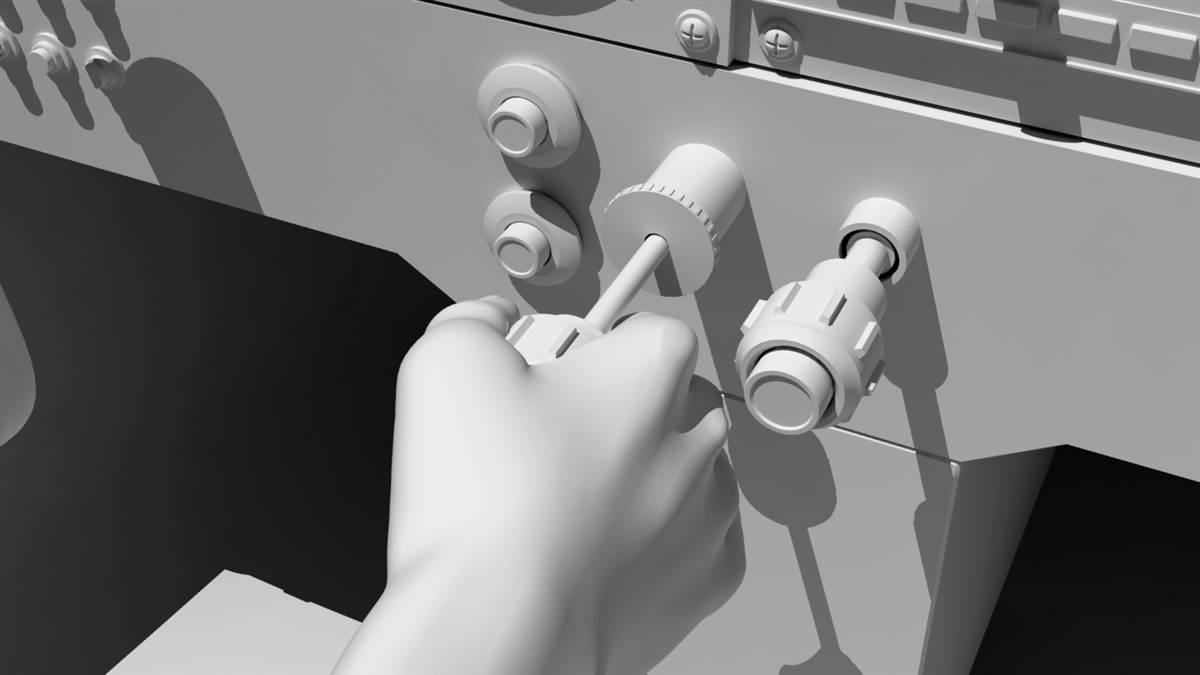

The red mixture-control knob on your airplane allows you to manually control the proportion of fuel that’s delivered to the engine via the carburetor or fuel injection system. The carburetor’s job is to deliver air and fuel in the correct proportion: 15 parts of air for every one part of fuel.

On takeoff (except at high-density-altitude airports) and landing, the engine needs a rich mixture—that is to say, the red knob is all the way in. As you climb, air becomes less dense, but the amount of fuel flowing remains the same. That means the ratio is changing all the time as you climb, and less and less oxygen is blending with the same amount of fuel.

If you don’t lean the mixture at cruise altitude, reducing the amount of fuel sent to the engine, you’ll wind up needlessly burning extra fuel, and that will throw off your careful preflight planning. Check your pilot’s operating handbook for specific recommendations on leaning.

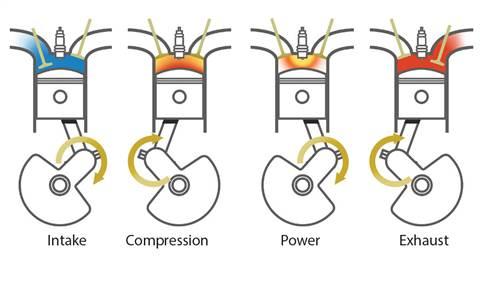

The four-stroke engine cycle

Intake:

The piston moves downward and draws fuel and air into the combustion chamber inside the cylinder.Compression:

The piston rises and compresses the mixture. Once that has happened, spark plugs ignite the mixture.Power:

The resulting explosion pushes the piston downward.Exhaust:

The rising piston forces spent gases through the exhaust system.1. When you reach cruising altitude,

set your desired cruise rpm and trim the airplane for hands-off flight (see “Technique: Trim for Hands-Off Flight,” October 2010 Flight Training).

