Avionics: When all else fails

An app that helps you glide to safety

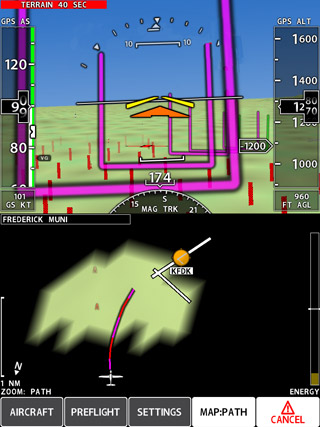

This iPad screen shot shows Xavion’s desired flight path to the nearest runway. The airplane is flying at 99 KIAS, descending 1,200 fpm, and slightly low.

This iPad screen shot shows Xavion’s desired flight path to the nearest runway. The airplane is flying at 99 KIAS, descending 1,200 fpm, and slightly low.

Those of us who fly single-engine, single-pilot IFR may not like to dwell on these scenarios, but what are our odds of gliding to a safe landing at an airport if we lose the engine in instrument meteorological conditions? And how well prepared are we to deal with a total electrical failure in the clouds, or at night? Xavion is an iPad app that provides answers to the questions pilots constantly ask themselves in flight: What would I do right now if the engine quit? Or if the instrument panel suddenly went dark?

Designed by Austin Meyer, founder of the wildly successful X-Plane flight simulation software, Xavion uses the iPad’s internal sensors (or a Levil Technologies attitude heading reference system) to show pilots how to glide to a runway if the engine quits. It also provides an extremely capable substitute for traditional avionics if any, or all, flight instruments were to fail.

The Xavion display on a vertically mounted iPad shows a conventional EFIS representation with flight instruments (including a flight director) and GPS-derived synthetic vision, and a moving map on the bottom. A detailed setup procedure, and a short preflight weight and balance update, lets Xavion know or calculate the airplane’s best-glide speed, glide ratio, center of gravity, stall speeds, and other metrics so that the software can crunch numbers in flight to optimize guidance.

Xavion is extremely helpful for pilot situational awareness when everything is going smoothly. But in an emergency, a pilot can press the red Fly Hoops key and Xavion draws a three-dimensional highway-in-the-sky course that leads to a runway threshold within gliding distance. (And if no runway is within gliding distance, the pilot gets that news right away so he or she can devote his or her attention to an off-airport landing.)

Xavion doesn’t simply build solutions around the airplane’s best-glide performance. Its guidance offers somewhat steeper approaches that can be made at higher speeds and allows pilots to use landing gear, flaps, propeller pitch, and other tools to manage the airplane’s speed and descent rate. Also, Xavion shows the airplane’s “energy available” continuously so pilots can speed up or slow down to maintain the desired value.

One important limitation is that when using internal sensors, Xavion only knows the airplane’s GPS-derived groundspeed, not indicated airspeed, so pilots must be mindful of winds.

But can any iPad app really help pilots in such extreme circumstances?

To find out, I completely blacked out the rear-seat portion of an RV–4 canopy with tape and opaque plastic materials, placed an iPad II running Xavion in front of the rear-seat pilot, and recruited a pair of instrument-current general aviation fliers to serve as guinea pigs in that darkened chamber. In two successive flights and six simulated power-off approaches, I’d climb above 3,500 agl, reduce engine power to idle, and hand over the aircraft controls. The rear-seat pilot would press the emergency Fly Hoops key and follow the Xavion guidance to the nearest runway.

Even though neither of the pilots, Luz Beattie and Chris Lawler, had previously flown an RV–4, Xavion allowed them to control pitch, bank, and attitude with precision and get to a runway threshold in position to make a safe landing.

“It’s not enough to maintain best glide and fly in a straight line towards the nearest airport,” Meyer said. “Xavion takes you to the runway endpoints in a way that allows you to manage your airplane’s energy so that you arrive in position to land safely.”

