Pilot Briefing

News from the world of general aviation

Conrad Huffstutler heads Wild Warbirds in Uvalde, Texas, and was planning to restore the Wildcat behind him for the Sierra Industries collection, which includes the P–51 Mustang on the right. Instead, the Wildcat behind him will be sold as is since a second Wildcat is nearing completion.

Restless Wildcat waiting to fly again

Rescued after 48 years under Lake Michigan

By Alton K. Marsh

Ensign George L. Bevin walked out to his General Motors FM–2 Wildcat on the morning of December 19, 1944, with one goal in mind: qualify as a carrier pilot. His crew chief placed a shotgun shell loaded only with gunpowder in the engine of Bureau Number 55404, and it was fired electrically, pressurizing the start mechanism. Soon Bevin was on his way in formation from Chicago’s Naval Air Station Glenview to a paddle-wheel aircraft carrier splashing in Lake Michigan.

Bevin would have to land in 550 feet and catch a wire, but on this day he would take 551 feet and a bath in the lake. He escaped injury. The USS Wolverine, a converted passenger ship, had spent its night at Chicago’s Navy Pier, but was now 20 or more miles offshore. The water depth was 250 feet. Twenty-three knots of wind blew down the deck as he approached. It was normal and the signal “cut” was given. The accident card tells the rest: “He made a vicious hold-off, clearing all wires and barriers before the wheels touched the deck. He applied brakes at this point, but the airplane rolled off the bow into the water.” The airplane drifted down, miring upside down in the silt.

There were 140 warbirds that went into the lake for one reason or another. Many different models were involved.

In 1993 a 40-foot A&T Recovery boat positioned above 55404, its winches straining, pulled the aircraft out of the lake, still in good condition with its paint scheme preserved by the cold, deep water. The shotgun shell was still in the breech; a mechanic’s screwdriver was found wedged in the belly. Paint on metal blisters beneath each wing were still pockmarked by the cartridges expelled by the aircraft’s four .50 caliber machine guns. The throttle was still retarded; its R-1820-56 engine of 1,350 horsepower was frozen forever by rust and silt.

The Wildcat was raised with private money for the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida. The museum already had an example of a Wildcat, so 55404 was cannibalized for parts from the nose to complete the display aircraft. Then it was traded for a Sopwith Camel fighter biplane to an owner in California until someone driving by spotted it. It ended up at Wild Warbirds in Uvalde, Texas, and is owned by Sierra Industries, a jet refurbishing firm. There, it faced the same fate as the one at the National Naval Aviation Museum. There was a prettier Wildcat already present. It would be the one finished and flown by Wild Warbirds chief Conrad Huffstutler. There wasn’t room for 55404, and at this writing it was on the block again, waiting to be sold. If the new owner wishes, it can be restored by Wild Warbirds.

Email [email protected].

Airplane’s a star in ‘The Dog Stars’

Outdoors activist flies into fiction

By Sylvia Horne

Author and environmental IST Peter Heller is a man who goes to extremes. He’s an accomplished whitewater and expedition kayaker and conquered the rapids in the Pamir Mountains and the Tien Shan Mountains in central Asia, as well as the Tsangpo Gorge in eastern Tibet.

When he decided to learn to surf, he surfed from California down the coast of Mexico in a single year. He documented his adventures in several non-fiction books and articles for National Geographic Adventure, Outside, and Men’s Journal magazines.

On a fishing trip several years ago, Heller was a passenger in a small airplane flying into a backcountry strip at Schafer Meadows, Montana—he decided he needed to learn to fly. He wanted to learn to fly bush planes into backcountry strips in the shortest time possible. After 20 days and 40 hours of private instruction from renowned mountain pilot Dave Hoerner he got his private pilot certificate in Kalispell, Montana.

“It’s the way I do stuff,” he says. “I compare it to drinking from a fire hose.” With 179 hours under his belt he considers himself a low-time pilot, but an enthusiastic one. “I love flying,” he says. “I always marvel at how the world perfects itself when you look down at it from altitude. How you detect patterns, how creeks turn into rivers, how countryside transitions to cityscape. Even a junkyard can look appealing from above.”

