Pilot Briefing

News from the world of general aviation

Private space race gets new entrant

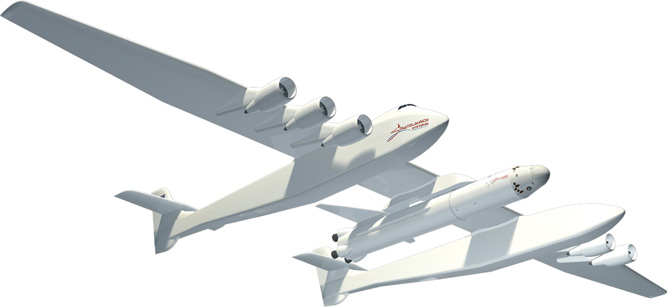

Tired of getting into orbit the same old way? Relief may be coming from Stratolaunch Systems, a collaboration between Microsoft cofounder Paul Allen and Burt Rutan, the designer of aircraft and spacecraft, in a project that will merge a Rutan-inspired design with certain hardware and engines from Boeing 747s to create a huge airplane that will launch rockets into orbit during high-altitude flight.

But don’t rush off and cancel your $200,000 reservation (booked through “your local accredited space agent”) for a suborbital flight on Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic spaceline just yet.

Not because of any code-sharing arrangements, even though the two services will operate from the same spaceport in New Mexico. It’s more a matter of timing: There’s no hurry, with the Paul Allen craft not scheduled to make its first flight for five years—and with Branson’s project, based on a second-generation Scaled Composites design, also in early development (although taking bookings for passengers and scientific projects).

In both cases, the ventures demonstrate that private enterprise is forging ahead to fill the vacuum left when NASA’s space shuttle program ended several months ago.

On December 13, Allen and Rutan announced that they had reunited via Huntsville, Alabama-based Stratolaunch Systems to “develop the next generation of space travel” after the 2004 flight of SpaceShipOne became the first flight of a manned, privately funded rocket flown beyond the atmosphere of the Earth. They were accompanied at a Seattle news conference by Stratolaunch board member and former NASA administrator Mike Griffin. The venture’s president and CEO is Gary Wentz, formerly a NASA chief engineer.

“I have long dreamed about taking the next big step in private space flight after the success of SpaceShipOne—to offer a flexible, orbital space delivery system,” Allen said. “We are at the dawn of radical change in the space launch industry. Stratolaunch Systems is pioneering an innovative solution that will revolutionize space travel.”

The product of Allen’s enterprise will be a mobile launch system that includes the carrier—the largest aircraft ever to have flown, Allen said—under development at Rutan’s company Scaled Composites; a multi-stage booster manufactured by Elon Musk’s Space Exploration Technologies (SpaceX); and “a state-of-the-art mating and integration system allowing the carrier aircraft to safely carry a booster weighing up to 490,000 pounds.” That component will be built by aerospace engineering firm Dynetics, said the announcement.

The aircraft, to be powered by six Boeing 747 engines, will have a gross weight of more than 1.2 million pounds, and a 380-foot-plus wingspan, requiring a 12,000-foot-long runway.

“The airplane will be built in a Stratolaunch hangar, which will soon be under construction at the Mojave, California, Air and Space Port. It will be near where Scaled Composites built SpaceShipOne, which won Allen and Scaled Composites the $10 million Ansari X Prize in 2004 after three successful suborbital flights,” it said.

Launching directly into orbit from high altitude “will mean lower costs, greater safety, and more flexibility and

responsiveness than is possible today with ground-based systems,” the announcement said, adding that the capability of making quick turnarounds will “break the logjam of missions queued up for launch facilities and a chance at space.”

First will come unmanned payloads, with human flights to follow “after safety, reliability and operability are demonstrated,” the announcement said. —Dan Namowitz

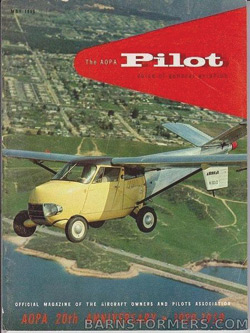

1954 Aerocar offered for $1.25 million

There are very few Aerocars left from the 1950s and 1960s, when inventor Molt Taylor hoped to put airplanes on the highway as well as in the air: One of them is for sale for $1.25 million.

Courtesy Aircraft in Rockford, Illinois, is brokering the sale of Aerocar N101D, most recently owned by Greg Herrick and on display at the Golden Wings Flying Museum at Anoka County/Blaine Airport, 10 miles north of Minneapolis. It is listed by the museum as part of the collection. The aircraft was serial number three and won a United States type certificate.

