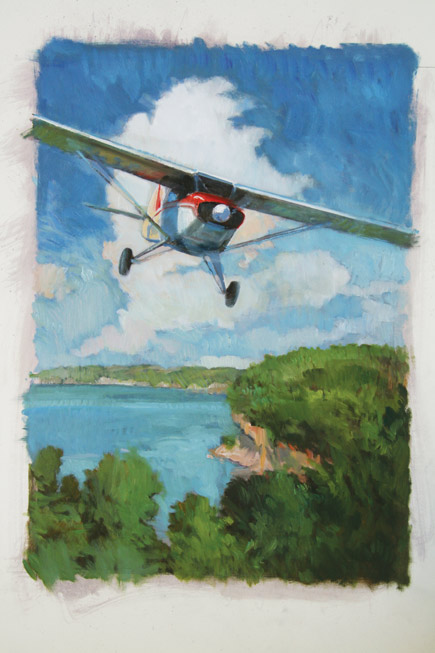

New perspective

An airplane renews a pilot’s passion

I lucked into my first airplane ride in a Cherokee 140 when I was 15 years old, and for the next two years, all my lawn-mowing money went straight into the cash register of the local FBO.

I lucked into my first airplane ride in a Cherokee 140 when I was 15 years old, and for the next two years, all my lawn-mowing money went straight into the cash register of the local FBO.

In 1977, 10 hours of dual in a Cessna 150 with fuel could be had for $210. Those two years until I reached age 17 and could become a private pilot seemed to take forever. But during that time I went to ground school with my dad, and fell into the rhythm of my new economic reality: Mow three lawns, fly one hour.

I barely managed to stay current during college, but after entering the U.S. Air Force my flight economic model reversed. I added ratings and flight time and actually got paid to do it. With my logbook padded by lots of multiengine jet hours, I landed a major airline job in the 1990s and started pushing the career autopilot button. Thirty-five years had passed since that first Cherokee ride, along with more than 17,000 hours spent mostly at cruise, transoceanic crossings, warzone entries followed thankfully by warzone exits, and instrument approaches in near-zero visibility. Happily, my number of takeoffs was still equal to my number of landings. But as I accomplished my career goals, I realized I had lost touch with the simple, joyful aspects of flying that first attracted me as a teen. I also realized that I wanted to pass on that love of flying and see if it might catch on with any of my five kids.

At EAA AirVenture in Oshkosh last year, with my brother-in-law Mike, my only goal was to buy a T-shirt. After two days of renewing old acquaintances and bumming around the flight line, Mike spotted a 1963 Piper Colt with a shiny red finish and a “For Sale” sign. While the rest of the crowd was entranced with the airshow, I chatted with the Colt owner, an airline mechanic named Greg.

The Colt had been born a year after me, and it served as a trainer for 20 years before finally ending up in the hands of an A&P. It would take 25 more years for that individual to strip the airplane to the tubular frame, meticulously stretch the new fabric, zero-time the Lycoming O-235, update the upholstery and headliner, add toe brakes, comply with the airworthiness directives, and complete a supplemental type certificate tailwheel conversion. Greg and his partner, Gary, became co-owners during the rebuild.

"Must have taken a lot of hours to make all those improvements,” I said to Greg.

The mechanic looked at me and, with great patience, replied, “You have no idea.”

The engine log book showed just 2.3 hours since overhaul.

Then, like my six-year-old daughter Nikki’s impulse to buy a candy bar in the checkout line, I got the bug. I quickly snapped a cellphone picture of the airplane and sent it to my wife, Beth, with a short note. “It costs about as much as the used Suburban we bought last year. What do you think?” Beth, a lifelong St. Louis Cardinals fan, answered quickly. “As long as we call it Redbird.”

Immediately, I felt like I was 15 again—excited but clueless. I took Greg’s business card and promised to call, then spent my remaining time at Oshkosh learning as much as I could. The wealth of general aviation knowledge made me realize how little I really knew about current GA operations and aircraft ownership. I hadn’t read a VFR sectional chart in 20 years, and I soon discovered that they could be loaded on an iPad. My weather briefings at work are prepared neatly by dispatchers for preflight review, and in the GA world I learned that I no longer had to know the local FSS phone number to get a briefing. My head began swirling with questions about fabric maintenance, annual inspections, advantages of alternators over generators, GPS receivers, transponder requirements, engine break-in procedures, and ADS-B.

My single-engine flying experience as a teen had been buried under decades of type ratings, transport jets, and Level-D flight simulation. GA flying would be so different, and I had a lot of catching up to do. This was not going to be like buying a used car. I had to start from scratch.

At home in Parker, Colorado, I delved into the enormous amount of information on buying airplanes through the AOPA member website. I also found hangar talk with wiser GA pilots invaluable. With a combination of both, I prepared an offer contingent on an aircraft logbook review and a prepurchase flight and inspection. Two weeks after first seeing Redbird, I traded a down payment for the keys. Much to my relief, my employer announced a new pilot contract on the very same day.

Greg and Gary replaced the stock generator with an alternator, upgraded the wiring, and installed a used Garmin 496. I felt very good about the airplane when the two professionals handed it over. With the promise of VFR skies and a couple of days off, I gladly assumed the right seat for the two-day trip home from Illinois. With my meager tailwheel experience literally decades old, I offered the left seat to a GA pilot named Ted, who agreed to be pilot in command.

On the first day, I picked the brain of my flying companion about everything from airspace to leaning techniques while he questioned me about airline flying. As we cruised at minimum safe VFR altitudes over the Midwestern landscape, my internal E6B woke up and started figuring wind drift, fuel burn, and dead reckoning. A friend had graciously arranged an overnight hangar in Larchwood, Iowa, near my brother-in-law Mike’s home, where more than 20 friends and relatives turned out to see my new toy. The joy of flying was coming back.

Day two brought strong headwinds, and our groundspeed fell to just 77 knots—about half the rotation speed of the airliner I fly. I wasn’t in a hurry, though. After a fuel stop in Yankton, South Dakota, we continued on. Soon we were over the Lewis and Clark Reservoir, a familiar landmark I was accustomed to seeing from seven miles high—but now only the clouds were high overhead. My smile came back wider than ever.

At home in Colorado, I’ve flown with each of my kids and explored the magnificent Front Range from the air. Owning and flying this simple airplane has given us a new perspective and fresh insights on the place we live—and the joy that is nowhere else to be found except in the lower altitudes. Aviation, which for so long had been a purely professional pursuit, is now a shared activity that brings our whole family together. Nikki, our youngest, seems the most enthusiastic and adventurous, and asks to go whenever the windsock looks tranquil.

Redbird has only been a part of our family for a few months, but I feel profoundly different as an aviator. For the first time in a very long time, the challenge, wonder, and pure enjoyment are back.

Bob McSpadden flies for a major U.S. airline and lives on a residential airpark near Denver.

Illustration by Francis Livingston