Flying in the land of elephants

Flying safari provides a real-world Wild Kingdom experience

Photography by the author

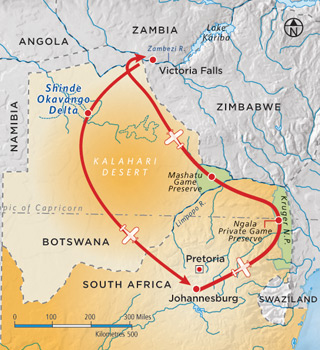

The elephant dung on the runway was our first clue that we had arrived in the African bush. We all gathered around it for a look after carefully taxiing by it—not through it. Planning for that first sighting had started months earlier; at that moment, though, little did we know just how close we would get in the next week to elephants, giraffes, rhinos, lions, leopards, zebras, wildebeests, hyenas, hippos, and a host of other wildlife. Marlin Perkins would have nothing on us.

The red and green 1970s Cessna 182s—ZS-IWP and ZS-NOY—looked lost, all alone on the lonely strip slashed out of the South African bush. Our biggest fears were that hyenas would eat the tires or an elephant might happen by and rub his backside against an elevator—all of which have happened, reports our guide, Elliott. In fact, IWP sports some “speed tape” on her horizontal stabilizer from a previous encounter with a hyena.

Aside from the remote surroundings, the landing at the Ngala airstrip was uneventful and easy. The paved, 3,900-foot strip is the primary guest access to Ngala, a remote but luxurious lodge on a 36,500-acre private game preserve adjacent to Kruger National Park. There is no fence between the preserve and the park, so the animals roam freely—including on the runway. As we were taught in our training back in Johannesburg, I made a low pass down the runway, checking for game and hoping to drive away any nearby beasts. Meanwhile, Elliott and our tracker Steve roared the open-topped Toyota Land Cruiser, the requisite safari vehicle, up and down the clearing for the same purpose. Satisfied that all was clear, I swung around the pattern for a landing.

The simple two-hour cross-country from Johannesburg went so well because of the extensive preparation we had for the two days preceding our flying safari. At Lanseria, a reliever airport northwest of Joburg, we spent a morning getting a briefing on local airspace and communications requirements from the tower chief. Then we spent the afternoon getting checked out in the 182s, all of which helped to meet the requirements for getting our U.S. pilot certificates validated in South Africa so we could fly locally registered airplanes. True everywhere in the world, our U.S. certificates only allow us to fly N-registered aircraft.

A misnomer

The local flights, “flips” as the South Africans call them, were not just a quick trip around the patch. I piled into IWP with highly experienced instructor Russell Donaldson, who taught me more than a little about dealing with high density altitude and how to approach remote strips that may be busier than they appear (make an overhead arrival 1,000 feet above the pattern altitude, crossing midfield to check the place out—then do the low pass to clear the game). While I would be the sole pilot in IWP with my wife Brenda riding shotgun, our flying companions—John and Martha King of King Schools—each got checked out in NOY.

After a day of checkouts and a day of briefings by Nick and Christina Hanks of Hanks Aero Adventures, we were set to launch on our adventure. The Hanks live half the year in upstate New York and half the year outside Johannesburg, arranging such adventures for pilots. Over the past 20 years, the couple has helped hundreds of pilots and passengers explore southern Africa in a way only possible by general aviation airplanes. Through their experience and feedback from customers, they have developed a remarkably complete briefing system that ushers pilots quickly through a local checkout and the paperwork associated with getting U.S. pilot certificates validated to fly South African-registered aircraft. Their services also include a highly detailed cockpit kit that provides all the particulars necessary for each leg in a separate envelope. Bring your favorite headset (although they can provide those too) and everything else is taken care of.

