At 7 o’clock on a June morning—an hour when many teenagers on summer vacation still would be asleep—eight high school students form an attentive group around a Glasair Aviation employee. He’s about to give them their marching orders. “You’ll be drinking from a fire hose,” he tells them. While that phrase generally is reserved for type certificate training, it is just as appropriate here. The students will work long hours for the next two weeks riveting, drilling, and wiring.

This is a story about eight teens who came to Washington state to build airplanes. It’s also a story of how they got there, and how many facets of general aviation collaborated to demonstrate that aviation can be the jumping-off point for a rewarding career as well as a path to excitement.

One-on-one support

On an ordinary day at Glasair, one or two pilots might be up to their elbows in wires and cables, assembling a four-place Sportsman. Glasair offers a Two Weeks to Taxi program in which the buyer spends 14 days at its Customer Assembly Center (CAC) at Arlington Municipal Airport in Arlington, Washington. The end result: a rugged four-place Experimental taildragger with a sizable useful load (1,000 pounds) and an impressive cruise (135 knots at 75-percent power).

Glasair provides one-on-one technical support as well as a highly organized system in which tools, jigs, and parts for the metal and composite airplanes are laid out in advance. The company manufactures kits—some 1,200 of the aircraft are flying around the world—but Two Weeks to Taxi now represents most of its business. President Nigel Mott says builders have completed about 170 airplanes through the program. The key draw is that builders don’t have to spend years (sometimes decades) puttering about in their basements or hangars assembling an airplane that they may or may not complete in their lifetime.

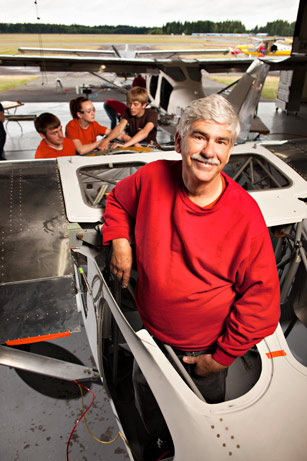

Today the CAC is swarming. Two pilots are tweaking a Sportsman that has already taxied—but there are also eight teenagers, two high school teachers, two principal builders, two chaperones, and several Glasair employees bustling around the hangar, working on two identical molded composite fuselages. In their wingless and engineless state, the gleaming white fuselages resemble cocoons. In two weeks, these aviation caterpillars will sprout wings and fly.

The six boys and two girls hail from Saline, Michigan, and Canby, Minnesota. They are here because the General Aviation Manufacturers Association and Build A Plane sponsored a contest in which 27 high school teams competed to design an airplane—their teams won first prize.

This was no paper-airplane competition. The students worked their way through a six-week Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math curriculum that required them not only to create a design but to test-fly it using the Fly To Learn program powered by X-Plane. Canby’s and Saline’s entries were so impressive that the judging panel of aeronautical engineers was challenged to choose one winner. Luckily, they didn’t have to.

Lycoming donated one kit; jointly owned by Build A Plane and GAMA, the airplane will sport a propeller and avionics donated by GAMA member companies Hartzell and Garmin. The second airplane will be flown by Jeppesen CEO Mark Van Tine, who is working alongside the teenagers as principal builder.

Working together

This isn’t the first time that Glasair and Build A Plane have collaborated on an airplane. In 2011, four teens and a principal builder assembled a Glasair Sportsman and showed it off at AirVenture that same year.

It is, however, the first time that Glasair has had to coordinate two simultaneous projects and eight pairs of hands (or 10, if you count the principal builders—or 12, if you throw in the two chaperones). That has been a challenge for Aircraft Production Manager Ben Rauk, who wants to make certain that the students get plenty of hands-on experience while ensuring that quality and safety protocols are met. “I’ve spread things out so that each student gets to have some part,” he explains.

A huge bulletin board on one wall of the CAC holds a numbered task list that breaks each build into “little bits and bites,” Rauk says. Tasks are signed off as they are completed; at the end of the build, this document will go to the FAA.

As they start the building process, Rauk challenges everyone to “put your thinking caps on—how does what [you’re] doing right now affect the airplane in its finished condition? Take a look at things very critically.”

Although the fuselages have been bonded and one of the airplanes is already on its landing gear, there’s much to do. Today’s agenda includes the aluminum vertical spar and putting skins on the wings. The students will learn how to rivet, and with 2,000 rivets per wing, they will get lots of practice.

Once they’re assigned to their jobs, the students settle in with a remarkable focus. Saline’s Julia Garner is installing a retainer clip for a flap cable. Before the day is through, she’ll put crimps in a fuel line and feed it through the wing, then install and wire the nav and landing lights. Canby’s Leah Schmitt and Brandon Stripling are mounting rudders and installing initial rudder cables, while others are mounting the main landing gear and tires.