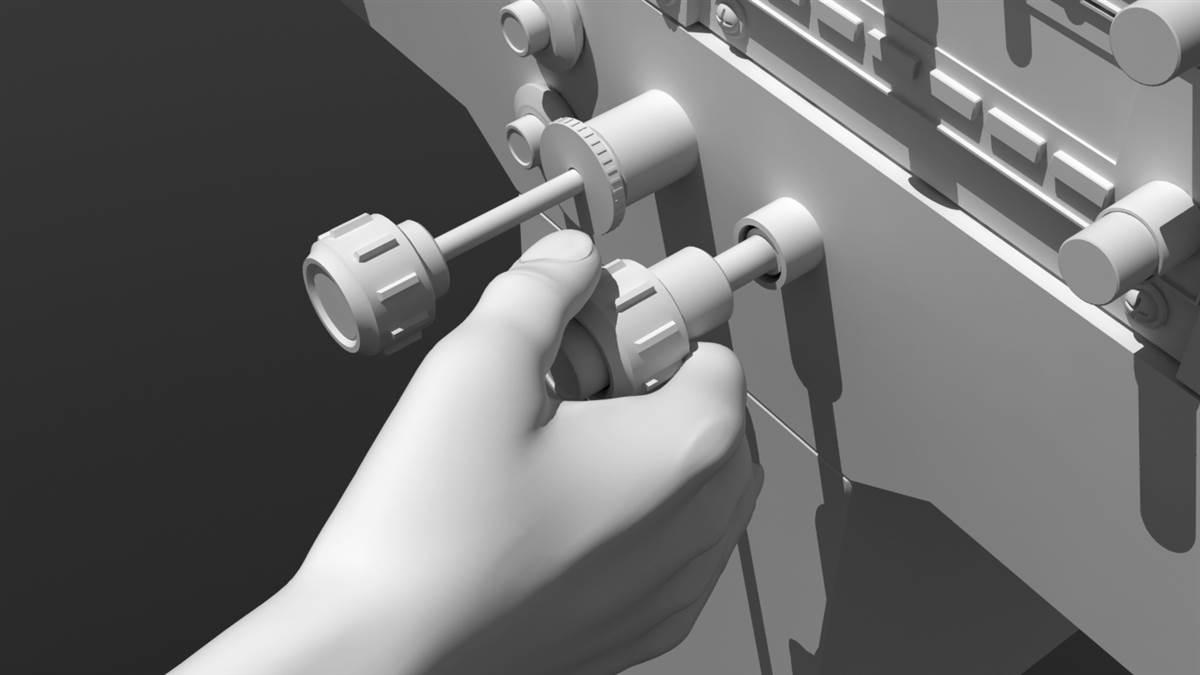

2. The goal is to reduce

the amount of fuel and restore the balance that makes the right mixture. Gradually (no rapid movements!) bring back the mixture control. Keep a close eye on the tachometer. The needle may rise, and then it will drop and the engine may sound rough. That's peak exhaust gas temeperature.

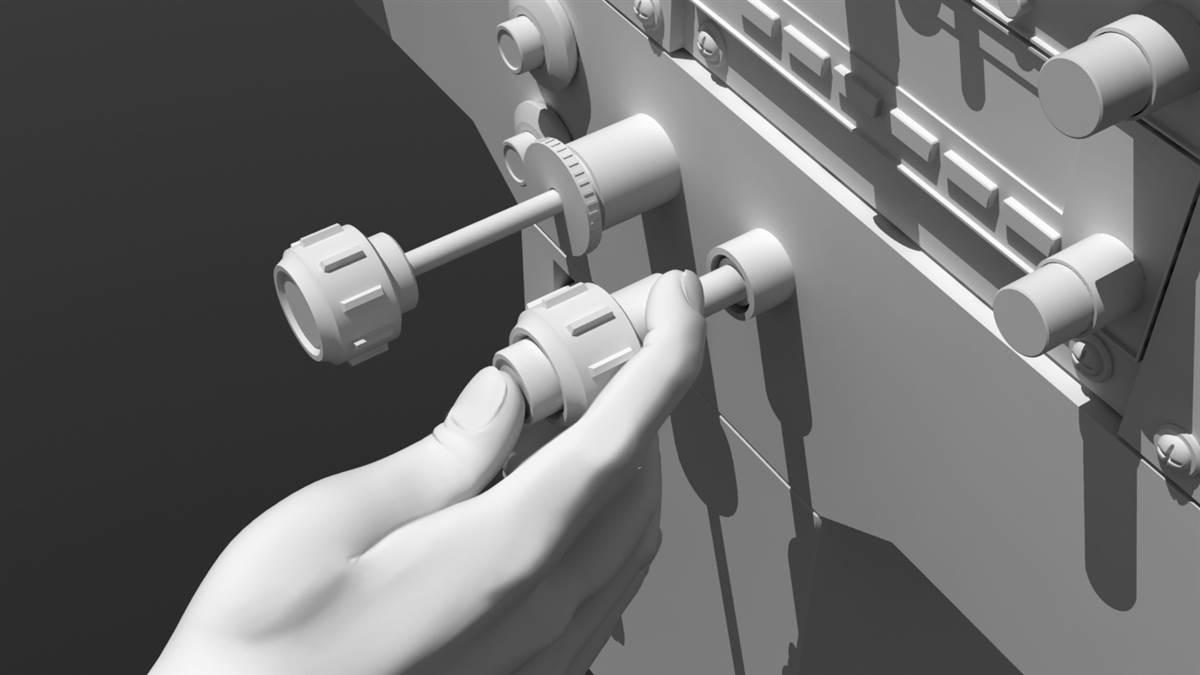

3. Now enrich slightly

until the engine smoothes out; the tach may rise slightly. Leave that setting as long as you are in cruise. If you climb, you’ll need to enrich the mixture once again, and will need to lean when you return to straight-and-level flight. Note that some aircraft are equipped with exhaust gas temperature (EGT) gauges for precise mixture adjustments. Your procedure for leaning with an EGT will be different and you should follow the manufacturer’s instructions for using it.

4. Return the mixture

to full rich during the descent and prior to landing. This is especially important in case of a go-around, where full power is required and the engine will hesitate, or run too hot, with too lean a mixture setting.