After the close encounter with the elephant leavings, we were quickly on our way to the Ngala lodge, the rugged Land Cruiser zooming along dirt paths through the scrubby, but lush backcountry. The lodge, like others we visited in Botswana and Zambia, was an oasis carved out of the bush—a swimming pool, open-air dining facility, bar, and individual guest cottages with private bathrooms. If you think you’ll be roughing it on safari, think again. The food is fresh, amazing, and as exotic as you want it to be (ostrich or chicken—your choice; yes, ostrich tastes like chicken; kudu, impala—or beef). At some lodges, evening meals are often accompanied by singing and dancing by the staff, which at least during our stay in April seemed to outnumber guests by a significant margin.

The day starts early—with a friendly, but persistent, 5 a.m. rap at the door. Meet for a light breakfast at 5:30 and by 6 a.m. we’re huddled under blankets—and warmed by hot water bottles—in the Land Cruisers for a sunrise adventure. Bustling through the crisp morning air, the tracker and guide watch the ground intently for tracks or signs of prey being dragged, an indicator that a lion or leopard might be nearby.

The experience tasks all the senses. The smell of African sage wafts through the air, becoming more intense in the heat of the day. Downwind of an elephant—well, you’ll know that, too. The cry of a monkey atop a tree is an alert that a leopard is nearby. Meanwhile, the bark of a jackal alerts that a leopard has a kill. The jackal, too small to take the kill from the leopard, is calling in the larger hyenas, who will take on the leopard—unless the leopard gets the kill up a tree first. Should the hyenas commandeer the kill, the fleet jackals know they can sneak in for a few scraps. Symbiotic relationships at work.

To give you a sense of scale, Kruger National Park and the surrounding private reserves that allow unfenced access to the park encompass an area the size of Massachusetts. You will see lots of game. In fact, we saw four of the big five in the first 24 hours—elephant, rhinos, lions, and buffaloes. The leopard eluded us until we got to Botswana, where we saw a young male up close and personal, and watched him leap into a tree and effortlessly drag his impala breakfast up a couple of branches. The sound of the crunching bones an indicator as to the power of his jaws. Apparently he was swifter than the hyenas this time—which we also saw up close and personal, including their pups at the den.

In general, the animals ignore the Land Cruisers. You can drive right up to a pride of young male lions—as we did. They stretched and cleaned themselves as we snapped photos. Same with elephants, rhinos, zebras, and giraffes, who go about their business as if you’re not there, unless someone stands up—which, the guides say, changes the profile of the vehicle and then causes the animals to take notice. What happens after that is anyone’s guess. Advice: Stay seated.

The morning drive usually includes a stop at sunrise where the guide and tracker make hot coffee, tea, and biscuits appear seemingly out of nowhere. After two to three hours of gawking at game and spectacular scenery and vegetation, you return to the lodge to a full breakfast (you will not go hungry on these trips). The day is yours to lounge around the pool or porch. Get hungry, because lunch is not to be missed. Take a nap and be back at the fire pit for a 4 p.m. departure on the afternoon drive. Be assured that it will include a stop at sunset for a drink and snack as the stars come out. There you’ll enjoy a southern sky and a view of the Milky Way that is unmatched. Heading back after dark, the tracker will flash a spotlight back and forth, frequently finding new and different types of game.

Finally, a full dinner awaits you back at the lodge. Gather around the bar or fire pit for an evening of storytelling and reliving the day’s adventures. At most locations a staff member will escort you back to your cottage because, well, the creatures—including the predators—don’t know the boundaries. Some lodges are fenced so you can walk about freely at night; at others you will want an escort.

A low overcast delayed our departure from Ngala, but gave us more time for the morning game drive and a surprise bush breakfast. As we roared around a bend in the path, Elliott slid the Land Cruiser to a stop, revealing the staff’s morning work: a full-course breakfast under a massive mahogany tree miles from the camp.

