What seems like a complicated device is actually quite simple when you compare its operation to your own body. An autopilot is essentially a mechanical version of you, the pilot. Your eyes see a bank or pitch change. They send a signal to your brain, which processes the change then sends another signal to your muscle, which makes a control input. That muscle receives feedback, and the whole process forms a loop.

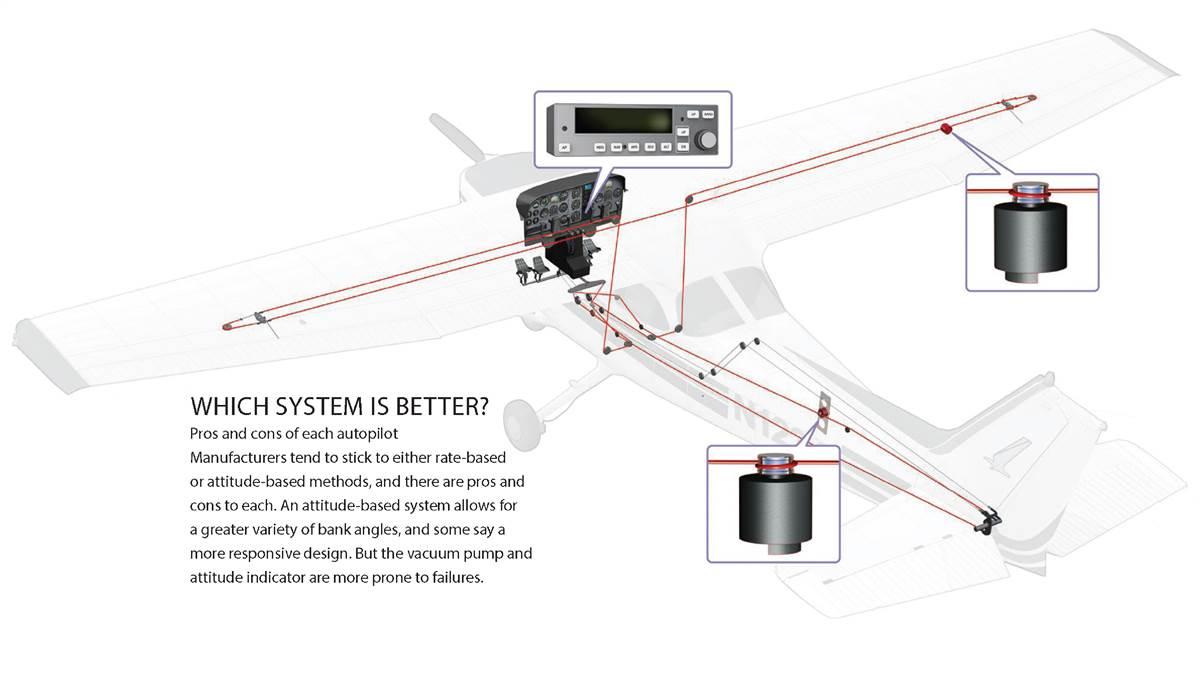

Autopilots take their cues from either the attitude indicator (so-called attitude-based) or turn coordinator (so-called rate-based). Sensors in the instruments send a signal to a processor that determines the necessary pitch or roll input. It then sends an electrical signal to a servo, which is nothing more than a motor that actuates the necessary control.

To avoid overcontrolling, a sensor in the servo sends another signal back to the processor, completing a feedback loop that ensures the controls don’t go too far afield in an effort to correct a pitch or bank change.

As autopilots get more sophisticated, they can control heading, intercept and track a course, climb or descend at a specific rate, capture altitudes out of a climb or descent, and even anticipate turns with GPS.