Listen to this month’s “Never Again” story: A date with his girl. Download the mp3 file or download the iTunes podcast.

Hear this and other original “Never Again” stories as podcasts and download free audio files from our library.

I started flying lessons at age 16 at Dalton Airport in Flushing, Michigan. My instructor, Spike, was patient despite some breathtaking moments I provided in a Citabria 7EC. Unfortunately, my parents could not continue to afford the cost of the endeavor or the drive to Flushing.

So I worked out an agreement with a fixed-base operator at Flint’s Bishop Airport, near my home. I took care of aircraft for three hours of flight training per week. A Mooney Alon Ercoupe, 81F, was one that I flew a lot and I thought of her as something more than just an airplane. Each flight seemed more like a date.

By December 24, 1970, Boyce Reusegger, my new instructor, was eager to give me my checkride. Mother Nature cooperated by providing us with a perfect winter day. The skies were almost clear, the temperature was cold, the winds were predictable, and the landscape was covered with an ample amount of snow. I was eager and ready. My girl, 81F, looked just as ready for the challenge. There was something different about today, though. I sensed it so much so that it stopped me for a moment as I approached her. I’d always felt comfortable and connected with her when we were together, despite some of the rough handling I’d put her through. Boyce got my attention as he asked, “Are you ready?”

After an hour and a half, he began the final maneuver, a simulated engine out with a possible full-stop landing. He pulled the throttle to idle and said, “The engine failed.” The cockpit was quiet. When I completed the obligatory functions, Boyce said, “The engine failed to restart. You need to find an alternate landing site.”

I saw a small private airport next to a farmhouse within easy gliding distance at our 11 o’clock position. I explained my plan and he acknowledged with his approval. I had landed 81F at several grass strips and nontowered airports before. I had no reason to believe that this date would end any other way.

The windsock indicated a southerly flow down the private strip’s Runway 18. I also observed a large tree midfield to the left of the runway, two aircraft parked near the landing threshold, and a farm road ran about 100 to 200 feet north of the runway threshold.

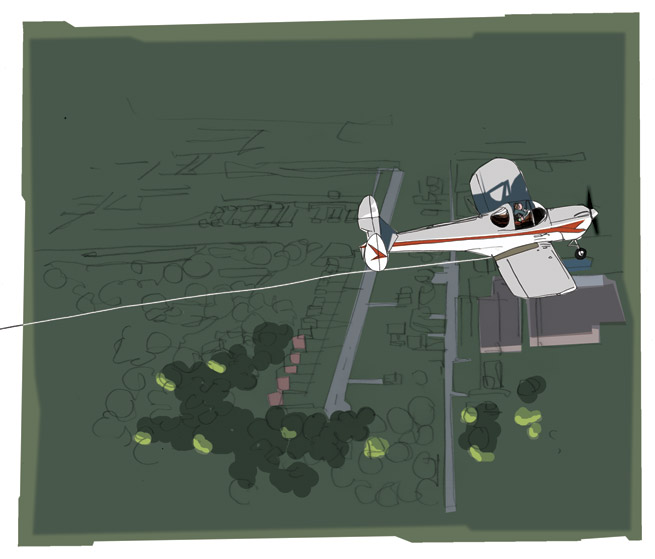

Everything was perfect, smooth, stabilized—and then I saw it. The faint image was like a flash before it disappeared. A thin, ominous wire appeared in front of us. We instantly pulled the yoke back into our chests while our hands pushed the throttle into the firewall. The silent cockpit was filled with the roar of a defiant engine as if she was desperate to avoid this fatal trap. I felt the airplane’s nosewheel skip over the top of the wire, followed by the screeching metal-on-metal noise of the cable quickly sawing across the lower surface of the wings. The sound was far worse than fingernails being dragged slowly across a chalkboard.

The wire caught on the main landing gear struts and caused the airplane to rapidly slow from a stabilized 80 knots to less than 60, and then zero. I waited for the inevitable, yet we remained airborne. A loud pop followed by two more pierced the cockpit. The metallic screeching became a loud, unmerciful grinding saw as the wire broke one strand at a time. The aircraft began to slide toward the end of the wire that refused to give up its stranglehold.

“I’ve got the airplane,” Boyce said. The remaining end of the wire snapped, and the airplane lunged forward as she fought to straighten herself. Once she did, she began to gain altitude.

The instruments that rely on the pitot system were not working. We had no idea what other damage had been done, and we didn’t know if the landing gear was safe. A quick look around outside revealed a line of cable extending from my side below the wing.

Landing back at Flint would be risky. We would have to use Runway 9 because the wind shifted and was now coming out of the east. The approach would require us to overfly high-tension lines along the final approach course. If the cable came into contact with the power lines, we would instantly become a Roman candle.

So we headed to Dalton Airport in hopes of finding some assistance. As we circled the airport, I saw a pilot run across the grassy field for the Citabria and launch. The pilot—Spike—reported that we had about 200 feet of cable trailing the aircraft. He told us we would not have any trouble with the power lines. Boyce accepted Spike’s judgment and advised the Flint control tower of our emergency. They cleared us to land at Flint and dispatched the airport fire and rescue unit.

While Boyce maneuvered my injured girl to the final approach course, Spike remained behind us offering reassuring comments. As we were rolling out, Boyce announced over the radio, “We have no brakes.” There seemed to be no solution. We were going to plow into a ditch if we did not stop in time. I felt my girl begin jerking from side to side. One of the firemen decided to run over the cable. That decision was the only thing that kept us from traveling through the fence.

Later, an FAA investigator told us we should have died several times that day and it was a miracle we hadn’t. We should have died when our aircraft made contact with the three-strand steel cable because we should have flipped over, and crashed inverted. There was no reasonable explanation for why the power line had broken as it did.

As for Spike, the investigator told us it was also a good thing that we had a friend who was as skilled as Spike. Why? We had not been able to see it, but Spike had used his expertise—and the left wing tip of his airplane—to keep the trailing cable above the high-tension lines until we cleared them. The investigator did not approve of Spike’s action because had he encountered turbulence, power loss, or any other problem, his aircraft’s propeller could have become entangled in the cable, causing both airplanes to crash.

What had I learned? Before doing this kind of maneuver, know the airport, the final approach course, and the movement area. I also learned something more important. No one could identify why the cable had broken the way it had. Boyce reminded me that sometimes the quality of the impossibilities in life are the best lessons. “This happened for a reason,” he said. “Live your life with a purpose.” He never liked to complicate things. His contribution to my perception of flying and the example of how to live a balanced life has continued with me all these years.

Keith Gunnell holds a private pilot certificate with multiengine rating and has logged more than 500 hours. He is a retired air traffic controller.

Jay scenario

How would you fly this flight? This scenario is available on the AOPA Jay from Redbird.