With the low clouds breaking up, we launched for our next stop in Botswana, but first we had to get fuel and clear customs out of South Africa at Polokwane, a major airport with an 8,400-foot runway, airline terminal, and all the amenities. At each stop clearing customs into or out of a country, the paperwork seemed interminable. As the Hanks had briefed us, the staff is competent and friendly, but things happen at a pace outside your control. You’ve not seen carbon-paper forms until you’ve seen carbon-paper forms associated with customs and immigration in southern Africa. Stamps and officialdom flourish here. On these legs we all wore professional pilot shirts with epaulets, which in theory helps usher you through in a way that mere airline passengers can only hope to experience. The Hanks’ kit includes the appropriate fees in the local currency for each stop, each in its own envelope and ready to hand over.

We found the fueling staffs to be efficient and friendly. Fuel prices were only a little higher than in the United States, about $7 a gallon on average, with major credit cards accepted everywhere.

Leaving Polokwane, we headed farther north toward the Botswana border. En route throughout southern Africa, there is little to no radar coverage, requiring pilots to broadcast position reports in the blind or at times to flight information region (FIR) controllers who simply note your call and wish you well. The Hanks file VFR flight plans for you for each leg, further easing the burden. A note in the Remarks section tells authorities you don’t seek search and rescue, so there’s no need to close the flight plans. Meanwhile, the Hanks, well connected with all the lodges and the air traffic systems, monitor your progress from afar and can step in with resources should a problem arise.

Our first landing in Botswana was at Limpopo Valley, a paved 5,000-foot strip that serves numerous lodges in the region, but is itself located far from anyplace in the dusty, gravely southern part of the country. But while the terrain looks bleak compared to the green of the Kruger area of South Africa, the region is ever richer with game. We seemed to find some interesting creatures behind every shrub—and on a continuous basis.

Our stay at the Mashatu Main Camp showed that the luxury and comfort of Ngala was not exclusive to South Africa. The dining area and bar overlook a watering hole in the 75,000-acre private game preserve. Individual cottages come equipped with all the amenities you’d find at a luxury hotel in the United States—and then some—in a setting so starkly beautiful that you’d think no animals would show, but they’re everywhere.

After 36 hours on the ground, we headed north again, clearing customs out of Botswana at Francistown, a modern international airport. Then it was on to Livingstone, Zambia, along the banks of the Zambezi River next to the magnificent Victoria Falls, the world’s widest falls. Flying north along Botswana’s eastern border, we were careful not to fly into Zimbabwe’s airspace. The government there in recent years has done its best to damage the once thriving tourism business.

Flying down the river, which forms the border between Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, we spotted the mist from the massive falls from miles away. Traffic over the falls follows charted altitudes and paths to separate the busy helicopter tour operators from airplanes. After our eye-popping aerial tour of the dramatic falls, we landed at Livingstone, another friendly international airport. We were met by a tour guide who took us on a tour of the falls area where you will get wet, but it’s a sight worth seeing. Our guide then whisked us a few miles downriver to the Toka Leya Camp, another first-rate lodge built on stilts almost out over the racing river. With only one night there, we didn’t get to sample a safari or river tour, but the lush, vibrant setting itself made the trip worthwhile—a stark contrast from the barrenness of southern Botswana, which in our Skylanes was only a couple of flight hours behind us.

The next morning, we launched again, flying back up the river toward Botswana, with a stop at Kasane to clear customs inbound. We headed southwest across north central Botswana toward the Okavango River Delta. Passing over thousands of watering holes, each with animal trails coming from all directions, we saw magnificent elephants, each casting its own shadow, as we tooled by from about 2,000 feet agl.

Our fear of not finding the remote Shinde dirt strip was for naught. The GPS led us right to the runway on the bend of the river. The Okavango is a teeming river whose delta never reaches the sea. Instead it simply spreads into increasingly narrow reed-lined channels that eventually wither into the dry landscape to the south. As you might imagine, the area is an aerial vista not to be missed—and a haven for animals. And while we saw loads of animals in Shinde, the harsh Mashatu area teemed the most.

