The LSA Star Fighter

Flight Design CTLS: Leaving the mother ship

Flight Design's 100-horsepower CT light sport aircraft (lsa) has led the U.S. market since the light sport industry started six years ago with the delivery of the CTSW model. That honor could come to an end next year, when Cessna Skycatcher deliveries are scheduled to overtake those of the two-seat, Rotax-powered CT; 330 CTs have been delivered in the United States. Worldwide, the total is 1,600.

John Hurst, of Sebring, Florida, chairman of a light sport industry committee, sees Cessna’s potential domination of the market as a blessing, because it legitimizes the industry and draws attention to competitors.

The CTSW model is still supported but no longer sold new in the United States (it is sold overseas). Its evolution in the American market has resulted in today’s CTLS model (99 delivered in the United States) with tougher landing gear, a longer fuselage, and, like the scarecrow in The Wizard of Oz, a brain. The brain comes packaged in the Dynon Avionics SkyView avionics suite, a system that is only for Experimental category and Light Sport aircraft, but comes strikingly close to Garmin’s G1000 system. It was introduced in January 2010.

Recently, I wrote about Garmin’s synthetic vision system that features a little green circle some pilots call a “meatball” (see “Quick Tips for the G1000,” February 2011 AOPA Pilot). Put that circle on the end of a runway on your display, and that is where the aircraft will go, given current trends. Well, guess what? Dynon has synthetic vision, too, with a similar meatball. The main difference? Its circle is white, but performs the same magic.

Dynon’s bigger than you think

“Our intent is to do everything the G1000 does.”

–Robert Hamilton, Dynon Avionics

“It’s amazing how little people know us,” said Robert Hamilton, director of sales and marketing for Seattle-based Dynon Avionics. “The market for Light Sport and Experimental is quite a bit bigger than for certified airplanes. We are the largest manufacturer in numbers of glass panels for single-engine aircraft, just because of market dynamics—which planes are being built and flying,” he said.

“Our intent is to do everything the G1000 does. We’re not there yet. Our new product is the Mode S transponder. We intend to have radios. We are going to be able to do legal IFR approaches with it,” Hamilton said. Sport pilots may not fly in instrument conditions, but instrument-rated pilots may use an LSA for instrument currency and training in VFR weather if the airplane is equipped and approved. Not even instrument-rated pilots may fly a Light Sport aircraft in instrument conditions until the industry has set standards that the FAA approves. The industry committee is working on IFR standards.

The CTLS I flew has a triple GPS system. There are two buried in the SkyView system, and another in the Garmin GPSMAP 696 in the center of the panel. “Flight Design had us design it so that if you lose one screen, the functionality for that screen will automatically switch to the other screen,” Hamilton said. “We can use the Garmin 696 as a navigation source, but with the feature set [of the SkyView], it is somewhat redundant.”

The aircraft has dual pitot tubes, in case one gets blocked. There is a pitot tube on each wing, and each has its own independent ADAHRS (air data attitude heading reference system), which feeds information to the SkyView displays.

New gear, new fuselage

When the CTSW first came out, a few flight schools reported landing-gear failures caused by hard student landings. All models sold in the United States have updated gear, and use a sandwich of carbon fiber and fiberglass for the main landing gear. The CTSW had machined solid aluminum rods that tended to promote bouncing after a hard landing.

Hurst said the new landing gear is more forgiving for training operations, and much more shock absorbent.

The CTSW could also be overly sensitive in pitch. A little pull on the control stick caused a big change in pitch. The fuselages of the CTLS and CTLS Lite are now 16 inches longer. (The MC is a completely different design but happens to be about the same length.) “The longer-coupled empennage gives you more dampening in pitch for newer pilots, and dampens yaw quite a bit,” he said.

This Flight Design demonstrator aircraft has navigation overkill, with three GPS systems—two in the Dynon Skyview screens (left and right) and one in the Garmin GPSMAP 696 (center). The screens are easily reconfigured using dedicated buttons that save a minute or two of menu-diving compared to other systems. As with more expensive systems, information can be combined on one screen if the other fails.

This Flight Design demonstrator aircraft has navigation overkill, with three GPS systems—two in the Dynon Skyview screens (left and right) and one in the Garmin GPSMAP 696 (center). The screens are easily reconfigured using dedicated buttons that save a minute or two of menu-diving compared to other systems. As with more expensive systems, information can be combined on one screen if the other fails.

Just a quick review

A light sport aircraft, as you recall, is a two-seater with a maximum takeoff weight of no more than 1,320 pounds, and cruising no faster at maximum continuous power than 120 knots calibrated airspeed.