Still, there are no guarantees. On Beattie’s second simulated power-off approach, she had to contend with a 30-knot tailwind at 3,000 feet agl, and the airplane got uncomfortably slow as the Xavion flight director commanded a pitch up because it wrongly concluded the airplane was far above its 74-knot best-glide speed. When I noted the airspeed was getting slow (the RV–4 has no audible stall warning), Beattie reduced the angle of attack and the rest of the approach went smoothly. Meyer said he plans to use ADS-B weather to incorporate wind information in future Xavion versions.

Beattie flew using the iPad’s internal sensors only, and she noted the flight director was “jumpy” at times and tricky to follow.

The next series of approaches with Lawler incorporated a Levil AHRS to enhance pitch and roll information, and he said the flight director was mostly smooth and stable. Lawler’s first approach (also with a strong tailwind during descent) was high but would have been salvageable with an aggressive slip. The second was a thing of beauty flown to 100 feet agl and directly over the runway centerline. On the third, Xavion erroneously warned throughout the approach that the runway was too distant to reach, but Lawler got there with altitude to spare by flying near the airplane’s best-glide speed (and possibly catching a tailwind).

Meyer said he’s considering altering Xavion so that, if a runway becomes reachable, the warning disappears.

In sum, the $99 Xavion app is an impressive piece of safety equipment that could be a lifesaver in an actual engine and/or avionics failure. It vastly enhances pilot situational awareness by constantly showing airports within gliding range at a glance, and its terrain database and GPS-derived synthetic vision depict mountains, rivers, roads, and valleys in colorful detail.

The iPad’s internal sensors do a surprisingly good job of staying oriented during normal flight, although they can be confused, at least momentarily, by uncoordinated flight and unusual attitudes. When linked to the Levil AHRS, however, Xavion precisely matches aircraft pitch and bank. (Also, the Levil AHRS can be linked to the aircraft pitot/static system to provide indicated airspeed and barometric altitude).

Xavion’s glass-panel representation will seem quite familiar to pilots accustomed to modern avionics, but steam-gauge pilots could find the transition jarring, particularly during an actual aircraft emergency. Like everything else, realistic practice enhances performance. (And in this case, pilots can practice on home computers using X-plane.)

Xavion and its $50 little brother X-vision (which shows the EFIS representation without the engine-out guidance) can be displayed on the iPad, iPad mini, and iPhone, but not Android devices; Meyer plans to produce the apps for Apple products only.

Meyer also is working with Vertical Power on the VP-400, an automated system designed to allow digital autopilots to fly coupled approaches to runway thresholds at the push of a button (see “Avionics: Runway Seeker,” August 2012 AOPA Pilot).

From my unobstructed front-seat perch in the RV–4, each of the simulated power-off approaches flown by Beattie and Lawler looked high—particularly those made to long runways. Meyer said that impression is nearly universal for two reasons: First, idle power produces some residual thrust and approaches are significantly shallower than actual engine-out glides.

Also, pilots are taught to touch down on the first one-third of any runway surface regardless of how much distance they actually need to stop, and Xavion makes a different calculation—it directs pilots to the place on the runway that maximizes the safety margin. For an airplane such as an RV–4, which typically uses about 1,000 feet of runway on landing, Xavion’s aiming point is 500 feet short of the middle of the runway (or 2,000 feet down a 5,000-foot runway).

“We try to center the rollout so that you have the same amount of runway in front of you as behind you,” Meyer said. “It’s a concept pilots aren’t taught and don’t train for. But the computer can visualize and enhance a pilot’s ability to find that point.”

Portable ADS-B traffic

SkyVision Xtreme lets you take it with you

A common refrain among pilots fortunate enough to fly with traffic warning systems is that they suddenly feel vulnerable in aircraft without them. Now, with SkyVision Xtreme, pilots can bring their traffic systems with them. SkyVision is a portable, self-contained ADS-B In system that provides a full traffic picture showing aircraft equipped with transponders, as well as ADS-B equipment. It’s an uncertified system designed for aircraft renters and pilots who fly multiple aircraft, and its components are upgradeable in the future as a permanent, installed solution that can comply with the FAA’s coming mandate.

