Flying the Jumbo, Jumbo

An hour in the left seat of an A380

Illustrations by John Sauer

When I was a young commercial pilot, I wanted to fly jets. Didn’t we all?

A jet pilot’s life would be so easy; just flip a few switches, wait for the engines to roar to life, and take the runway. No preheating, no mag checks, nothing. And then, of course, I imagined that wonderful burning-jet-fuel aroma that told everyone I’d made it to the big time.

October 2011

Turbine Pilot Contents

- Turbine Intro: Powering into the future: Special section for the turbine inclined.

- The NeXT Beechjet: New power, panel, and pylon mods for the “old” Beechjet

- Routes Less Traveled: HondaJet sprints toward 2012 certification schedule

- Flying the Jumbo, Jumbo: Taking on the A380

- Honeywell’s SmartView Moves Ahead: Merging infrared with synthetic vision

Since we all know bigger jets are better, jet-pilot Mecca just has to be flying a jumbo jet, a tag that barely fits the massive Airbus A380 weighing in at about 1.235 million pounds. And it only takes a cool $375 million to add one to your hangar. I managed to grab an hour in the left seat of an early production A380 at Airbus’ Toulouse, France, factory when I was asked to evaluate a new computerized braking system for the big bird.

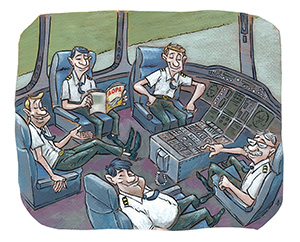

There is simply no way to accurately express my sense of awe walking around beneath an A380, where the cockpit sits nearly 30 feet in the air. Or maybe it was kicking all 22 tires prior to entering the cockpit, or watching the fuel-loading process gulp enough Jet A—about 85,000 gallons—to carry the aircraft 8,300 nm between fill-ups. Inside, the cabin is vast enough to squeeze in as many as 853 passengers, while the central forward staircase is wide enough that three can walk abreast up or down simultaneously and never rub elbows. Even the cockpit is huge, with enough jump seats for five additional pilots.

The giant Airbus is so quiet at startup that if you weren’t watching the cockpit displays, you’d be blissfully unaware the Rolls-Royce engines were even turning. With 40 feet between the main wheels, I expected taxiing to be, well, taxing—even though I’m not new to flying jets. Just before my Airbus flight instructor Claude gave me a thumbs-up for taxi, he pointed to a TV screen at the bottom of the center panel display. Here the left-seater can view the output from a forward-looking video camera sitting between the main landing gear that shows the captain exactly where the nosewheel is tracking. I had to remember to look out the windows too, even though I couldn’t see the wing tips from the cockpit.

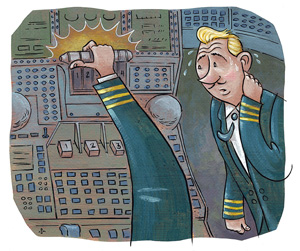

With the cockpit sitting a very, very long way ahead of and above the engines, my shoving the throttles halfway up on takeoff seemed, at first, to create no reaction—no noise or even any vibration. You know what happened next, right? I pushed the throttles right to the firewall, much to the discomfort of those big motors, as well as Claude. It’s all about the physics of moving from zero thrust to nearly 300,000 pounds; it takes a couple of seconds before the pilot notices anything, especially if you want the engines to last.

With the cockpit sitting a very, very long way ahead of and above the engines, my shoving the throttles halfway up on takeoff seemed, at first, to create no reaction—no noise or even any vibration. You know what happened next, right? I pushed the throttles right to the firewall, much to the discomfort of those big motors, as well as Claude. It’s all about the physics of moving from zero thrust to nearly 300,000 pounds; it takes a couple of seconds before the pilot notices anything, especially if you want the engines to last.

Another really strange sensation occurred at the 125-knot rotation speed. Looking out the window I had the feeling we were moving too slowly to fly. My co-pilot reminded me again, so I eased the digital side stick back and the A380 leaped into the gray French afternoon. Claude called “positive climb rate,” and I commanded gear up. On the first takeoff, I have no idea how long that took because I was so amazed at the lightness of the aircraft versus my flight-control inputs. We weighed about 900,000 pounds on this flight, but the Airbus flew like that zippy little Cirrus I’ve grown to love over the past few years. As we climbed to pattern altitude, I tried some 45-degree steep turns. The aircraft responded effortlessly. There’s no trim necessary, either. The computer senses everything and compensates automatically. On downwind, I simply tugged the throttles back to an approach power setting.

The landings were planned to demonstrate a new Airbus braking system—brake-to-vacate—that minimizes time on the runway and prevents just missing an intersection on rollout. Besides wasting time, a taxiway miss probably means someone on final will need to go around, which reduces airport acceptance rates. The A380’s FMS already knows the landing weight and, when runway conditions are added in, can determine at which intersection the aircraft will halt to clear the runway. On touchdown, the pilot never touches the rudder/brake pedals; autobrakes do all the work and slow the aircraft to less than 30 knots just prior to turnoff.

The landings were planned to demonstrate a new Airbus braking system—brake-to-vacate—that minimizes time on the runway and prevents just missing an intersection on rollout. Besides wasting time, a taxiway miss probably means someone on final will need to go around, which reduces airport acceptance rates. The A380’s FMS already knows the landing weight and, when runway conditions are added in, can determine at which intersection the aircraft will halt to clear the runway. On touchdown, the pilot never touches the rudder/brake pedals; autobrakes do all the work and slow the aircraft to less than 30 knots just prior to turnoff.

Just in case, a friend shot a photo of me in the left seat to quell the eventual rumors that the flight just might have been fictional.

Robert Mark is the editor of JetWhine.com, an award-winning aviation blog.