Glacier glory

Pilots get unique perspective of Glacier National Park’s size, beauty

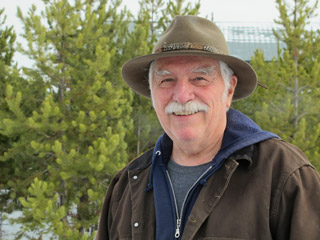

Gerry Hurst, an 11-year Cabin Creek Landing resident, enjoys spotting wildlife in the northwestern Montana wilderness from his beefed-up Cessna 150.

Gerry Hurst, an 11-year Cabin Creek Landing resident, enjoys spotting wildlife in the northwestern Montana wilderness from his beefed-up Cessna 150.

A lone wolf lurks in brush atop an open ridge stalking an unsuspecting herd of elk below, but its predatory desires are thwarted when Gerry Hurst flies overhead in his Cessna 150 fitted with a 160-horsepower engine, beefier nose gear, and oversize tires for backcountry flying. Spooked, the wolf bolts from its hiding spot; the elk pay no attention. It’s the latest wildlife-spotting tale Hurst shares of flying over Montana’s Northern Rocky Mountains. That and sightings of bull moose and grizzlies, and clearing moose, deer, and other animals from the Cabin Creek Landing residential airpark runway with a low pass. At the private field in Marion, Mont., pilots talk more about using aircraft to admire the area’s diverse animal species and scenic beauty from the air, less about the aircraft themselves.

“Wait till you see Glacier from the air,” Hurst tells an East Coast pilot preparing for a flight in a converted Piper Tri-Pacer with his airpark neighbor, Chet Todd. “It’s spectacular!”

Hurst’s comment seems an understatement as Glacier National Park’s towering peaks come into view still 30 nautical miles away.

On this clear, calm winter day, it’s as if Todd and his passenger are the only two taking in the wonders of the country’s tenth national park, which spans more than a million acres. Overflying Glacier National Park gives pilots “a great perspective of the size of the park and the beauty,” Todd said. With all but about a 10-mile stretch of Glacier National Park’s popular Going-to-the-Sun Road closed during the winter, the majesty of the park is largely limited to those who backcountry ski or snowshoe. Not so for pilots. Unlike the Grand Canyon, Glacier National Park has no special flight rules; however, within the boundary of the charted National Park Service area pilots are requested to fly at least 2,000 feet agl.

Chet Todd fuels a converted Piper Tri-Pacer.

Chet Todd fuels a converted Piper Tri-Pacer.

Todd, manager of the Cabin Creek Landing Bed and Breakfast at the Cabin Creek Landing fly-in community flies at 9,000 feet msl beside the lower ridges (only six peaks top 10,000 feet msl in the park). He points out popular sites near the entrance of the park, including backcountry strip Ryan Field and Whitefish Lake and Mountain Resort. Beside the rugged, snow-covered mountains, the Tri-Pacer feels like a tiny model replica. Below, Lake McDonald—Glacier’s largest lake at nearly 10 miles long—is shrouded by a blanket of fog.

Lure of the mountains

Protected since President William Howard Taft signed legislation in 1910 establishing the land as a national park, Glacier National Park now draws more than one million tourists to the area annually. The mountains kept Hurst and Todd’s family returning for more—eventually wooing them to settle in the area.

Hurst had vacationed in northwestern Montana and jumped at an opportunity to relocate to work in Kalispell near the park. He based his airplane at the city’s airport, but he and his wife longed to live at a residential airport. They were the first to move into Cabin Creek Landing 11 years ago when it opened.

Todd, a fourth generation pilot and California native, grew up flying over the area with his family each summer. His father, Rick Todd, introduced him to the beauty of flying near Marion, Kalispell, and Glacier, just as his father had done for him. “It’s the most beautiful part of the country,” Rick Todd said. “That’s how my dad found it.” Chet Todd’s grandfather and grandmother brought the family to Marion during the summers, staying in a ranch house with a grass landing strip outside. Rick Todd, and later Chet Todd and his brothers, grew up fishing in Marion’s Little Bitterroot Lake, hiking in the wilderness. Chet Todd’s parents purchased seven acres at the Cabin Creek Landing fly-in community, just a couple miles from the ranch house, with the intent to build a bed and breakfast. Chet Todd felt a pull to return to the area with his wife, Corynne. The newlyweds moved from California to Montana to run the bed and breakfast in 2011; now, Rick Todd and his wife also live at the airpark.

Living in the shadow of Glacier

Tie downs and fuel are located just in front of the Cabin Creek Landing Bed and Breakfast’s Old Montana-style lodge.

Tie downs and fuel are located just in front of the Cabin Creek Landing Bed and Breakfast’s Old Montana-style lodge.

About a half-dozen families call Cabin Creek Landing residential airpark home, but pilots can get a taste of the life by flying in and staying at Cabin Creek Landing Bed and Breakfast. The two-story, Old Montana-style lodge was built with pilots in mind, Rick said. Situated on seven acres that face the runway, pilots can get fuel and taxi up to the tiedown area right in front of the bed and breakfast; three of the six rooms in the cabin face the runway and tiedown area so pilots can keep an eye on their aircraft if they choose. The 3,400-foot Runway 02/20 is paved and has pilot-controlled lighting; a mechanic also is available on the field. The bed and breakfast offers a courtesy car for those who fly in to explore the area.

Todd and other airpark residents openly share tips for backcountry airports near Glacier National Park, Great Bear Wilderness, and the Bob Marshall Wilderness. “The flying up here is unbelievable,” Todd said.

Pilots fly just feet above the treetops on approach to Cabin Creek Landing’s Runway 20.

Pilots fly just feet above the treetops on approach to Cabin Creek Landing’s Runway 20.

As for flying into Cabin Creek Landing, the winds normally favor Runway 20, which requires an approach over a mountain. For pilots who aren’t proficient in backcountry flying, the approach may be nerve-wracking. The downwind leg parallels a nearby mountain ridge, forcing pilots to fly a tight pattern; the base leg points directly at another nearby mountain; and final approach is made just a few feet above the treetops before the mountain gives way to the runway. With this approach, there’s little room for error. In case of an emergency, U.S. Highway 2 parallels the runway, making a safe landing spot, Rick explains.

Even though Hurst typically keeps the snow plowed from runway in the winter, the Todds suggest calling in advance just to double check. Even with Hurst’s efforts to clear the runway, pilots still might need to do a low pass to ensure it’s free of moose or elk.