Heller manifested his passion for aviation in his first novel, The Dog Stars. He tells the story of a lone survivor of a global flu epidemic who flies his Cessna 182 around the perimeter of the airport to scan for intruders—until one day he receives a broken radio transmission and sets out in his airplane and with limited fuel reserves to find the source.

The star in the novel is the aircraft, modeled on Heller’s own 1956 Cessna 182—down to the tail number. The story revolves around Erie, Colorado, where the airplane is also based in real life. He describes in detail short-field, soft-field landings and takeoffs, and for a desperate escape has the main character, Hig, cutting down trees and filling in holes on an improvised landing strip, as well as solving complex weight-and-balance issues—including a cargo of weapons, people and lambs. His calculations are unforgiving and he eventually has to leave one passenger behind. “I know pilots are an exacting bunch. I’ve had those calculations checked by two high-time pilots with experience in backcountry flying,” he laughs.

Heller flies his Cessna 182, lovingly called the Beast, for the pure joy of it. “All my interests complement each other. There’s not one activity I prefer over the other, except that in flying there’s less margin for error. You don’t really get a second chance when you get something wrong.”

Email [email protected].

Piper Fly-In to commemorate anniversary

Join the Piper Aircraft Co. as it celebrates its seventy-fifth anniversary in Vero Beach, Florida, November 9 through 11. Planned events include pancake breakfasts, facility tours, an exhibit hall, and aircraft display. A history of Piper aircraft will be presented by Roger Peperell on Saturday, November 10. Details of the event, including flight times and arrivals, were still under review at presstime.

Sikorsky prize may take another year

The team trying the hardest, and with the greatest success so far, to win the $250,000 Sikorsky prize for a human-powered helicopter is at the University of Maryland’s James Clark School of Engineering. The faculty-led team got its 114-foot monster, Gamera II, past nine feet and flew for a minute in a separate flight. It crashed twice before students had to return to classes and rethink the design. The first contender to reach 9.8 feet during a one-minute hover while remaining centered in an 11.7-foot area wins. A team in Toronto called AeroVelo, a mix of students and professionals, has flown 14 seconds with a similar vehicle built around a $10,000 bike, but seems about a year behind Maryland.

—Alton K. Marsh

Test Pilot By Barry Schiff

- From reader Tom Nagorski: What famed World War II pilot was designated as "fit for full flying service" and became an ace while simultaneously receiving military medical compensation for being 100-percent disabled?

- True or False? It is possible to fly any light plane such that it cannot be made to stall at any airspeed.

- True or False: Transponders should not be in the On or Altitude position while taxiing to the run-up area.

- Mix and match the following:

1) sunset to sunrise

2) end of evening twilight to beginning of morning twilight

3) one hour after sunset to one hour before sunrise

a) may log nighttime

b) position lights required

c) three takeoffs and landings needed for currency - From reader Dan Stroud: What is the aeronautical connection between President George H.W. Bush and actor Paul Newman?

- True or False? Hurricanes and typhoons are meteorologically identical.

- From reader John Schmidt: Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins could not obtain life insurance prior to their lunar flight in Apollo 11. How did they ensure that their families would be financially secure in the event that they did not return?

- Why do pilots refer to anti-aircraft fire as flak?

Brightline Bags Flex System

You asked for choices, you got them

By Ian J. Twombly

There are two schools of thought when it comes to product design. One is to create a product the market didn’t even know it needed that’s easy to use and fits perfectly into people’s lives. The iPod is a great example. The other philosophy is to give customers what they ask for, which Brightline Bags has done with gusto.

There are two schools of thought when it comes to product design. One is to create a product the market didn’t even know it needed that’s easy to use and fits perfectly into people’s lives. The iPod is a great example. The other philosophy is to give customers what they ask for, which Brightline Bags has done with gusto.

At first glance, the Flex System is the most complicated flight bag one could ever imagine, although “bag” in this case is relative. The Flex System is more of a catalog of bag options, each with a unique size, shape, and purpose. Spend some time playing with the system, however, and the thing starts to make sense.