The one for sale has folding wings that are towed behind the car in transit on the road. It also features a horn and a rearview mirror. It is a two-place aircraft with a single Lycoming O-320 mounted over the rear wheels. It could be a noisy handful on the road and a handful in the air, as well. It wasn’t fast, couldn’t lift much weight, but won fame for successfully flying and driving.

Cessna adds inspections for aging aircraft

Cessna Aircraft Company will add inspection procedures to its service manuals for aircraft built between 1946 and 1986 to detect signs of problems common to aging aircraft. The inspections will focus primarily on signs of corrosion and airframe fatigue.

The supplemental inspection procedures affect 100- and 200-series aircraft. Inspections for the 200 series have already been added, while supplemental inspections for 100-series aircraft will be added in April 2012.

“The supplemental inspection program we’ve developed is primarily a visual process aimed at supporting the continued airworthiness of aging airframes,” said Beth Gamble, Cessna’s principal engineer for airframe structures. “Through this education effort, we hope to answer most questions before we release the revised service manuals. We encourage owners to check in with their local Cessna service affiliate at the appropriate times to have the mandatory inspections completed.”

The criteria for initial visual inspections will vary by model and aircraft age or hours of operation. Cessna authorized service providers will have special training and access to specific equipment for the inspections and for repairs, if required.

“Corrosion and fatigue are inevitable but with early detection and proper maintenance, severity and effects can be minimized,” Gamble said. “The new inspection requirements we’ve developed are very simple, and are based on visual inspection that can be done quickly by a trained inspector during an annual inspection.”

Czech Sport Aircraft offers lower-cost trainer

Flight schools are the targeted market for the SportCruiser Classic, a Czech-built Light Sport aircraft that is equipped with an analog instrument panel to bring the introductory price down to $119,500, including transportation and document charges. It is offered through U.S. Sport Aircraft in Fort Pierce, Florida.

Flight schools are the targeted market for the SportCruiser Classic, a Czech-built Light Sport aircraft that is equipped with an analog instrument panel to bring the introductory price down to $119,500, including transportation and document charges. It is offered through U.S. Sport Aircraft in Fort Pierce, Florida.

Other than a different paint scheme, it is identical to the SportCruiser, the flagship model that can reach prices of $150,000 to $160,000 with avionics options that include a glass cockpit.

Options available on the Classic model include an IFR training package for $6,000, and a $4,200 ballistic recovery parachute. The aircraft carries 30 gallons of fuel (29.6 useable).

The SportCruiser Classic is equipped with a traditional six-pack of instruments: attitude indicator, heading indicator, altimeter, airspeed indicator, rate-of-climb indicator, and turn-and-bank indicator. It has analog engine gauges. The avionics package includes a Garmin SL40, Garmin aera 500 GPS, Garmin GTX 327 transponder, and a PS Engineering PM 3000 intercom. Adjustable rudder pedals with toe brakes, electric pitch and aileron trim, and an ELT are standard equipment. Also standard is day and night VFR lighting.

Mike Goulian wins top airshow performer award

Airshow performer and past national aerobatic Unlimited Class champion Mike Goulian has won the airshow industry’s top award given for making the greatest contributions over the past year.

Airshow performer and past national aerobatic Unlimited Class champion Mike Goulian has won the airshow industry’s top award given for making the greatest contributions over the past year.

Goulian becomes only the seventh air- show professional to be awarded all three of the airshow industries’ top honors: the ICAS Sword of Excellence, Art Scholl Memorial Showmanship Award, and the Bill Barber Award for Showmanship.

Goulian, author and coauthor of two aerobatic training books, operates an FBO at Bedford, Massachusetts. He competed in the Red Bull race series worldwide before those races were put on hiatus for safety concerns. In addition to winning the Unlimited national aerobatic competition earlier in his career, he also won the Advanced national championship.

Off the tarmac, Goulian is known for his efforts to promote the airshow industry and improve airshow safety. He is known for being generous with his time not only with sponsors, but also with fans.

With him (second from left in the photo) when he received the award were his wife, Karin, and daughter, Emily.

Test Pilot By Barry Schiff

- Why is it a good idea to manually move the flight controls through their full range of motion before starting the engine?

