Technique: The third wheel

Back to basic stick-and-rudder skills with a tailwheel endorsement

For such a tiny part of the airplane, the third wheel of a taildragger has a vicious bite if it’s not treated with proper respect. “You can’t get lazy in a tailwheel,” instructor Ron Rapp explained early in 5G Aviation’s tailwheel endorsement training program at Southern California’s John Wayne Airport-Orange County. Pilots who become complacent and touch down misaligned with the runway in a tricycle-gear airplane may bounce or skid, but the poor form won’t likely lead to an incident or accident. Not so in a “conventional-gear” aircraft: A precise level of stick-and-rudder skills is necessary “to keep the airplane in one piece,” Rapp said.

To illustrate his point, Rapp demonstrates slow-speed ground loops to his tailwheel transition students using a Super Decathlon so they can understand how the turn tightens leading to a ground loop, the rudders lose effectiveness, and the aircraft can be damaged. In the low-speed ground loop to the left, applying full right rudder—even brakes—during the turn yielded no results. If the Decathlon were going any faster, “the wing would tip and hit the ground,” Rapp said, “and you’d end up with an expensive repair bill.”

Forward, please. Tailwheel aircraft are naturally unstable on the ground because the center of gravity is located aft of the main landing gear. Ever tried to push a tricycle backward? With the slightest turn, the tricycle wants to veer to one side or the other—or spin. That’s how a taildragger behaves moving forward.

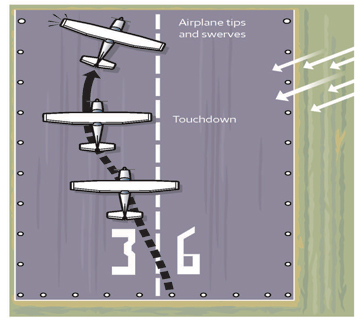

“The important thing with the tailwheel is that you have to keep the nose straight, so the airplane has to be pointed in the same direction that it’s going,” Rapp explained. “Anytime a divergence starts to develop between those two things, you’re going to see that ground-looping tendency.” The key to correct drifting off center on the taxiway or runway without ground looping is to stop the drift before bringing the aircraft back to the desired position. Holding the rudder too long or swerving could set up a ground loop.

To help pilots learn the coordination of power, rudder, and brake—and understand how tailwheel aircraft want to tighten a turn as it progresses—Rapp uses zigzag and figure-eight taxi drills. Two critical considerations while taxiing are keeping the stick back so that the tailwheel has better steering authority, and positioning the controls for the wind. Muscle memory dies hard, so remembering to keep the stick back while exiting the runway or taxiing can be difficult for tricycle gear pilots who typically release back pressure on the control wheel once aerodynamic braking is no longer necessary.

Three-point and wheel landings. The technique for landing a taildragger is similar to that of a tricycle-gear aircraft: “Remember, the key is just round out low, just as you would with a nosewheel airplane,” counseled the 6,300-hour instructor who flies a range of aircraft from the Super Decathlon to the Gulfstream IV. “You’re going to hold the airplane off the ground until you reach the three-point attitude, and when it settles, you get real active with your feet.

Three-point and wheel landings. The technique for landing a taildragger is similar to that of a tricycle-gear aircraft: “Remember, the key is just round out low, just as you would with a nosewheel airplane,” counseled the 6,300-hour instructor who flies a range of aircraft from the Super Decathlon to the Gulfstream IV. “You’re going to hold the airplane off the ground until you reach the three-point attitude, and when it settles, you get real active with your feet.

“At the moment the airplane touches down, the stick should still be coming back.”

For three-point landings, Rapp suggested trying to make the tail touch first, setting the pilot up for the three-point pitch attitude. If the mains touch first on a three-point attempt, the aircraft will bounce. “If the tailwheel is not on the ground, easing back on the elevator control may cause the airplane to become airborne again because the change in attitude will increase the angle of attack and produce enough lift for the airplane to fly,” according to the Airplane Flying Handbook.

With wheel landings, however, the goal is for the mains to touch first.

“Wheel landings are all about finesse,” Rapp said. Forcing the mains onto the runway and pushing the control stick forward to transfer the weight onto the wheels can result in a bounce or pilot-induced oscillations. Pilots must wait for the mains to touch before advancing the stick forward—and then, be patient while the aircraft decelerates before bringing the tail down.

After landing, the trick is to keep the aircraft under control during the rollout. The federal aviation regulations require currency landings in tailwheel aircraft to be to a full stop, day or night, for a reason: The challenge of landing one is bringing the aircraft to a stop without ground looping.

After a few hours—5G Aviation usually schedules six hours for transition training—of successfully taxiing the airplane and making dozens of takeoffs and landings under various conditions, most instructors will provide the coveted endorsement. Then it’s time to keep those skills sharp with some tailwheel flying adventures. Just remember to keep the aircraft aligned with the runway, stay active on the controls all the way to the tiedown spot or hangar, and keep that third wheel behind you where it belongs.

Email [email protected].

56%

of AOPA members have logged time in a tailwheel aircraft.

In a recent online poll, 28 percent of AOPA members said they have ground looped an aircraft.