Schmitt, Stripling, and team mates John Deslauriers and Wyatt Johansen came to the contest via an elective private pilot ground school taught by Dan Lutgen, himself a private pilot. All have flown in general aviation aircraft, and Deslauriers is a student pilot.

By contrast, Saline’s team—Garner, Kyle LaBombarde, Lee Luckhardt, and Aidan Muir—was enrolled in Ed Redies’ computer-assisted design/computer-aided manufacturing preengineering class. They had never tackled an aeronautical design. Before she arrived on the West Coast, Garner had never flown in any type of airplane, let alone a GA airplane. Luckhardt lives on a farm and is quite familiar with tools, but this is “my first experience with aircraft,” he says.

About midmorning, just before the first of two scheduled breaks, the CAC’s door rolls open, revealing a glimpse of gray sky that quickly clears off. The door remains open, and outside it becomes warmish, clear with scattered clouds. The Cascades, still with a hint of snow on their peaks in early summer, are visible from the Glasair parking lot.

Lutgen and Redies move from station to station, occasionally leaning in to help out. Redies says the process “looks like controlled chaos.” He speaks from experience; in 2011 he and his son built a Sportsman. He says things will progress rapidly over the first three or four days as the airplanes come together. “Then there will be three or four days when it seems like nothing is happening” as the builders tweak systems—then three to four days of rapid progress again, as each airplane is inspected and taxied.

Airplanes in the classroom

Build A Plane President Lyn Freeman says the “not too comforting” FAA statistics outlining a dwindling pilot population prompted him to form the nonprofit organization. Build A Plane works with the FAA and other aviation organizations such as GAMA and AOPA to promote aviation and aerospace education. It does this primarily by soliciting donated airplanes and placing them in schools. Kits, singles, and even the occasional twin find a place where they can be torn down or rebuilt. (Aircraft donations are tax-deductible, so if you have a hangar queen you can’t sell, Freeman would be very pleased to talk to you.)

Build A Plane has helped some 200 airplanes find their way to classrooms. “I thought if kids built automobiles [in auto shop], they might like to be able to build an airplane,” Freeman says. “Airplanes are wonderful teaching tools—they teach kids all kinds of things from satellites to upholstery.” In the process, students can get a unique exposure to aviation that might spark some interest. The hope, of course, is that these students will follow that interest along a path to a pilot certificate or a career in aerospace/aviation.

If they can get that kind of hands-on experience in a classroom, why bring them to the Pacific Northwest? According to GAMA President and CEO Pete Bunce, the collaboration was an opportunity to make STEM even more tangible by showing students how an airplane goes from a concept on paper to an aerodynamic design. GAMA member companies were keen to support it, he said, providing equipment for the airplanes as well as sponsorship for the two-week trip.

In the air

As the airplanes move closer to their date with an FAA inspector, the students continue to work at an impressive pace. Glasair’s Rauk provides a status report as part of each morning briefing, and progress generally is ahead of schedule or right where it should be.

During an afternoon when the sun makes an appearance, Glasair Director of Marketing and Sales Chris Strachan plucks first one, then another student from the CAC; installs him or her into the right seat of a red-and-black Sportsman with fat tundra tires; and taxies out to the runway. The Canby students are over the moon to be in the air; John Deslauriers brought his logbook for just such an opportunity. Stripling says he is going to pursue a private pilot certificate, and adds, “Flying is really a joy for me. It gives you that little bit of adrenaline rush while showing you how great the land is. You can climb a tall building, but you can only see so far.”

Flying works its magic on Saline’s students, too. Aidan Muir’s father, Dustan, pulls out a cellphone to show a self-portrait of his son taken in the Sportsman; Aidan’s smile is as wide as it can be. Dustan has been helping out with the build while fielding texts from home about Aidan’s college ice hockey prospects. The six-foot, three-inch forward appears to be headed for Western Michigan University, and says he may investigate that school’s aviation program.

On schedule

Thanks to the efficiency of the Two Weeks to Taxi program, the Build A Plane winners deliver the two Glasairs on schedule. The first airplane taxies on a drizzly afternoon that does not dampen the students’ spirits. They express surprise and satisfaction that their hard work paid off in such a relatively short amount of time, but that is not the end of the story—nor is it the last time they will see the Glasairs.

At AirVenture 2013 in Oshkosh, seven of the eight students have a happy reunion with the airplanes, which are parked in front of the GAMA/Build A Plane exhibit. All of them believe building an airplane was life-changing in a way that few other high school experiences can match. “It’s not every day you can say you built an airplane,” Garner says.

Schmitt got a chance to fly right seat in Van Tine’s Glasair, when he stopped in Minnesota on his way to Oshkosh. “It was amazing to be flying in the airplane I built,” Schmitt said. “A year ago, I never thought this would happen.”

Email [email protected]