It is intended for a new class of pilot, the sport pilot, a certificate requiring only 20 hours of instruction and a valid driver’s license instead of a medical certificate. (The pilot must never have been refused an FAA medical in order to use a driver’s license.) Sport pilots can’t fly at night or above a cloud layer, but there’s nothing keeping private pilots and those with higher ratings from flying at night or over clouds.

What’s a CT?

Hurst says there is still confusion in the marketplace between models. Not a surprise, considering there are more than 100 Light Sport models and many appear similar. The CT wings do not fold and there are no wing struts, compared to the Remos brand that is often confused with the Flight Design.

Flight Design assembles and tests the aircraft at its headquarters in Germany, but builds the airframe in Ukraine. About 40 percent of the value of the plane is U.S. content, including avionics, the BRS airframe parachute, wheels, brakes, and soon even propellers.

The 16-inch-longer fuselage compared to the previous CTSW model, no longer offered in the United States, improves handling by dampening both pitch and yaw inputs, qualities much appreciated by newer pilots. The door is large, and is designed to allow passengers to sit down and swing their legs in—a challenge in some light sport aircraft.

The 16-inch-longer fuselage compared to the previous CTSW model, no longer offered in the United States, improves handling by dampening both pitch and yaw inputs, qualities much appreciated by newer pilots. The door is large, and is designed to allow passengers to sit down and swing their legs in—a challenge in some light sport aircraft.

Current models are the composite CTLS, the CTLS Lite, and the MC with a metal airframe (but composite-covered cabin and engine cowling). The CTLS Lite and CTLS are made of mostly carbon fiber. The Lite comes with simplified avionics, lighter parts, and fewer “standard” features. The new $40,000 floatplane conversion is based on the Lite model, thanks to its lighter weight (LSA floatplanes have a higher maximum weight, 1,430 pounds). The MC is aimed at the training market and costs $113,823 when equipped to compete with the Cessna Skycatcher.

With its winglets and swept tail, it looks like a starfighter that is carried aboard a mother ship.

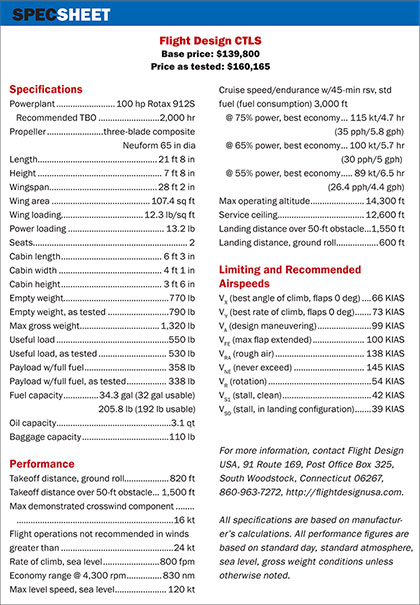

The CTLS Lite has a base price of $119,980, while the more fully featured CTLS has a base price of $139,800. The CTLS tested for this article had most of the available options and is priced at $160,165. Its options include the SkyView system at $12,075, leather seats for $1,190, the AmSafe seatbelt airbag system for $6,375, an integrated Dynon SV autopilot (it is built into the multifunction display) for $2,980, and an LED landing light for $725.

That’s a large bundle of cash, but it turns out most customers are requesting options that make the aircraft more expensive. Over the years, Flight Design officials have made more of the options standard.

The cabin is not only wider than a Cessna 172’s, it is wider by five inches than a Cessna 182’s.

The cabin is not only wider than a Cessna 172’s, it is wider by five inches than a Cessna 182’s.

It’s not uncommon to hear customers say, “I thought the Light Sport was supposed to cost $60,000.” But even when the base price for a CT was $79,000 five years ago, customers added options until the cost was $100,000.

Standard equipment covers 25 items, but highlights include the Dynon EFIS-D100 electronic flight instrument system and Dynon EMS-D120 engine monitoring system; Garmin avionics, including an SL40 comm radio, GTX 327 Mode C transponder, and GPSMap aera 510 with XM Weather; a PS Engineering PM3000 intercom; the BRS Aerospace 1350 high speed recovery parachute; wheel pants; and other goodies.

Yearly insurance on the CTLS for a 500-hour pilot was estimated by one company at $2,100 per year for $150,000 hull and $1 million in liability, $100,000 per passenger.

Flight Design importer Tom Peghiny hoped to deliver 120 a year in the United States back in 2005, and got as close as 90 a year in 2006 before the numbers sagged.

What fans say

Fred Runde of Belmont, Wisconsin, loves the three (or is it four?) Flight Design aircraft he has owned. A CTLS is on order and he owned a CTSW. As a manager of six scrapyards, one of them out of state, he uses it nearly every day to commute to his facilities. At one of the scrapyards he can land next door and taxi to the office.