- True or False: A turbojet-powered airplane with a true airspeed of 460 knots is flying through cumuloform clouds containing supercooled water droplets. Because the ambient (static) air temperature is -10 degrees Celsius, the pilot should anticipate structural icing.

- Which of the following is correct?

a. The Republic P–47 Thunderbolt was called “the jug” because its barrel-shaped fuselage reminded some of a jug.

b. It was called “the jug” because its radial engine had so many cylinders, or jugs. - What is the maximum deviation allowed for a general aviation compass on any given heading?

- From reader Willis Irons: What was the first municipal (city-owned) airport in the United States?

- A pilot wants to make a nonstop flight from the United States to Africa. The shortest such flight would depart from

a. Florida.

b. Hawaii.

c. Maine.

d. North Carolina. - Following massive bombardment, 35,000 U.S. and Canadian troops stormed ashore at Kiska in Alaska’s Aleutian Islands during World War II. Explain why only 21 troops were killed during this assault.

- An airplane has wings that are washed out. This means that

a. the bugs have been removed from the leading edges.

b. the wings’ angles of incidence have been reduced.

c. the wings’ angles of attack have been increased.

d. the wings are at least partially stalled.

1,000-hour goal is a lifetime achievement

1,000-hour goal is a lifetime achievement

Ninety-three-year-old Ike Kibbe wanted to end his flying career with 1,000 hours, so last year he took to the skies to make the dream come true. Starting with 965 hours, he hired instructor Sue Shambeau and began flying out of Martin State Airport at Baltimore. He landed at every airport within an hour’s flying time from Baltimore, including one—Clearview Airport in Maryland—that is located on a steep hill and has a runway less than 2,000 feet long. On September 17, he made his goal, logging his 1,000th hour on a flight from Baltimore to Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, where he once worked as a volunteer at the Piper Aviation Museum. He has been a pilot since 1940.

Record awarded to Maryland students

A record for human-powered helicopter flight has been certified by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale for two flights made by University of Maryland students and Judy Wexler, a lightweight but powerful bicyclist. The students, some of them now graduates, built a machine they dubbed Gamera and set world records earlier this year for flight duration and flight duration with a female pilot. The FAI certified the 4.2-second flight of May 12 and the 11.4-second flight of July 13, which now supersedes the first. Gamera was designed and built by a team of some 50 students at the university’s Clark School, and piloted by Wixler, a biology student. The team is currently working on a new vehicle in pursuit of the Sikorsky Prize. The new vehicle will be lighter and more efficient than the original. The team hopes to have it completed in early 2012.

French company flying luxury amphib

A French company named Lisa is developing a luxury Light Sport airplane that can land on water, snow, or runways. It’s named Akoya (uh COY ya) and carries two people. Its wings fold for storage on land or, the company says, it can fit onto the back of your yacht—if you happen to have one. It can go 680 miles on 18 gallons of gas and costs $411,000, but that includes pilot training for all three types of landings and three years of maintenance. Lisa expects to certify it to U.S. light sport standards in early 2012 and make the first deliveries by September 2012.

While it is powered by a 100-horsepower Rotax engine, there are plans for an all-electric version. Fuel cells burning hydrogen and oxygen, like those in the now-grounded space shuttle, will power an electric motor in cruise flight. For takeoff, solar cells on the wings will add extra power.

TEST PILOT ANSWERS

- Engine noise and vibration can mask problems (such as cable or pulley snagging and rasping) associated with the primary flight controls.

- False. At that airspeed, the air temperature immediately ahead of the aircraft is increased 30 degrees by compression. This results in a total air temperature of +20 degrees, which is too warm for structural icing to occur.

- Neither is correct. The P–47 was the largest and heaviest fighter ever powered by a single reciprocating engine and was regarded as a “juggernaut” or “jug.”

- 10 degrees. If using a particular piece of equipment on board the aircraft causes deviation in excess of 10 degrees, a warning placard must be conspicuously displayed in the cockpit.

- The Tucson Municipal Flying Field opened in 1919. It was four miles south of Tucson on the Nogales Highway, present location of the rodeo grounds. The city’s airport was moved in 1925 to what is now known as Davis-Monthan Air Force Base.

- c. If you don’t believe it, look at a globe of the Earth.

- There likely would have been many more casualties had the Japanese actually occupied the island as had been believed.

- b. Airplane designers wash out or twist some wings so that the tips have smaller angles of incidence than the inboard wing sections. This improves the stall characteristics of a wing by ensuring that inboard wing sections stall before the outboard sections do, thus improving lateral control and stability.