Walking back on

A wing walker takes to the skies again

THE STEARMAN RUMBLES DOWN

the runway and launches into the air. The slender blonde woman in the front seat is waiting for the signal from her pilot. It comes—a nod—after he reaches a certain altitude, levels off, and pulls back the power. She hoists herself up onto the door and begins to climb on top of the upper wing.

Jane Wicker was seated on the floor of the living room in her Northern Virginia townhome a few years ago, sorting through a pile of videocassettes. She had a batch of memories she wanted to transfer to DVDs—memories of her former life as a wing walker. She put a videocassette into the player and watched her younger self standing on top of a 1943 Stearman, waving to the crowd as her then-husband, Kirk Wicker, put the airplane through its paces.

Wicker realized she missed it—all of it. The flying, the wing walking, the traveling to airshows in an RV. “I just said, ‘I’ve got to get back into this,’” Wicker said. She pulled herself up from the floor and tried to recreate from memory the steps and movements of her routine—where to place her feet, where to wrap her arms. It all came back.There was only one problem—she no longer had an airplane to walk.

Jane Wicker began walking on airplanes in 1990 when she quixotically answered an ad in The Washington Post. The Flying Circus in Bealeton, Virginia, which puts on airshows every weekend in spring, summer, and fall, was hiring. “No experience necessary. On-the-job training provided,” the ad promised. About 50 people showed up for the audition.

Jane Wicker began walking on airplanes in 1990 when she quixotically answered an ad in The Washington Post. The Flying Circus in Bealeton, Virginia, which puts on airshows every weekend in spring, summer, and fall, was hiring. “No experience necessary. On-the-job training provided,” the ad promised. About 50 people showed up for the audition.

Those who made the cut worked with an experienced wing walker who taught them a simple routine. First they practiced on the ground, over and over, for a month.

Then they graduated to practicing on a stationary airplane on the ground. Wicker was the only female in the group. She did a few shows that year, and in 1991 performed her first full season.

THE WOMAN REACHES THE stanchion on the top wing, careful not to move an arm or a leg unless the others are securely wrapped around a strut or the stanchion. She positions herself in front of it and fastens a safety harness around her waist. As the biplane begins a dive, she tenses her body so that the 160-mph winds won’t force an arm or a leg to fly out behind her. When the airplane gets to the top of its loop, she can relax a little, and wave to the spectators.

She hadn’t intended to become a wing walker—or a pilot, for that matter. “After high school I was going to take classes at Northern Virginia Community College and [become] a flight attendant,” she said. “A friend of mine was going out to practice precision approaches. It was a really pretty, calm day. He took me up. I fell in love with [flying].” The following January, she signed up for ground school, and went on to get a degree in aviation technology while pursuing a private certificate and then an instrument rating and commercial single-engine certificate at Dulles Aviation in Manassas.

She met Kirk Wicker in 1990 at the Flying Circus audition and they married in 1993. An experienced aerobatic pilot, he performed at airshows in a clipped-wing Taylorcraft and then a Mudry CAP 21, a French single-seat aerobatic airplane. They purchased a Stearman in 1997 and created the wing-walking routine, which they called “Beauty and the Beast.” When their second child was born that year, Jane became a stay-at-home mom and full-time wing walker.

The Wickers worked shows around the country and supplemented that income by selling Stearman rides at the Flying Circus (see “Barnstorming,” May 1995 AOPA Pilot). Jane ran the business, and would drive a motor home with their two sons to the shows, while Kirk ferried the Stearman.

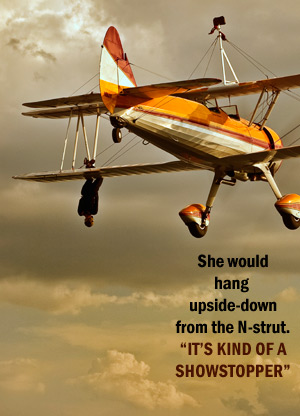

At the height of their success, the Wickers booked 15 shows in a season. “Our act was so different,” Jane said. She would hang upside down from the N-strut. Then Kirk would roll the Stearman inverted and Jane would be sitting upright on the underside of the wing. “It’s kind of a showstopper,” she said. “No one else is doing it. I still do it today.”

At the height of their success, the Wickers booked 15 shows in a season. “Our act was so different,” Jane said. She would hang upside down from the N-strut. Then Kirk would roll the Stearman inverted and Jane would be sitting upright on the underside of the wing. “It’s kind of a showstopper,” she said. “No one else is doing it. I still do it today.”

Jane Wicker prepares to take to the skies at the Greenwood Lake Airshow in New Jersey

Jane Wicker prepares to take to the skies at the Greenwood Lake Airshow in New Jersey

The Wickers’ marriage ended in 2002. They had struggled on past the point of salvaging it, Jane said, but were trying to make it work because “I didn’t want to give up airshows.” Jane got the “WING WALKER” license plates in the divorce agreement. She trained another person to do the act with Kirk. He quit the next year, and sold the Stearman.

Jane took a job as a budget analyst for the FAA and settled into the routine of working, commuting, and raising her sons. Wing walking and flying were relegated to chapters in her life—until she realized, viewing those videotapes, how much she missed it.

Wicker at first tried to find someone who needed a wing walker—not the most wide-open field in aviation. “Then I tried to find someone to let me use their airplane. There’s not a lot of Stearman pilots who will let me walk on their airplanes,” she said.