“The only detriment is the learning curve to land it—you have to have some patience in learning. It floats in ground effect, and all at once energy is gone, and you’ve got to be ready—it’s a little more difficult,” Runde said.

“It’s an absolute joy,” he said, slipping back into enthusiast mode. He even flew it to the Bahamas. “It’s a real airplane. You turn the autopilot on, turn on the XM Weather, sit back, and enjoy the ride.”

Flight Design assembles and tests the aircraft at its headquarters in Germany, but builds the airframe in Ukraine.

With my urging, he found one other thing that could be improved. “The one drawback is the noise level in the cabin. It is much higher than a conventional Continental or Jabiru [engine] or whatever,” he said. He cures the problem with a Bose headset.

Kent Johnson, manager of Stanton Sport Aviation south of Minneapolis, is a dealer for Flight Design. He is selling his CTSW and has a CTLS for rental and instruction. His students never broke a gear on the CTSW, but a gear did bend in a particularly hard landing. He appreciates the new composite gear on the CTLS and confirms that it is less likely to bounce than the aluminum-rod CTSW gear.

Flying to meet Ruby

Rain at Avon Park Executive Airport, Florida, and a flat main tire on the CTLS, delayed the formation flight for photos with this article, so most of my impressions were formed on a second flight the following day. We were still able to get the photo flight done, but turbulence was strong. Winds were from 294 degrees at 23 knots, but sometimes from 240 degrees. I tended to overcontrol a bit while in formation, and the CTLS needs a light touch using fingers rather than a fist on the control stick. Hurst demonstrated landing in 350 to 400 feet for our ground-based video camera, but the 1,320-pound airplane was kicked around a bit on final. To be fair, the CT models handle turbulence better than many Light Sport aircraft on the market.

The second flight came during the U.S. Sport Aviation Expo at Sebring, Florida, a few miles away. After the trade show closed for the day, the CTLS was rolled out of its display area at Sebring Regional Airport and pushed to the taxiway for engine start. Conditions were much better, with smooth air, a golden sunset, and no rain storms in the area.

Back-pressure was maintained during the takeoff roll to unload the nosewheel, a technique that is common among Light Sport aircraft. Rotation was at 47 KIAS, while climbout was at 73 KIAS. The destination was a fly-in community where Hurst lives, Placid Lakes Airport (09FA), where Ruby the parrot waited patiently for her master. Hurst discovered her one day cowering in a tree, and gave her a life of luxury in a floor-to-ceiling cage at his duplex home.

Cruise flight produced 115 KTAS, as promised, with the flaps set to negative six degrees. To meet the low stall-speed requirement, a wing with a high camber (the arch in the wing from the leading edge to the trailing edge) had to be used. It lowers stall speeds but also lowers cruise speeds. To reduce the camber, flaps can be set to minus six degrees for an improvement in cruise speed.

A unique feature of the ignition system (left) is the fuel shutoff valve. The valve covers the ignition switch so that the pilot can’t insert the key to start the airplane if the fuel is off. The control stick grip (right) includes a push-to-talk switch and an autopilot disconnect switch.

A unique feature of the ignition system (left) is the fuel shutoff valve. The valve covers the ignition switch so that the pilot can’t insert the key to start the airplane if the fuel is off. The control stick grip (right) includes a push-to-talk switch and an autopilot disconnect switch.

Power was reduced to 4,300 rpm for downwind, slowing the airplane to 60 KIAS (54 KIAS can be used, according to the pilot operating handbook) for final. It’s just as important to keep weight off the nosewheel during landing as it is for takeoff. The book suggests flaring at three feet. That seems pretty low to pilots of larger, heavier aircraft, and many of them end up flaring high and dropping the aircraft in for a hard landing. I didn’t have that problem, but tended to land with the nosewheel barely off the runway. At least landings were smooth.

Once off the runway and parked on the grass, there was time for a full inspection of the aircraft’s features. With its winglets and swept tail, it looks like a starfighter that is carried aboard a mother ship. The winglets act like a gate at the end of the wing, improving airflow over the ailerons, and therefore roll control.

Features that impressed me include the fit and finish—and that may be the biggest reason Flight Design leads the U.S. market—the separate lock for the hand brake (there are no toe brakes), the comfortable leather seats with lumbar control, and even the luggage storage areas. There are storage lockers in the cabin floor beneath the feet of the pilot and co-pilot, a baggage compartment behind the two seats, and a jacket rack in the back.

After the full inspection of the CTLS, there was time to visit with Ruby. We’re fond of saying that general aviation serves America. It serves Ruby the parrot, too. It gets her master home on time, and after the article is read, it may soon line her cage. Hope you enjoy it, Ruby, one way or the other.

Email the author at [email protected].