As with the other locations, Shinde Camp was remarkable in its simple elegance and the fact that amazing accommodations and fresh food can be had in the middle of nowhere. It is the 3,300-foot clay runway that keeps this remote camp alive. During the rainy season it is the only access to the property and even otherwise, it’s a 10-hour drive to the nearest town of any size—or about a 30-minute flight. For us it was a quick 138 nm from Kasane to Shinde, where the guides awaiting our arrival had just cleared an elephant from the runway. How do you clear an elephant from the runway? At the elephant’s own pace.…

Shinde generates its own electricity and purifies its own water. Staples are trucked in every month or so and fresh food is flown in every few days. Camp owner Ker & Downey seems to have a logistics operation serving multiple camps in the delta that any high-speed manufacturer would envy.

More game drives and food, a visual and culinary feast, kept us busy at Shinde for another 36 hours before we set out on our last leg—a stop at the bustling Maun Airport for fuel and to clear customs out of Botswana and then back to Johannesburg. Bush planes a dozen deep waited for fuel at busy Maun, the hub of the delta region, which hosts dozens of camps. We were fortunate to visit the camps by GA, but many visitors arrive on airliners from South Africa and are then ferried to the camps by commercial Cessna 206s, Caravans, and GippsAero Airvans, a popular piston-powered mini-Caravan.

Fueled at Maun, we set out on the longest leg of the journey, a four-hour dash down Botswana into northern South Africa for the return to Joburg’s Lanseria Airport.

We started the trip at 9,500 feet msl in cool, comfortable air, but eventually were forced down to 5,500 feet near the capital city of Gaborone to stay VFR.

Throughout the trip, the biggest challenge was obtaining weather information. Even at the large international airports, weather information seemed not a priority. True, most of Botswana is high desert, so weather isn’t a major concern, but certainly in South Africa, weather is more an issue—and even then one had to work hard to find even the most basic of weather reports. American pilots, used to satellite-delivered datalink weather, universal cell phone and WiFi access, and flight service need to step back in time and dust off weather judgment skills that may have become rusty. Nonetheless, we had no significant issues with the weather and on our final leg scooted into Lanseria without a problem beneath a broken layer with good visibility.

Parking among the airliners at vibrant Lanseria to clear customs inbound showcased again the stark contrasts of the region. Hours earlier we had left remote Shinde and here we were, thanks to our mighty Skylanes, mixing it up with 737s next to a gleaming airline terminal.

The Hanks met us at customs and later dropped us off at a posh casino and theater district in a hip section of Joburg where we debriefed over dinner.

The ability to move about via GA airplanes provided not only the thrill of international flying in exotic places but also made possible a 1,300-nm trip that could not be done in a week by any other means. Were we to do it again, we’d add a few days to the trip for a more relaxing pace, but we wouldn’t trade the GA experience for any other means of exploring the remarkable Sub-Saharan region of Africa.

Email [email protected]

If you go

Hanks Aero Adventures can make arrangements to fit many budgets, but recommends as a starting point budgeting about $700 per person per day, which includes all accommodations, food, aircraft rental, and about anything else you can think of except fuel.

- Ngala, an &Beyond lodge near South Africa’s Kruger National Park, sports its own airstrip minutes from the camp, which includes a swimming pool and first-rate cottages. Its private game reserve has unfenced access to the world-famous Kruger National Park.

- Mashatu Main Camp in Botswana’s Limpopo River Valley region is truly an oasis overlooking a private watering hole in the stark landscape. The 35-minute drive from the paved Limpopo Valley Airport becomes your first safari of the day. Look for giraffe and other big game as you turn final.

- Toka Leya Camp, a Wilderness Safaris property just downstream from Victoria Falls, offers stunning views of the Zambezi River from private cottages facing the river. It is located only about 20 minutes from Zambia’s Livingstone International Airport.

- Shinde Camp, a Ker & Downey teak-festooned lodge partly built up in the trees overlooking the Shinde Lagoon of the Okavango River Delta. Each cottage has a private porch looking across the delta region, which teems with animals. A 3,300-foot clay runway is located within sight of the camp.