There are 11 different pieces in all, each more or less interchangeable with each other. It would take a doctorate in physics to understand all the various combinations. Thankfully Brightline has done much of the hard work for us and created five preconfigured bags of various sizes. If you want more than five options you go to work picking a center section, end caps, and side pockets. That exercise will get you everything from a cool (in a pilot nerd sort of way) briefcase to a large overnight suitcase.

The new features are too numerous to name, but let’s just say that a lot of thought went into the system, and as a result the features are very impressive. Each bag is slightly bigger than the previous Brightline offering, meaning it can fit a laptop easily, not to mention an iPad or two. The side pockets come and go easily, and the scalability of the system allows you to keep everything packed and just add on or take off sections depending on your needs.

Price: $12 to $265 per piece

Contact: www.brightlinebags.com; 417-721-7825

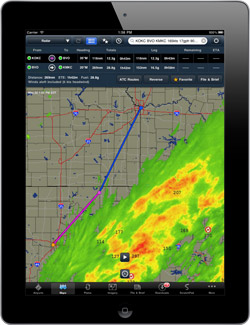

New from ForeFlight

Electronic Flight Bag software maker ForeFlight recently introduced a runway incursion avoidance feature as part of its expanding package of Advisor features.

Electronic Flight Bag software maker ForeFlight recently introduced a runway incursion avoidance feature as part of its expanding package of Advisor features.

Now when a pilot uses the app while taxiing on an airport, a large box will pop up and warn him of an impending runway crossing. Another box pops up when the pilot has entered the runway environment. There also are aural alerts that can be sent to a headset that meets a certain Bluetooth protocol. Currently only Lightspeed’s Zulu.2 (www.lightspeedaviation.com) meets the standard. Headsets with an auxiliary jack can be connected to the iPad and receive the alerts as well.

The technology, which was developed by the MITRE Corporation (www.mitre.org) and fine-tuned by ForeFlight, works by establishing a set “box” around the runway and bringing up the alert when the pilot gets close and within it. Certain larger airports with more complicated layouts were manually altered to get a more precise and correct alert.

The latest edition of ForeFlight also includes X-Plane support. This feature enables X-Plane users to use ForeFlight on the ground, enhancing the simulation experience and making it easier to learn the app’s features.

Both the new Runway Proximity Advisor and X-Plane support are available now for download in Apple’s App Store as part of any ForeFlight subscription level.

Milestones: Returning to the scene

Still feeling the ripples of an event 50 years ago

By Leroy Cook

There’s a taxiway at Lawrence Municipal Airport in Kansas that may look a little timeworn, compared to the nice new concrete runway paralleling it. As I turned onto the taxiway after my landing roll there was a hint of flashback in my mind. Involuntarily, my eyes were drawn to the buildings on the west field boundary, rather than the shiny new terminal and FBO hangar just ahead.

It was over there, exactly 50 years ago, that I met with FAA Inspector W.A. Murphy Jr. to report for my private pilot checkride. At that time, this little taxiway was actually part of Runway 1/19. As I recall, it was the only pavement on the field other than the ramp; a 20-foot-wide gravel taxiway provided access to it, and an east/west turf crosswind runway served the predominant conventional-gear (tailwheel) airplanes of the day.

My little tricycle-gear Cessna 150, on the other hand, was brand new at the time, fully equipped with a 90-channel King transceiver in addition to the crank-tuned VHT-3 Narco Superhomer nav/com radio. I was proud to be one of the school’s first students to upgrade from the Cessna 140, which had carried only a four-channel Narco and a GE low-frequency receiver. I was also the proud possessor of four hours of instrument dual, some of which was acquired with the venturi-driven World War II-surplus gyro horizon and compass in the 150, instead of the 140’s turn-and-bank indicator. Oh, I felt more than ready, 50 years ago, with 51 hours and 30 minutes in my logbook.

This day, I am on a mission to train a would-be student in the art of cross-country flying, a task that has led us, exactly a half-century after the fact, to the same bit of pavement where I earned my own set of wings. We park on a broad ramp in front of the shiny, welcoming terminal building, with its chilled interior and soft seats. It’s a far grander structure than was provided by Erhart Flying Service in 1961. Air conditioning wasn’t common, so FAA inspectors needed to doff their jackets when conducting summer checkrides in the field.