This iPad screen shot shows all airborne traffic including headings, altitudes, and airspeeds. Aircraft with ADS-B Out (such as the DHL jet) also show flight numbers.

This iPad screen shot shows all airborne traffic including headings, altitudes, and airspeeds. Aircraft with ADS-B Out (such as the DHL jet) also show flight numbers.

I recently flew with a SkyVision portable unit at AOPA’s home base in Frederick, Maryland, and the hour-long flight showed the system’s promise—and the capabilities we can expect in 2020 and beyond when ADS-B will be required nationwide. SkyVision ($3,595) also shows subscription-free ADS-B weather.

SkyVision comes in a rugged, 7-pound plastic case. The box is sturdy and substantial to protect the electronics inside: a Navworx universal access transceiver (UAT), Wi-Fi station, and internal battery. Three external cables connect these components to a GPS antenna, power cord, and UAT antenna. I strapped the box in the rear seat of my Vans RV–4, attached the UAT antenna to the canopy with a suction cup, placed the GPS antenna where it had a good view of the sky, and plugged in the power cord (and audio cable).

After starting the engine, I turned on my iPad and launched the SkyVision app, which quickly connected to the WiFi station in the rear seat. Then I flew in the busy airspace between Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, Maryland, in search of aerial targets, and there were many of them. Airliners on approach to Dulles International Airport formed a long line at about 8,000 feet as they descended heading south; others flew east at about 7,000 feet on their way to Baltimore-Washington International Airport. A trio of general aviation trainers practiced ground reference maneuvers at much lower altitudes just north of the Potomac River.

All were plainly visible on the iPad long before I could see them through the canopy. An icon showing an airliner or light GA aircraft provided a strong hint about the type, and detailed data about each one told its relative distance, height above or below, heading, groundspeed, and whether it was climbing or descending.

SkyVision collects the information by pinging ADS-B ground stations and receiving information from them about nearby aircraft, regardless of whether those aircraft are carrying transponders or transmitting ADS-B Out signals. (Aircraft with ADS-B Out show even more information, such as N numbers or airline flight codes.)

SkyVision has a battery backup so that it won’t shut down in flight if a power source (typically a cigarette-lighter adaptor) becomes disconnected, or there’s a pause in electric current. If a connection is lost, a big red X covers the iPad screen, and an automated voice chimes in to alert the pilot.

My RV–4 is equipped with a Traffic Information System (TIS) that operates through a Mode S transponder and displays on a Garmin 696, and comparing the two traffic systems highlighted their differences. SkyVision’s main advantage is that it shows traffic all the way to the ground at my home airport, because there’s an ADS-B station on the field. Airplanes in and near the airport traffic pattern appear prominently, and it’s good to know they’re there since most midair collisions take place on VFR days near airports. (At Frederick, TIS typically cuts out about 1,200 feet agl because transponders lose signal coverage at that altitude.)

One aspect of the TIS system that I like, however, is the good job it does of prioritizing threats. It shows fewer of them, but those that appear on the screen tend to be relevant. SkyVision shows you the entire traffic picture, including distant airplanes that are highly unlikely to affect your flight path. Also, the SkyVision airplane symbols appear absolutely huge in proportion to their actual size, so the system gives a somewhat skewed impression that the air in all directions is densely packed with aluminum. (SkyVision lets you customize the settings to cut down the clutter.)

The SkyVision display can be viewed in a top-down, two-dimensional plan view; as seen looking forward through the windscreen in three dimensions; or both, in a split-screen orientation. It can be displayed on a broad array of Apple and Android devices and fit in just about any GA cockpit. The box can be stowed and the antenna wires routed unobtrusively.

SkyVision’s founders have been designing ADS-B systems for GA aircraft since 2009 and this concept for a portable ADS-B system that is both useful now

and can comply with the FAA mandate in the future has great promise for ferry pilots, flight instructors, renters, or just about any pilot who flies more than one airplane.

Email [email protected].