Finally Wicker placed an ad with Barnstormers.com seeking a 450-horsepower Stearman with inverted oil and fuel systems. She soon heard from Steve Wagner in Inver Grove Heights, Minnesota, who had a project. The airplane needed to be reassembled and the wings painted.

SHE UNCLIPS THE SAFETY BELT and climbs back down into the cockpit. She waits for the next signal. Just before the airplane reaches the beginning of the crowd line, she climbs back up and out of the cockpit. She will now begin walking along the wing.

She asked Ryan Dulas, who had been mechanic for the Red Baron Pizza Squadron of Stearmans, to check it out. Dulas wasn’t available, but he sent a trusted colleague—Jim Carlson, head of maintenance for the squadron, who reported back to Wicker, “You couldn’t find a better deal.” Wagner had purchased it in the 1980s and spent 20 years working to bring it back to life. The wings were hand-built and -covered, and the stitching was immaculate. The Pratt & Whitney R985 450-horsepower radial engine had steel cylinders instead of chrome.

Carlson and Dulas offered to finish putting it together at Carlson’s shop in Olivia, Minnesota. They sent pictures and videos of the restoration to Wicker. She did not see the airplane until January 2010, as it was still being reassembled. It looked even better in person than in the photos. “The workmanship was far beyond what I had imagined,” she said.

A cardinal rule is that she always has two points of contact with the airplane when moving around the wing.

A cardinal rule is that she always has two points of contact with the airplane when moving around the wing.

Wicker chose a paint scheme to match the airplane’s red and yellow wings and tail. She assisted in the redesign of the panel, which has basic instruments—a compass, engine gauges, and altimeter—plus a Garmin 250XL GPS, “which is helpful because it’s hard to have charts in a Stearman.”

And she gave it a name— Aurora.

“The name didn’t come easily,” Wicker said. “I had an image in my mind of what I wanted the name to mean. I went through all these possible names and meanings in the dictionary.” When she hit upon Aurora, she envisioned a sunrise, “which made me think of the sunburst wings, the red and yellow.” One of the meanings of Aurora is “new beginnings.” “That’s so appropriate of my airshow career,” she said.

By June 2010, the aircraft’s restoration was complete. Wicker had booked three airshows without even having taken delivery of Aurora. “It was a little scary,” she admitted. Though she had kept herself in top physical condition, she hadn’t wing walked in seven years. And there was the matter of finding a pilot for the act. She had lined up some prospects but hadn’t flown with any of them.

Wicker and Jim Carlson flew Aurora to its new home at Warrenton-Fauquier Airport and, after some reflection, Wicker asked her ex-husband to help her get her act going again. “We went through this tumultuous part in our marriage...but the flying brought

us back together,” Jane said. “That’s

the one place in our relationship we never fought about. We worked well in an airplane.” Kirk offered to fly for her until she could train another pilot.

Wicker performs her signature stunt, in which she hangs upside down from the wing, while the Stearman rolls inverted, then sits on the wing.

Wicker performs her signature stunt, in which she hangs upside down from the wing, while the Stearman rolls inverted, then sits on the wing.

SHE STEPS OUT ONTO THE stearman’s lower left wing, dividing her attention between what she’s holding onto and where she must place her feet. She can only step on the wing spar where the ribs cross, lest she put a foot through the fabric. Stepping only on the balls of her feet, she locks her arms around flying wires and struts.

She seats herself on the lower wing and fastens the safety harness to a flying wire. She turns her back to the wind and hooks her legs and ankles around the N strut. Then she drops down and hangs by her knees beneath the wing. The Stear-man dives to 140 mph and performs a half-roll to fly inverted down the runway. She relaxes her body as the roll happens. With the airplane upside down, there’s a lot of wind but not much for her to hold onto, so she anchors herself with one arm against the wing and waves with the other.

On a Wednesday in July, days before her return to the airshow circuit, Jane stepped out of Aurora’s cockpit as Kirk flew. “It was as though I had never stopped,” she said. “It wasn’t physically demanding. We each knew what the other was doing. He knew exactly where I was going to go. We remembered the whole routine.” They performed the entire sequence as if no time had slipped by.

Kirk is Jane’s pilot, once again. She also flies with Bill Gordon of the Iron Eagle Aerobatic Team. Jane’s significant other, Rock Skowbo, has joined the team too. Skowbo, an airline pilot and mechanic, soloed Aurora a week after Wicker did.

Kirk is Jane’s pilot, once again. She also flies with Bill Gordon of the Iron Eagle Aerobatic Team. Jane’s significant other, Rock Skowbo, has joined the team too. Skowbo, an airline pilot and mechanic, soloed Aurora a week after Wicker did.

With Jane Wicker Airshows on the circuit, Wicker is working hard not only to get her name back out there but to make her act even more exciting. She’d like to get a low-level waiver so that she can perform solo aerobatics in addition to wing walking. She has picked up some sponsors and would love to get more. “With a full-time sponsor, it could go somewhere big,” she said.

The circuit has changed—many of the people who knew Wicker 10 years ago aren’t on the scene anymore. That doesn’t matter. She’s back where she feels she belongs—back on the wing, hanging upside down, waving to the crowds.

Email the author at [email protected].