The FAA was only three years old at the time, recently descended from the Civil Aeronautics Authority. It began as a full-fledged Federal Aviation Agency before it was submerged into a yet-to-be-created Department of Transportation, where it was demoted to an administration. The FAA’s charter then called for the “promotion of aviation” in addition to safety oversight. To meet this mandate, the agency provided routine field service to the industry from its district offices, its inspectors roaming the territory to give checkrides, written tests, certificate inspections, and free advice. They even flew little airplanes on their rounds in those days, and they knew airport operators by name.

I had taken my knowledge test, 50 multiple-choice questions, while on a solo cross-country to the airport housing the General Aviation District Office (FAA offices were logically located on airports back then), and I received my passing grade slip in the mail after an anxious two-week wait. The idea of having to pay to take a written test would have been considered absurd, even if it could have resulted in obtaining immediate results. Inspector Murphy conducted my practical exam for free, as part of his job. I was one of a half dozen or so applicants on the day’s agenda, and he and his crew had a busy day ahead. Thanks to the $2 per hour I had been paying my instructor for dual, I was well prepared; I repeated all the things I’d been told and shown, which seemed to be enough to satisfy Murphy. He was amused that I plotted my cross-country course with a wooden ruler and a protractor, outlining the data for the proposed trip on a Big Chief paper tablet. I also produced an acceptable wind triangle on the pad; I couldn’t afford an E6B computer, which cost as much as an hour of airplane time, but I did have an Army-surplus D-3 time/distance computer to use for my in-flight calculations.

FAA inspectors of 50 years ago were highly experienced pilots, often wartime veterans, with readily supplied opinions. Their word was law, and we were cautioned to remain attentive and agreeable during a checkride. Bureaucracy and political correctness were given short shrift. I was reminded to stick precisely to the runway’s centerline, and to maintain proper control position during taxi. Inspectors, unlike designated examiners, had no interest in establishing a rapport; they were not likely to see you again, even for a retest, and their only focus was on assuring that you met the criteria laid down by the standards.

Spin demonstrations had been deleted a few years earlier, but stalls were taken seriously, and I had become thoroughly proficient in snapping the stick forward and recovering straight ahead. Landings were expected to be similar to those of a tailwheel airplane, nose-high and at minimum speed, executed from a tight, power-off approach. Reapplying power, once it had been removed, was a sign of vacillating judgment during a landing approach. As in forced-landing demonstrations, one was expected to fly to the runway power-off. A slip to lose altitude was a normal maneuver.

Once I had satisfied the oral and flying criteria, Inspector Murphy wrote up my temporary private certificate and offered a modicum of congratulation, anxious to be on his way, back to the district office. I noted my total investment in my logbook; $597.15, about a third of year’s wages.

Some 34 months later, Inspector Murphy and I met again, for the commercial checkride, after I had matured with Army service and 212 hours. He didn’t remember me, but I passed after a discussion of my deficient lazy-eight technique.

As the years went on, I had checkrides for instructor, instrument, multiengine, and other ratings, most with FAA inspectors, and I adapted to paved runways, improved avionics, and ever-more-complex aircraft systems. The old Lawrence airport now boasts a 5,700-foot-long, 100-foot-wide runway with an ILS approach, and nearby Class B Airspace, but I can still pick out details from my private pilot checkride, such as the taxiway. And the sky remains open and beckoning, just as it did 50 years ago.

Leroy Cook is a frequent contributor to Flight Training magazine.

Teen restores prize-winning airplane

By Alton K. Marsh

Seventeen-year-old Dillon Barron loves airplanes, so it is fortunate he lives next to the family’s private grass strip in Missouri where his father, Michael, and grandfather, John, both airline pilots, restore Cessna 195s. Michael, who manages nearby Hannibal Regional Airport, found a derelict 1954 Cessna 170B that was in danger of eviction for vagrancy and offered it to Dillon as a learning project.

Dillon learned so much that the airplane won Reserve Grand Champion in the Classic category at EAA AirVenture 2012. What started out as a quick paint job and an engine overhaul became a detailed restoration to factory new condition after factory paint and fabric were discovered during the teardown. It cost $7,000 as it sat and required a $25,000 restoration. It could easily sell for twice that much.

Dillon finished his private pilot certificate in August 2012, but had 150 hours at the time. Some of those hours came from all the airplanes he soloed on his sixteenth birthday. Here’s the list: A Cessna 170B, three Cessna 195 airplanes including one used for rescue in Alaska with a 330-horsepower Jacobs radial engine, two Beech 18 multiengine airplanes (one a military version), and a North American AT–6 trainer. Barron Aviation also restores Beech 18 and AT–6 aircraft. Michael and John train future pilots in a 1955 Cessna 170 and a 1956 Cessna 172, and tow glider rides they offer to the public with a 1956 Cessna 172.

Dillon wants to stay around small airplanes—especially those needing restoration. He would like to fly warbirds but also do bush flying Alaskan style—although corporate flying would work as well, and airlines are not out of the question. Got that?

The horse that loved aviation—especially balloons

By Alton K. Marsh

Sammi’s day job was to practice for dressage performances, memorizing routines along with his rider. But the horse’s free time was his own, and he devoted it to his love of aviation. He got an airplane ride in his youth and developed a passion for flying.

He was born in Germany but flew to the United States as a two-year-old to begin training. After schooling he ended up in Peterborough, Ontario. Sammi lived near a small, rural airport.

“This horse looked up and watched every aircraft, but especially loved the hot-air balloons that pass over our location from time to time—becoming extremely upset when ‘his’ balloon disappeared behind the trees,” said trainer Suzanne Ramsey-Falquier.

Sammi tried to get as close as possible, tracking the balloon’s direction. When it disappeared, he would race up and down the fence, stopping abruptly, looking up, and calling. The pilots probably thought his whinny was part of their bucolic experience, but they were instead part of Sammi’s experience.

Last year Sammi had a minor medical problem that turned into something major, and he didn’t survive, robbing him of a chance to compete in the 2015 Pan American Games in Toronto. But his love of aviation lives on in the memories of all who knew him.

- Cost of an airline ticket for a horse from Germany to the U.S.: $5,248 on Lufthansa

- Number of horses carried by Lufthansa per year: 2,000

- Number of horses with pilot certificates: zero

FAA to scrutinize light sport aircraft in March

Starting in March 2013 the FAA will send inspectors to all light sport aircraft (LSA) manufacturers, starting with those releasing new models. Practice inspections were conducted at a few manufacturers in 2012. The inspections follow a report by the FAA saying not all manufacturers are good at paperwork needed to confirm that industry-agreed-upon standards have been met. LSA makers self-certify that they have met standards, with the FAA checking the paperwork.

Test Pilot Answers

- Royal Air Force pilot Douglas Bader lost both legs in an aerobatic accident in 1931. Mastering prosthetic legs, he regained flying status in 1939, flew Hurricanes and Spitfires, and fought in the Battle of Britain. He was shot down over France in August 1941, and taken prisoner. He attempted escape so often that his German captors threatened to remove his legs. Read Bader’s inspiring story in Paul Brickhill’s book, Reach for the Sky.

- True. Just as stall speed increases with increased G loading, it decreases with decreased G loading. At zero Gs, an airplane has no stalling speed and cannot be made to stall.

- False. Turning on transponders ensures that aircraft are visible to ATC surveillance systems. (Refer to AIM 4-1-20a.)

- 1b, 2a, 3c

- Both were crewmembers on Grumman Avenger torpedo bombers during World War II. Bush was a pilot and Newman a radioman/gunner.

- True. The only difference between them is location. Tropical cyclones in the Western Hemisphere are called hurricanes. Those west of the International Date Line are called typhoons.

- The astronauts autographed hundreds of envelopes emblazoned with space-related images. Now known as "Apollo Insurance Covers" and valued at more than $5,000 each, these were stamped, mailed by a friend, and postmarked on the day of departure, July 16, 1969.

- Flak is an acronym that comes from the German word Fliegerabwehrkanone, which means "anti-aircraft cannon fire."